Cost-Based Payment

Most small rural hospitals receive “cost-based payment” for services to Original Medicare beneficiaries. Most of the smallest rural hospitals are designated as “Critical Access Hospitals,” which enables them to receive payments for patients with Original Medicare based on the actual cost of the hospital’s services instead of receiving standard Medicare fees. (Medicare Advantage plans are not required to pay Critical Access Hospitals using cost-based payments or standard Medicare fees.) Rural Health Clinics operated by small rural hospitals are also eligible for cost-based payment from Medicare.

Payments under Medicare’s cost-based payment system are less than the actual costs of delivering services. Not all services are eligible for cost-based payment, and not all of the costs of services are included when payments are calculated. In addition, although Critical Access Hospitals were originally paid 101% of their eligible costs and Rural Health Clinics were paid 100% of their eligible costs, federal sequestration rules have reduced payments to only 99% and 98% of eligible costs since 2013. These reductions were suspended during the pandemic, but went back into effect in 2022.

Medicare beneficiaries have to pay more for services at Critical Access Hospitals than at other hospitals of similar size. Medicare’s cost-based payments to a Critical Access Hospital (CAH) will generally be higher than Medicare fee-for-service payments, which is financially beneficial to the hospital. However, Medicare rules require that the cost-sharing amounts paid by beneficiaries increase even more than the increase in Medicare payments, which makes services less affordable for patients.

Critical Access Hospital status does not and cannot prevent rural hospitals from closing. One-third of the rural hospital closures over the past decade have been Critical Access Hospitals. Although Critical Access Hospitals generally lose less money on Medicare patients than they would under standard Medicare fee-for-service payments, Critical Access Hospital status does nothing to prevent losses on patients with other kinds of insurance or on uninsured patients.

Cost-Based Payment as an Alternative to Fees for Services

The History of Cost-Based Payment for Rural Hospitals in Medicare

The financial problems small rural hospitals experience when they are paid the same amounts as larger hospitals are not new; they have existed for more than three decades. The primary approach used to date to address the problems has been to pay small, isolated hospitals using “cost-based payment” rather than standard fees for each service.

When the Medicare program was first created in 1965, it paid all hospitals based on their “reasonable costs” of delivering services, and most private insurance plans paid the same way. This enabled small rural hospitals to receive higher payments to cover higher costs. However, because of the rapid growth in hospital spending that occurred under this system, Congress created the Inpatient Prospective Payment System (IPPS) in 1983 in an effort to control the cost of inpatient care.1 Under IPPS, hospitals began receiving predetermined fees (case rates) for inpatient admissions based on the health conditions treated and the procedures performed, rather than the costs that were actually incurred.2

Although the IPPS was generally viewed as successful in controlling Medicare spending on hospitals without harming patients, there were serious concerns about the negative impact the IPPS system was having on small rural hospitals. By the fourth year of the IPPS, most rural hospitals were losing money on their Medicare patients, while most urban hospitals were making profits on them.3 From 1985-1988, 140 rural hospitals had closed, most of which had less than 50 beds.4 A study by the U.S. General Accounting Office found that one-third of the smallest rural hospitals that closed lost more money on Medicare patients than on other patients.5

To address this problem, Congress created the Medicare Rural Hospital Flexibility Program6 in 1997. States were permitted to designate rural hospitals as “Critical Access Hospitals” if they met certain criteria, and Medicare was required to pay Critical Access Hospitals (CAHs) for both their inpatient and outpatient services based on the reasonable cost of providing those services.

The Impact of Cost-Based Payment on Critical Access Hospitals

Today, the majority of rural hospitals are designated as Critical Access Hospitals, and 80% of the smallest rural hospitals (those with less than $20 million in total expenses) are Critical Access Hospitals. Although losses on patient services are generally smaller at Critical Access Hospitals than other small rural hospitals because of the smaller losses on Medicare patients, the majority of Critical Access Hospitals and other types of small rural hospitals lose money on patient services and cannot remain open without other sources of funding.

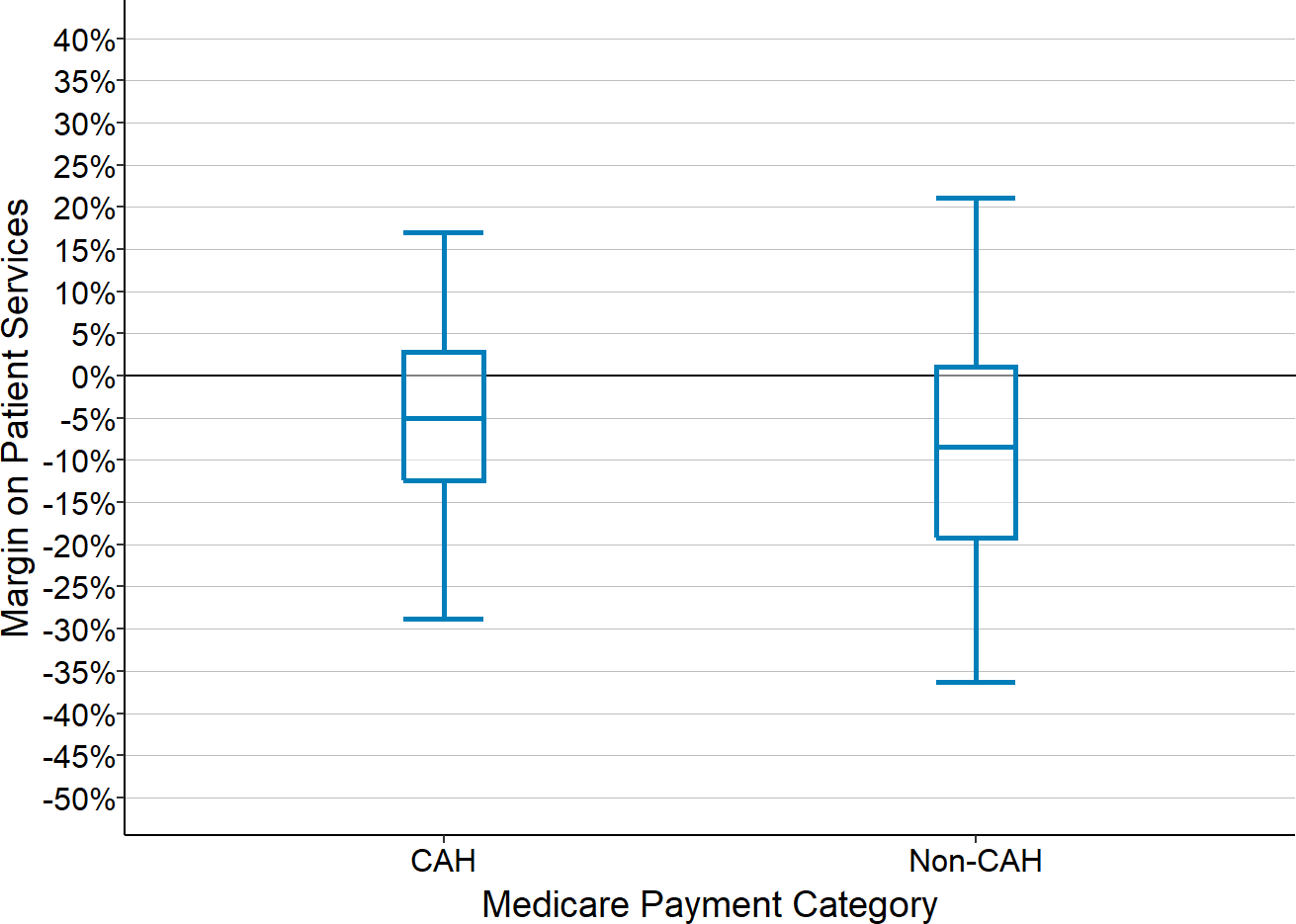

Figure 1

Patient Service Margins at Critical Access Hospitals

and Other Small Rural Hospitals

Financial margin on patient services for rural hospitals with <$45 million in total expenses. Values are the medians for each hospital during the most recent three years available.

