| Community Residents |

Payment Per Resident |

Visits | Payment Per Service |

Amount | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standby Capacity Payments | |||||

| ED Standby Pmt | 23,750 | $100 | $2,375,000 | ||

| Service-Based Fees | |||||

| Residents | 23,750 | 11,250 | $65 | $731,000 | |

| Non-Residents | 0 | 625 | $325 | $203,000 | |

| Uninsured | 1,250 | 625 | $0 | $0 | |

| Subtotal | 12,500 | $934,000 | |||

| Total Payments | |||||

| ED Standby Payments | 25,000 | $95 | $2,375,000 | ||

| ED Visit Payments | 12,500 | $75 | $934,000 | ||

| Total Revenue | $3,309,000 | ||||

| Cost | |||||

| Total Cost | $3,213,000 | ||||

| Margin | |||||

| Margin | $97,000 | ||||

| Pct Margin | 3.0% | ||||

| Average Cost | |||||

| Cost Per Visit | $257 | ||||

| Cost Per Resident | $129 | ||||

Patient-Centered Payment

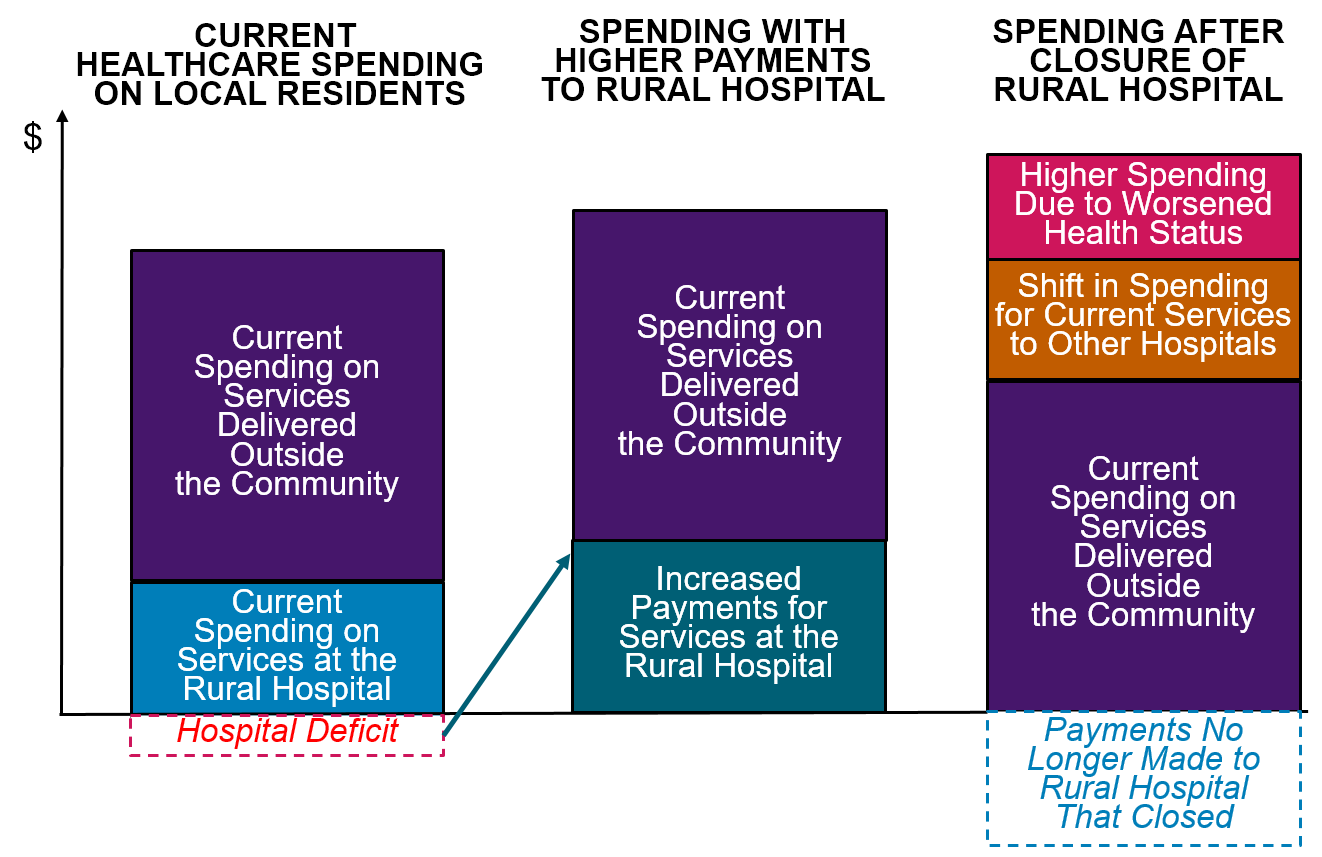

A good payment system for rural healthcare must achieve three key goals:

- Ensure availability of essential services in the community;

- Enable timely delivery of the services patients need; and

- Support delivery of appropriate, high quality, affordable care.