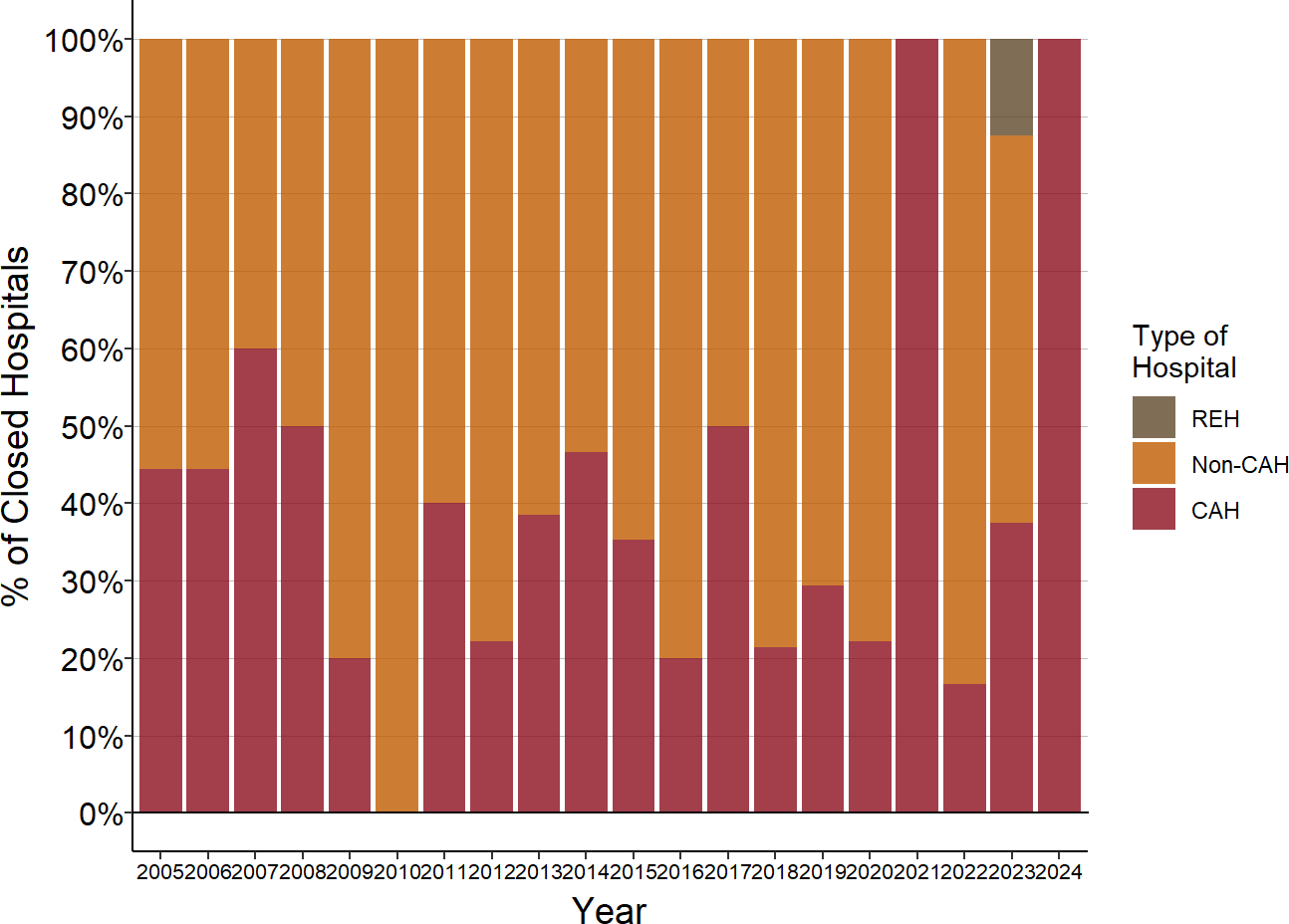

Moreover, Critical Access Hospital status has not prevented rural hospitals from closing. One-third of the rural hospital closures over the past decade have been Critical Access Hospitals, with higher percentages in some years.

Figure 2

Closures of Critical Access Hospitals

and Other Rural Hospitals

Source: Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research and CMS Data

An obvious question is whether the failure of Critical Access Hospital status to prevent financial problems and closures is because of problems with the cost-based payment methodology used or because other payers do not use it.

How Cost-Based Payment for Rural Hospitals Works

Why Cost-Based Payments Do Not Cover All Costs

People who do not understand the complexities of Medicare’s cost-based payment system often inappropriately describe it as “cost-plus” payment, assuming that Medicare simply reimburses a rural hospital for any costs it incurs. However, the reality is very different. The amount of cost-based payment that a hospital receives under this system will almost always fall short of the hospital’s total costs because of four components of the payment methodology:

Not all services and costs are eligible for cost-based payment. Not every service the hospital delivers is eligible for cost-based payment. For example, if the hospital operates an ambulance service, the hospital receives standard Medicare fees for that service, not a cost-based payment. Moreover, even if a service is eligible for cost-based payment, not every type of cost incurred in delivering the service is eligible. For example, the time an ED physician spends in the ED waiting for patients to arrive is considered an eligible cost, but the time the physician spends with ED patients is not. (The hospital receives a standard Medicare fee for each physician visit to pay for the time spent with patients, and this may or may not be more than the portion of the physician’s compensation that is allocated to patient visits.)

Only the portion of the total eligible cost that is attributable to Medicare patients is eligible for cost-based payment. Within each service line that is eligible for cost-based payment, Medicare determines the proportion of the eligible costs that is attributable to Medicare patients. Different formulas are used to determine this fraction for different types of services, but the basic concept is that if Medicare beneficiaries received x% of the services delivered in a service line, then Medicare pays for x% of the eligible costs of the service line. Medicare does not pay for any of the costs associated with other patients, regardless of whether they are uninsured or whether the payments from their health plans are less than the cost of services.7

Medicare’s payment is reduced by the patient’s cost-sharing amount. In the Medicare program, every beneficiary has to meet a deductible before Medicare will pay for a service, and beneficiaries are also required to pay co-insurance on all outpatient services. The total amount of cost-based payment the hospital is eligible to receive is reduced by the required amount of cost-sharing in order to determine the amount Medicare pays. The hospital must then get the balance from the patient. Because the cost of services at small rural hospitals is higher than what Medicare typically pays for services, the cost-sharing amount for the beneficiaries is also higher. Although many Medicare beneficiaries have supplemental insurance plans that pay for their required cost-sharing, most do not. If the patient cannot pay the cost-sharing, Medicare will pay 65% of the cost of the patient’s bad debt, but not the full amount.

Sequestration reduces the Medicare payment. The federal statute that created the cost-based payment system specifies that the total Medicare payment (including the patient cost-sharing amount) will be 101% of the eligible cost. However, under sequestration rules, all Medicare payments are reduced by 2%8, so in actuality, the hospital will only receive about 99% of its eligible costs.9

Specific Issues with Cost-Based Payments for Outpatient and Ancillary Services

For ED visits and for ancillary services such as lab tests and imaging studies (including ancillary services delivered to patients during an inpatient stay), the fraction of the eligible cost in the service line that is attributable to Medicare patients is determined based on the percentage of the hospital’s total charges for the services that were billed to Medicare beneficiaries. For example, if 50% of the hospital’s total charges for lab tests were billed to Medicare beneficiaries, then Medicare pays for 50% of the eligible costs of the laboratory.

For outpatient services such as ED visits and ancillary services, a Medicare beneficiary is generally responsible for paying co-insurance equal to 20% of the fee that Medicare pays for an outpatient service, and then Medicare pays the remainder (i.e., 80%) to the hospital. At a rural hospital that is designated as a Critical Access Hospital, beneficiaries are also required to pay co-insurance for these services, but the co-insurance amount is calculated differently. Medicare beneficiaries are responsible for paying 20% of the amount the Critical Access Hospital charges for each service they receive, not 20% of the amount that Medicare pays. This co-insurance amount is deducted from the cost-based amount calculated in the second step, and Medicare is then responsible for paying the balance to the hospital. Since hospitals ordinarily will charge significantly more for an outpatient service than what it costs to deliver the service (since the hospital will be required to “discount” the charge by private insurance plans), this means that Medicare beneficiaries will pay more than 20% of the cost of the service, and Medicare will pay less than 80%.

Specific Issues with Cost-Based Payment for Inpatient Services

There are two differences in the way the cost-based payment for nursing care on an inpatient unit is determined:

The estimated cost of long-term nursing care in swing beds is excluded. Since acute care and inpatient rehabilitation are services covered by Medicare but long-term nursing care is not, the cost of providing long-term nursing care in swing beds has to be excluded from the total cost of the inpatient unit before calculating Medicare’s share of the cost. However, it is impossible to precisely determine a small hospital’s cost for delivering long-term nursing care in swing beds because the long-term nursing care patients are generally on the same inpatient unit at the same time as patients who are receiving acute care or inpatient rehabilitation, and all of the patients are receiving care from the same nurses and nursing assistants. To address this, Medicare estimates the cost of the long-term nursing care using the per diem amount that the state Medicaid program pays for long-term nursing care. For example, if the state Medicaid program pays $180 per day for long-term care in a nursing facility, and if the hospital provided 1,000 days of long-term care in its swing beds during the year, then CMS will subtract $180,000 from the total cost of the inpatient unit in order to determine the cost of inpatient acute and rehabilitative care.

Medicare’s share of costs is based on days of service rather than charges. Medicare’s share of the estimated inpatient acute and rehabilitative cost is based on the number of days of inpatient care Medicare beneficiaries receive rather than the hospital’s charges for those days. The estimated cost of inpatient acute and rehabilitative care that was determined in the previous step is divided by the total number of days of inpatient acute and rehabilitative care provided on the inpatient unit to estimate the cost per day for inpatient acute and rehabilitative care. That estimated cost per day is then multiplied by the number of days of inpatient acute and rehabilitative care received by Medicare beneficiaries to determine the Medicare share of the cost. Even if the Medicare beneficiaries are receiving higher-intensity care than other patients, unless the hospital has a separate Intensive Care Unit, the hospital will receive the same payment from Medicare for every day of patient care. There is also no distinction made between how many patients received acute care vs. rehabilitative care in swing beds.

Using the Medicaid payment rate to estimate the cost of long-term nursing care in swing beds rather than the amount the hospital charges for that care means that if the Medicaid payment rate is below the actual average cost of providing long-term nursing care, the Medicare program is actually paying for a portion of the cost of long-term nursing care in a Critical Access Hospital. The subsidy is larger in states that have lower Medicaid payment rates. This may be the only way that residents of a small rural community can have access to long-term care services in the community, since it may be impossible for either the hospital or any other entity to operate a Skilled Nursing Facility with the standard amounts paid by Medicare for rehabilitation services and the standard payments from Medicaid for long-term services. However, this Medicare subsidy is only available if there is at least one Medicare beneficiary receiving acute inpatient care in the hospital. If the hospital were to no longer offer inpatient acute care, it would lose this subsidy, and the community would likely also lose the ability to support long-term care services.

Specific Issues with Cost-Based Payment for Clinic and Rural Health Clinic Services

If a Critical Access Hospital operates a clinic that is not designated as a Rural Health Clinic, even if the clinic is providing primary care services, Medicare will not provide cost-based payment for the physicians, nurse practitioners, or physician assistants who work in the clinic, it will only provide cost-based payment for other costs such as nurses or equipment. The cost of the compensation paid to clinicians has to be supported through standard Medicare fees.

However, if the clinic is designated as a Rural Health Clinic, the hospital can receive cost-based payment for the clinicians as well as other costs.10 In fact, any rural hospital with less than 50 beds can receive cost-based payment for Rural Health Clinics.11

The process for determining the Medicare payment for a Rural Health Clinic is similar to what is used for other services at Critical Access Hospitals, but there are several important differences:

As noted above, the salaries paid to physicians and other clinicians are considered eligible costs at an RHC, including all of the time they spend with patients.

At an RHC, the portion of costs attributable to Medicare beneficiaries is based on the percentage of total clinic visits they make, rather than on the percentage of total clinic charges, i.e., if Medicare beneficiaries make 50% of the visits to the clinic, then Medicare will generally pay 50% of the cost of operating the clinic, regardless of whether the Medicare patients spent more time in the clinic during their visits or received more services during their visits than other patients.

Medicare reduces the share of the RHC’s cost that it supports if the clinicians fail to meet productivity standards established by Medicare. The formula for determining the Medicare share of cost for RHC visits has three steps:

- the total actual number of visits at the RHC is compared to the total number of visits there would have been if each FTE physician had 4,200 visits and each FTE nurse practitioner or physician assistant had 2,100 visits. If the actual number of visits is lower than the minimum number required by the productivity standards, the minimum number of visits is used for calculating costs rather than the actual number of visits. For example, if the RHC had 1 FTE physician and 1 FTE NP who saw a total 5,000 patients during the year, that would be below the productivity standard of 6,300 visits (4,200 visits per FTE physician + 2,100 visits per FTE NP), so the clinic would be treated as though it had 6,300 visits rather than 5,000.

- the total eligible cost at the RHC is divided by the total number of visits determined in the previous step in order to calculate an adjusted cost per visit. In the example above, the adjusted cost per visit would be lower than the actual average cost per visit because the total cost is divided by 6,300 visits rather than the actual number of 5,000.

- the adjusted cost per visit calculated in the previous step is multiplied by the actual number of visits made by Medicare beneficiaries to determine the total amount of cost that Medicare supports.

At an RHC, the full “allowed amount” from Medicare is based on 100% of the eligible cost, not 101% as with other services at a Critical Access Hospital.

The Medicare beneficiary is responsible for paying co-insurance equal to 20% of the clinic’s charge for the visit, but unlike Critical Access Hospital services, the beneficiary’s actual co-insurance payment is not deducted from the Medicare payment. Instead, Medicare pays 80% of what it has determined as the Medicare share of cost, regardless of whether the patient co-insurance payments are higher or lower than 20% of that amount.

The actual Medicare payment is then reduced by 2% because of sequestration, so the Medicare share of the payment is less than 80% of the actual costs.

Examples of How Cost-Based Payment Affects Hospital Margins

The implications of the many complex details in Medicare’s cost-based payment methodology can be seen more clearly by examining how cost-based payment would support the services in the hypothetical hospitals described in The Cost of Rural Hospital Services.

Cost-Based Payment for Emergency Department Services

The table below shows the revenues and costs for an Emergency Department at a hypothetical Critical Access Hospital that has 5,000 total visits per year. It is staffed identically to the example that is shown in , so it has a total cost of $2.7 million and an average cost per visit of $540. In addition, at this hypothetical ED, it is assumed that:

50% of the patients are Medicare beneficiaries (who are in the “Original Medicare” program, not a Medicare Advantage plan), 5% are uninsured, and the remainder have an insurance plan (Medicaid, Medicare Advantage, or commercial insurance) that pays fees for services.

For each visit to the ED, the hospital charges the patient a total of $850 ($750 for the hospital services and $100 for the physician’s time), which is 50% more than the average cost of a visit.

Insurance plans other than Medicare are assumed to pay an average of $400 for a visit ($240 for the facility fee and $160 for the physician). This is less than 50% of the amount the hospital charges, but the hospital has to accept this as payment in full if it accepts the patients’ insurance.

The amounts that Medicare pays the hospital are:

- a $178 physician fee for each visit.12

- a cost-based payment for the hospital’s average cost per visit, which includes the cost of employing the physicians, except for the time the ED physicians actually spend with patients. In this hypothetical ED, it is assumed that the ED physicians spend an average of 30 minutes with each patient.

Uninsured patients are unable to pay anything for a visit.

Figure 3

Revenue and Costs for the Emergency Department

at a Hypothetical Critical Access Hospital

| Visits | Charges | % of Total |

Payment Per Service |

Amount | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Payments | |||||

| Medicare ED Visits Facility Cost | 2,500 | $1,875,000 | 50% | $466 | $1,164,000 |

| Other Payers ED Visits Facility Fee | 2,250 | $1,687,500 | 45% | $240 | $540,000 |

| Uninsured ED Visits Facility Fee | 250 | $187,500 | 5% | $0 | $0 |

| Subtotal ED Visits Facility Payments | 5,000 | $3,750,000 | 100% | $341 | $1,704,000 |

| Medicare ED Visits Physician Fee | 2,500 | $250,000 | 50% | $178 | $445,000 |

| Other Payers ED Visits Physician Fee | 2,250 | $225,000 | 45% | $160 | $360,000 |

| Uninsured ED Visits Physician Fee | 250 | $25,000 | 5% | $0 | $0 |

| Subtotal ED Visits Physician Payments | 5,000 | $500,000 | 100% | $161 | $805,000 |

| Total Revenue | 5,000 | $4,250,000 | $502 | $2,510,000 | |

| Cost | |||||

| Facility Cost | $2,338,000 | ||||

| Cost of Clinician Patient Time | $360,000 | ||||

| Total Cost | $2,698,000 | ||||

| Margin | |||||

| Margin | ($188,000) | ||||

| Pct Margin | −7.0% | ||||

The result is a loss of nearly $190,000 for the hospital. Even though the ED is receiving cost-based payment from Medicare, the fees paid by other payers are below the average cost per visit, and so total revenues fall 7% short of the amount needed to pay for the total cost of the ED.

It is virtually impossible for the hospital to eliminate this loss by trying to reduce the cost in the ED. The ED has the bare minimum staffing to manage patients that arrive every 2 hours on average, so it cannot reduce staff without negatively affecting the quality of care. Even if the hospital was able to reassign a portion of the overhead costs to other departments, the payment from Medicare would decrease when the total cost is reduced, and the hospital would still lose money on the operation of the ED.

The table below shows an ED with many more visits – 12,500 per year instead of 5,000. The cost of operating this ED will be somewhat higher; it is assumed to be staffed the same as the example of an ED with 12,500 visits shown in , so it has a total cost of $3.2 million. Because of the much larger number of visits, its average cost per visit is only $257 – less than half as much as the smaller ED. As a result, the hospital might only charge $500 per visit ($400 for the hospital services and $100 for the physician services). Even if the hospital is only paid $185 by insurance plans other than Medicare ($120 for the facility fee and $65 for the physician), which is less than half as much as in the previous example, the hospital will have a small positive margin on the ED.

Figure 4

Revenue and Costs for an Emergency Department

at a Critical Access Hospital with a Larger Number of Visits

| Visits | Charges | % of Total |

Payment Per Service |

Amount | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Payments | |||||

| Medicare ED Visits Facility Cost | 6,250 | $2,500,000 | 50% | $185 | $1,154,000 |

| Other Payers ED Visits Facility Fee | 5,625 | $2,250,000 | 45% | $120 | $675,000 |

| Uninsured ED Visits Facility Fee | 625 | $250,000 | 5% | $0 | $0 |

| Subtotal ED Visits Facility Payments | 12,500 | $5,000,000 | 100% | $146 | $1,829,000 |

| Medicare ED Visits Physician Fee | 6,250 | $625,000 | 50% | $178 | $1,113,000 |

| Other Payers ED Visits Physician Fee | 5,625 | $562,500 | 45% | $65 | $366,000 |

| Uninsured ED Visits Physician Fee | 625 | $62,500 | 5% | $0 | $0 |

| Subtotal ED Visits Physician Payments | 12,500 | $1,250,000 | 100% | $118 | $1,479,000 |

| Total Revenue | 12,500 | $6,250,000 | $265 | $3,308,000 | |

| Cost | |||||

| Facility Cost | $2,313,000 | ||||

| Cost of Clinician Patient Time | $900,000 | ||||

| Total Cost | $3,213,000 | ||||

| Margin | |||||

| Margin | $96,000 | ||||

| Pct Margin | 3.0% | ||||

Cost-based payment from Medicare does not prevent the smaller ED from having losses, and the profitability of the larger ED is primarily due to the higher volume of visits, not because of cost-based payments.13

Cost-Based Payment for Inpatient Care

The table below shows the revenues and costs for an inpatient unit at a hypothetical Critical Access Hospital. The hospital has an average daily census of 9 patients, consisting of an average of 1.5 acute patients per day, 1.5 inpatient rehabilitation patients in swing beds each day, and 6 patients per day receiving long-term nursing care in a swing bed. It is staffed identically to the example that was shown in , so it has a total cost of $3.2 million. In addition, it is assumed that:

50% of the patients receiving acute care or inpatient rehabilitation are Medicare beneficiaries (who are in the “Original Medicare” program, not a Medicare Advantage plan). The remainder have health insurance plans (Medicaid, Medicare Advantage, or commercial insurance) that pay an average of $3,000 per day for acute care and $800 per day for inpatient rehabilitation.

50% of the patients receiving long-term nursing care in swing beds are Medicaid patients, and the Medicaid program pays $180 per day for this care. The remainder are private-pay patients and the hospital charges them $300 per day.

Figure 5

Revenue and Costs for the Inpatient Unit

at a Hypothetical Critical Access Hospital

| Days | Charges | % of Total |

Payment Per Service |

Amount | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Payments | |||||

| Medicare Acute Days Inpatient Cost | 274 | $684,375 | 50% | $2,481 | $679,000 |

| Other Payers Acute Days Inpatient Fee | 274 | $684,375 | 50% | $3,000 | $821,000 |

| Subtotal Acute Days Payments | 548 | $1,368,750 | 100% | $2,741 | $1,501,000 |

| Medicare Swing SNF Days Inpatient Cost | 274 | $205,313 | 50% | $2,481 | $679,000 |

| Other Payers Swing SNF Days Inpatient Fee | 274 | $205,313 | 50% | $800 | $219,000 |

| Subtotal Swing SNF Days Payments | 548 | $410,625 | 100% | $1,641 | $898,000 |

| Medicaid Swing NF Days Inpatient Fee | 1,095 | $547,500 | 50% | $180 | $197,000 |

| Private Payers Swing NF Days Inpatient Fee | 1,095 | $547,500 | 50% | $300 | $328,000 |

| Subtotal Swing NF Days Payments | 2,190 | $1,095,000 | 100% | $240 | $526,000 |

| Total Revenue | 3,285 | $2,874,375 | $890 | $2,924,000 | |

| Cost | |||||

| Total Cost | $3,183,000 | ||||

| Margin | |||||

| Margin | ($259,000) | ||||

| Pct Margin | −8.1% | ||||

As shown in the table, the result is a loss of over $250,000 for the hospital. Even though Medicare is paying over $2,400 per day for both acute and inpatient rehabilitation, which is more than double the average cost per day on the inpatient unit, most of the patients are not Medicare patients, and the revenues from the other payers fall far short of the amount needed to cover the cost of the inpatient unit.

It is virtually impossible for the hospital to eliminate this loss by reducing costs in the inpatient unit. The unit has the bare minimum staffing to safely provide care for an average of 9 patients per day, so it cannot reduce staff. Even if the hospital reduced its overhead costs or reassigned a portion of the overhead cost to other departments, the hospital could still lose money on the operation of the inpatient unit and/or lose money hospital-wide.14

It might appear that the loss is primarily due to the low payments from Medicaid for the long-term nursing patients on swing beds. However, the hospital has a lower average cost per day than it otherwise would because of the large number of patients receiving long-term nursing care, and under the formula used to determine the Medicare share of costs, the hospital gets higher Medicare payments because of those patients.

The table below shows what would happen if the hospital had no long-term nursing patients at all and solely provided care for the acute and inpatient rehabilitation patients. Even though the hospital’s average daily census would drop by 2/3 without the nursing patients, the hospital’s staffing would not decrease proportionally, since the hospital still has to have two nurses on the unit at all times. (The staffing level is the same as what was shown in for a hospital with an average daily census of 3.) The net result is still a large loss for the hospital.

Figure 6

Inpatient Revenue and Costs at a CAH

With Only Acute and Rehabilitation Patients

| Days | Charges | % of Total |

Payment Per Service |

Amount | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Payments | |||||

| Medicare Acute Days Inpatient Cost | 274 | $684,375 | 50% | $2,198 | $602,000 |

| Other Payers Acute Days Inpatient Fee | 274 | $684,375 | 50% | $3,000 | $821,000 |

| Subtotal Acute Days Payments | 548 | $1,368,750 | 100% | $2,599 | $1,423,000 |

| Medicare Swing SNF Days Inpatient Cost | 274 | $205,313 | 50% | $2,198 | $602,000 |

| Other Payers Swing SNF Days Inpatient Fee | 274 | $205,313 | 50% | $800 | $219,000 |

| Subtotal Swing SNF Days Payments | 548 | $410,625 | 100% | $1,499 | $821,000 |

| Total Revenue | 1,095 | $1,779,375 | $2,049 | $2,244,000 | |

| Cost | |||||

| Total Cost | $2,432,000 | ||||

| Margin | |||||

| Margin | ($188,000) | ||||

| Pct Margin | −7.7% | ||||

Cost-Based Payment for a Rural Health Clinic

The table below shows the revenues and costs for a hypothetical Rural Health Clinic that has 9,000 total visits per year. It is staffed identically to the example that was shown for a 10,500-visit clinic in , so it has a total cost of $2.2 million. In addition, at this hypothetical RHC, it is assumed that:

50% of the visits are made by Medicare beneficiaries (who are in the “Original Medicare” program, not a Medicare Advantage plan) and the remainder have an insurance plan that pays fees for services.

For each visit to the clinic, the hospital charges an average of $250, just slightly more than the average cost of a visit.

Insurance plans other than Medicare pay an average of $100 for a visit.

Figure 7

Revenue and Costs for the Rural Health Clinic

at a Hypothetical Rural Hospital

| Visits | Charges | % of Total |

Payment Per Service |

Amount | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Payments | |||||

| Medicare RHC Visits RHC Cost | 4,500 | $1,125,000 | 50% | $234 | $1,053,000 |

| Other Payers RHC Visits RHC Fee | 4,500 | $1,125,000 | 50% | $100 | $450,000 |

| Total Revenue | 9,000 | $2,250,000 | $167 | $1,503,000 | |

| Cost | |||||

| Total Cost | $2,217,000 | ||||

| Margin | |||||

| Margin | ($715,000) | ||||

| Pct Margin | −32.2% | ||||

| Cost Per Service | |||||

| Cost Per Visit | $246 | ||||

The result is a loss of over $700,000 for the hospital. The fees paid by payers other than Medicare, while they are similar to the amounts typically paid for primary care visits, are far below the hospital’s cost per visit. Medicare pays less than the average cost per visit because 9,000 visits is below the minimum that Medicare’s productivity standard requires for full cost-based payment. Altogether, revenues fall more than 30% short of the amount needed to cover the clinic’s costs.

Even if the clinic used fewer physicians and more nurse practitioners, which would reduce the cost of the clinic and avoid the Medicare productivity penalty, the clinic would still lose money. The only way for the clinic to be profitable is for other payers to pay more for visits to the clinic than the amounts typically paid for primary care visits.

The Many Problems with Cost-Based Payment

Cost-Based Payment from Medicare Does Not Solve Hospitals’ Financial Problems

The examples above make it clear that cost-based payment from Medicare does not and cannot eliminate the financial losses that small rural hospitals experience. Although Medicare patients represent a large portion of the patients at rural hospitals, the majority of the patients are insured by payers that do not pay hospitals based on their actual costs:

Medicare Advantage plans are not required to pay Critical Access Hospitals or Rural Health Clinics based on their costs. In fact, Medicare Advantage plans pay small rural hospitals significantly less than the costs of services in two states where data are available.

Commercial insurance plans typically pay for hospital services based on a standard fee schedule or a percentage of the hospital’s charges, not based on the hospital’s actual costs. Commercial insurance plans generally pay the same amount or less for hospital services at small hospitals as they pay larger hospitals, even though the costs at the smaller hospitals are higher, and the health plans pay small hospitals less than Medicare pays.

Commercial insurance plans typically pay for visits with primary care clinicians based on standard fees, regardless of whether the visits are made to an RHC or a physician practice. Hospitals with Rural Health Clinics lose more on privately insured patients than those without an RHC.

Some state Medicaid programs pay Critical Access Hospitals based on their costs, but most do not.15

State Medicaid programs are not required to pay Rural Health Clinics based on their current costs; Medicaid payments are based on an amount calculated based on the costs at the RHC in the past with an adjustment for inflation. The inflation-based increases are often inadequate to cover the actual increases in the costs of employing clinicians and other staff. Although Medicaid payments are supposed to be “rebased” periodically to better reflect actual costs, this is often not done because of the higher payments that would be required.

Although Critical Access Hospitals generally receive a higher amount from Medicare under cost-based payment than they would have under standard Medicare payment systems, the hospital still receives less than the actual cost of care because, under sequestration rules, the Medicare payment is no more than 99% of the actual costs. However, even if the hospital received 101% of its costs, a 1% margin would not be sufficient to offset the losses a typical hospital experiences on uninsured patients, much less on low payments from insured patients.

Cost-Based Payment Penalizes Hospitals for Keeping Patients Healthy

The problem with fee-for-service payment is not just that the amounts paid are generally lower than the costs of services at small hospitals, but the payment system rewards hospitals for delivering unnecessary services and it penalizes hospitals for efforts to keep patients healthy and to make services more affordable for patients. Cost-based payment from Medicare does not eliminate these problems.

When the hospital is paid for ED services with visit-based fees, the hospital will lose money if fewer patients need to visit the ED, and the hospital will benefit financially if more patients have emergencies or use the ED as source of care. The same problem exists under cost-based payment. Because the Medicare payment is based on the proportion of ED charges billed to Medicare patients, if fewer Medicare patients come to the ED, Medicare’s payment will decrease. The table below shows what happens to the ED in Figure 4 if 5% fewer Medicare patients make visits. The cost-based payment from Medicare decreases, so the ED now experiences a loss. Conversely, if Medicare beneficiaries made more visits to the ED, Medicare’s share of the ED cost would increase, and the profit in the ED would increase. If visits by all types of patients decreased proportionally, Medicare’s share of costs would remain the same, and its payments for the ED would remain the same. However, the fee-for-service payments from other insurers would decrease because there were fewer visits, so the hospital would still lose money.

Figure 8

Impact on a Critical Access Hospital ED

of a Reduction in Visits by Medicare Beneficiaries

Baseline

|

Fewer Visits

|

Change | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visits | % of Total |

Amount | Visits | % of Total |

Amount | ||

| Payments | |||||||

| Medicare ED Visits Facility Cost | 6,250 | 50.0% | $1,154,000 | 5,625 | 47.4% | $1,114,000 | −3% |

| Other Payers ED Visits Facility Fee | 5,625 | 45.0% | $675,000 | 5,625 | 47.4% | $675,000 | 0% |

| Uninsured ED Visits Facility Fee | 625 | 5.0% | $0 | 625 | 5.3% | $0 | |

| Subtotal ED Visits Facility Payments | 12,500 | 100.0% | $1,829,000 | 11,875 | 100.0% | $1,789,000 | −2% |

| Medicare ED Visits Physician Fee | 6,250 | 50.0% | $1,113,000 | 5,625 | 47.4% | $1,002,000 | −10% |

| Other Payers ED Visits Physician Fee | 5,625 | 45.0% | $338,000 | 5,625 | 47.4% | $338,000 | 0% |

| Uninsured ED Visits Physician Fee | 625 | 5.0% | $0 | 625 | 5.3% | $0 | |

| Subtotal ED Visits Physician Payments | 12,500 | 100.0% | $1,451,000 | 11,875 | 100.0% | $1,339,000 | −8% |

| Total Revenue | 12,500 | $3,280,000 | 11,875 | $3,129,000 | −5% | ||

| Cost | |||||||

| Facility Cost | $2,313,000 | $2,358,000 | 2% | ||||

| Cost of Clinician Patient Time | $900,000 | $855,000 | −5% | ||||

| Total Cost | $3,213,000 | $3,213,000 | 0% | ||||

| Margin | |||||||

| Margin | $68,000 | ($84,000) | −224% | ||||

| Pct Margin | 2.1% | −2.6% | −224% | ||||

As a result, cost-based payment from Medicare creates the same perverse incentives as fee-for-service payment. For example, if the hospital created more effective care management and preventive care services for patients that reduced the number of ED visits, the hospital would be penalized through greater financial losses in the ED. The same thing would happen if the hospital reduced the number of Medicare beneficiaries needing inpatient care, lab tests, or other services.

Medicare Beneficiaries Pay More for Outpatient Services Under Cost-Based Payment

A Critical Access Hospital is paid more than other hospitals for delivering a service if the cost of the service is higher than the standard Medicare payment. Since Medicare beneficiaries are required to pay 20% co-insurance on outpatient services, this means the beneficiary will also pay more for services at Critical Access Hospitals than at other hospitals.

Moreover, the percentage difference in payment is typically greater for the beneficiary than for the Medicare program, because the beneficiary is required to pay 20% of the hospital’s charge for the service, not 20% of the cost of the service. A hospital cannot possibly break even on a service line if it does not charge more than the cost of services, since it has to make enough profit to cover bad debt and uninsured patients, and it generally has to set charges much higher than costs in order to provide the discounts that private insurance plans require. To the extent that the charge is higher than the cost, the co-insurance for the Medicare beneficiary is also higher.

For example, in the hypothetical ED shown in Figure 3, the hospital’s charge for the facility component of the visit is $750, which is about 60% more than the average $471 cost per visit for the facility component of costs. Medicare beneficiaries are required to pay 20% of that charge, or $150, not 20% of the $471 cost, which would be $94. Since the combined payment from both the beneficiary and Medicare is limited to the hospital’s cost, the beneficiary is actually contributing almost one-third of the total Medicare payment, rather than just 20%.

The discounts demanded by most insurance plans require that hospitals set charges well above the actual cost of most services. These plans usually pay less than 50% of charges, so unless the hospital’s charge for a service is at least twice the cost of delivering the service, it will lose money. The charges for laboratory and radiology services at small hospitals are typically several times the average cost of the service. If the hospital’s charge for a service is 2 times the cost, a Medicare beneficiary who pays 20% of that charge is actually paying 40% of the cost of the service (200% x 20% = 40%), and if the charge is 3 times the cost, the Medicare beneficiary is paying 60% of the cost. An analysis by the HHS Office of Inspector General in 2014 found that Medicare beneficiaries pay nearly half of the costs of outpatient services at Critical Access Hospitals.16

Medicare beneficiaries living in rural areas do not have higher incomes than beneficiaries living in urban areas, and they generally have lower incomes, so the higher co-insurance amounts create more of a financial burden for them. If they are unable to pay the full co-insurance amount, the hospital will have a higher loss from bad debt. Unlike private insurance plans, Medicare reimburses hospitals for 65% of bad debt on Medicare patients, but it does not cover the full amount, so more bad debt due to higher co-insurance payments will mean larger losses for hospitals.

Cost-Based Payment Creates a Much More Complex Payment System for Small Hospitals

Fee-for-service payment is often criticized for its complexity, but cost-based payment is even more complex:

The hospital still has to submit a claim for each individual service delivered to Medicare beneficiaries. However, estimating the amount of payment it will receive for the claims requires determining the eligible costs of each service line, apportioning those costs to Medicare based on how many patients with other types of insurance received the service, determining patient cost-sharing based on the charge instead of the payment, and many other steps.

The initial payment the hospital receives is based on the estimated costs of services in the current year. Medicare then reconciles the initial payments against the actual costs to determine the final payment. This can result in the hospital having to repay Medicare if the estimated costs were higher than the actual costs.

In states that use Medicaid Managed Care Organizations (MCOs), the MCOs are only required to pay RHCs the standard fees they pay primary care practices, so the state has to make separate “wrap-around” payments to the RHC to make up the difference between those fees and the amounts the Medicaid agency is required to pay. This requires the hospital to submit two separate bills for each clinic visit – one to the MCO and one to the state Medicaid agency.

This greater complexity might be acceptable if cost-based payment produced better results for rural hospitals and their patients than fee-for-service, but as discussed above, rural hospitals can still lose large amounts of money on core services even with cost-based payments from Medicare. Moreover, if the hospital has to hire more staff or pay more to consultants in order to successfully manage this complexity, it will increase administrative costs at the hospital and increase its financial losses.

Does Cost-Based Payment Increase the Cost of Care?

The obvious concern about cost-based payment is that it will encourage inefficiency and result in higher-cost care, which is why Medicare changed from a cost-based payment system to the IPPS in 1983. However, the cost-based payments from Medicare for Critical Access Hospitals do not reward the hospitals for being inefficient, for several reasons:

- If a hospital were to increase the amount it spends on a service line unnecessarily, e.g., by hiring unnecessary staff, or paying wages higher than necessary to fill positions, it would be worse off financially because only Medicare would pay more, and the higher payment from Medicare would not cover the increase in costs. For example, if Medicare beneficiaries receive half of the services at the hospital, and if the hospital’s total cost increases by 10%, then the cost-based payment from Medicare would increase by 10%, but that higher revenue would cover at most 50% of the higher cost. Since other payers do not pay based on costs, the hospital’s revenue from other payers would not change, and profits would decrease or losses would increase by the amount of the increase in costs that is not assigned to Medicare patients.

- If the hospital increased its charges in an effort to cover more of the increased costs, Medicare beneficiaries would have to pay higher co-insurance payments (since their co-insurance is 20% of the hospital’s charge), which could increase the hospital’s bad debt and discourage beneficiaries from seeking services from the hospital. That could result in less Medicare revenue than expected, increasing losses.

- Under sequestration rules, Medicare only pays 99% of costs, so if costs increase, the hospital also loses more on Medicare patients.

While the cost-based payments from Medicare do not encourage inefficiency, neither do they encourage efficiency. If a hospital reduces its cost in a service line, Medicare payments will decrease proportionally. The reduction in cost will improve the hospital’s margin for non-Medicare patients, but not for Medicare patients.

Cost-Based Payment Doesn’t Solve Rural Hospital Problems

For most very small rural hospitals, cost-based payment from Medicare will result in lower operating losses than standard Medicare payments because the cost per service at those hospitals is higher than standard Medicare payment amounts. As shown in Chapter II, small rural hospitals that are not designated as Critical Access Hospitals have significantly higher losses on their Medicare patients than those which receive cost-based payments.

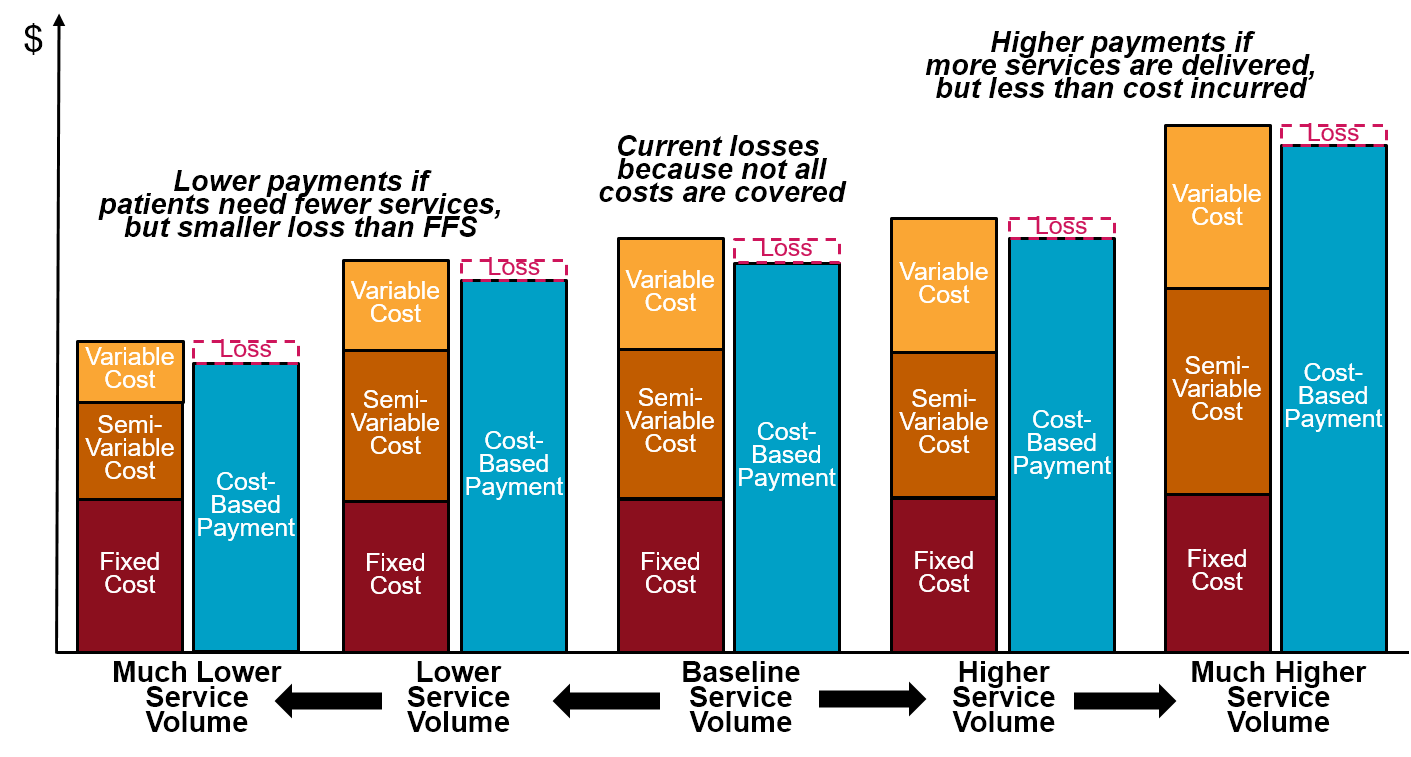

However, as shown in Figure 1, most Critical Access Hospitals still lose money on patient services overall. Cost-based payment from Medicare can reduce losses at a hospital but it cannot eliminate them because there are no profits on the Medicare patients that can offset losses on other patients. No matter whether the hospital delivers more services or fewer services, the hospital still loses money.

Even if federal sequestration reductions were permanently eliminated for Critical Access Hospitals, a 1% profit margin on services to Medicare patients would not be enough to offset the significant losses most small rural hospitals experience on uninsured patients, Medicaid patients, and patients with Medicare Advantage or commercial insurance plans. Proposals to expand the number of hospitals that qualify for Critical Access Hospital status would likely only prevent closures of hospitals that have unusually high percentages of Medicare patients or that have high payments from private insurance plans.

As shown in Section 2, the biggest cause of financial problems at most small rural hospitals is low payments from private payers. If private health plans that currently pay less than the cost of services at Critical Access Hospitals began paying amounts equal to 101% of the cost of care for patients insured by those plans, losses would be reduced significantly for those hospitals, and some would become profitable overall. Moreover, cost-based payment for all patients would reduce or eliminate the problematic incentives created by fee-for-service payment discussed earlier. For example, if a hospital created a care management program for individuals with chronic diseases that reduced the frequency with which those patients made ED visits or were admitted to the hospital, the hospital would no longer lose money simply because fewer patients needed services.

However, even though cost-based payment from private payers in addition to Medicare would have many benefits for small rural hospitals compared to current payment systems, it has a fatal flaw. As noted earlier, the reason that cost-based payment from Medicare does not result in significant inefficiency at hospitals is because other payers do not pay based on costs. If every payer paid a hospital at least 100% of its share of the hospital’s costs, there would no longer be any incentive for efficiency. A hospital could hire unnecessary employees, pay employees higher-than-necessary salaries, purchase unnecessary equipment and supplies, etc. with no concern about losing money because the cost-based payments would increase sufficiently to pay for those higher costs. If some payers paid 101% or more of costs, then the hospital could actually make higher profits by spending more money, which would result in higher spending by both patients and insurance plans with no corresponding improvement in the quality of care.

Figure 9

How Changes in Volume Affect Margins Under Cost-Based Payment

Although small rural hospitals need a different payment system from private payers, it cannot be the cost-based payment system used by Medicare. Moreover, because of the problems with the Medicare system, small rural hospitals also need a better payment system from Medicare. Alternatives are needed that provide the benefits of cost-based payment without the problems.

Footnotes

Smith DG. Paying for Medicare: The Politics of Reform. Aldine de Gruyter 1992.↩︎

Although the Diagnosis Related Group (DRG) payments in the IPPS are not typically described as “fees,” a fee is simply a predetermined amount paid for a service, and a DRG payment in IPPS is a fixed amount paid when a service (a hospital admission) is delivered.↩︎

United States General Accounting Office. Rural Hospitals: Factors That Affect Risk of Closure. GAO Report HRD-90-134 (June 1990).↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

42 U.S.C. 1395i–4↩︎

Medicare increases payments to other hospitals based on the amount of uncompensated care the hospital delivers, but there is no similar payment adjustment for Critical Access Hospitals.↩︎

The sequestration reduction was first imposed on April 1, 2013. The reduction was temporarily suspended during the coronavirus pandemic for services delivered between May 1, 2020 and March 31, 2022.↩︎

The 101% calculation is performed before the patient contribution is deducted, but the 2% sequestration reduction is performed after the patient contribution deduction, so the total amount the hospital receives will generally be higher than 99% of costs, particularly for certain kinds of outpatient services. For example, if the total outpatient cost attributable to Medicare beneficiaries was $1 million and the charges for those beneficiaries totaled $2 million, then the total payment in step 2 would be $1,010,000 (101% of $1 million), the patients would be expected to contribute $400,000 (20% of $2 million), Medicare would be responsible for $610,000, sequestration would reduce the Medicare payment to $597,800, and so (assuming the patients paid their full cost-sharing amounts) the hospital would receive $997,800, or 99.8% of the cost. The total Medicare payment will never be more than 100%, however.↩︎

Cost-based payment for Rural Health Clinics was first authorized by Congress in 1977 in an effort to address shortages of physicians in rural areas.↩︎

RHCs at hospitals with more than 50 beds, and RHCs that are not based at hospitals, can also receive “cost-based” payments from Medicare, but for these RHCs, the payment per visit can be no higher than a maximum ceiling established by Medicare. The ceiling in 2020 was $86.31 per visit, which is far below what the cost per visit at an RHC would likely be. This means that as a practical matter, most Rural Health Clinics that are not owned by hospitals are paid on a fee-for-visit basis with fees equal to the payment ceiling, rather than based on their actual costs. The Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021 will increase the payment ceiling for free-standing significantly each year until it reaches $190 per visit in 2028, and it imposes the same ceiling on new hospital-based RHCs. While the law permits existing hospital-based RHCs to continue receiving cost-based visit payments higher than the ceiling, it limits the amount by which the payments per visit at those RHCs can increase each year even if increases in costs would have resulted in a higher payment in the past.↩︎

Most ED visits with physicians are classified as Level 4 or Level 5 visits. In 2018, Medicare paid ED physicians $119.52 for a Level 4 ED visit and $176.04 for a Level 5 ED visit. Assuming that two-thirds of visits at small rural hospitals are Level 5 visits and one-third are level 4, the average payment would be $157.20. Hospitals that bill for the physician services are paid 15% more than the standard fees, bringing the average to $180.78. Sequestration on the Medicare portion of the payment will then reduce the amount to $178.↩︎

In the example, the fees Medicare pays for physician visits are higher than the cost of the portion of the physician’s time allocated to visits, which more than offsets the losses from the low payments from private payers.↩︎

Under the cost-based payment system, it is more difficult for the hospital to reduce its losses by reducing costs than under fee-for-service payment, because when the cost of a service line is reduced, the amount of cost-based payment from Medicare would also decrease. Moreover, if the overhead cost from one cost center is reassigned to another cost center, it will simply increase losses in those other cost centers.↩︎

Rural Hospitals and Medicaid Payment Policy. Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (August 2018).↩︎

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Medicare Beneficiaries Paid Nearly Half of the Costs for Outpatient Services at Critical Access Hospitals. Office of Inspector General Report OEI-05-12-00085 (October 2014)↩︎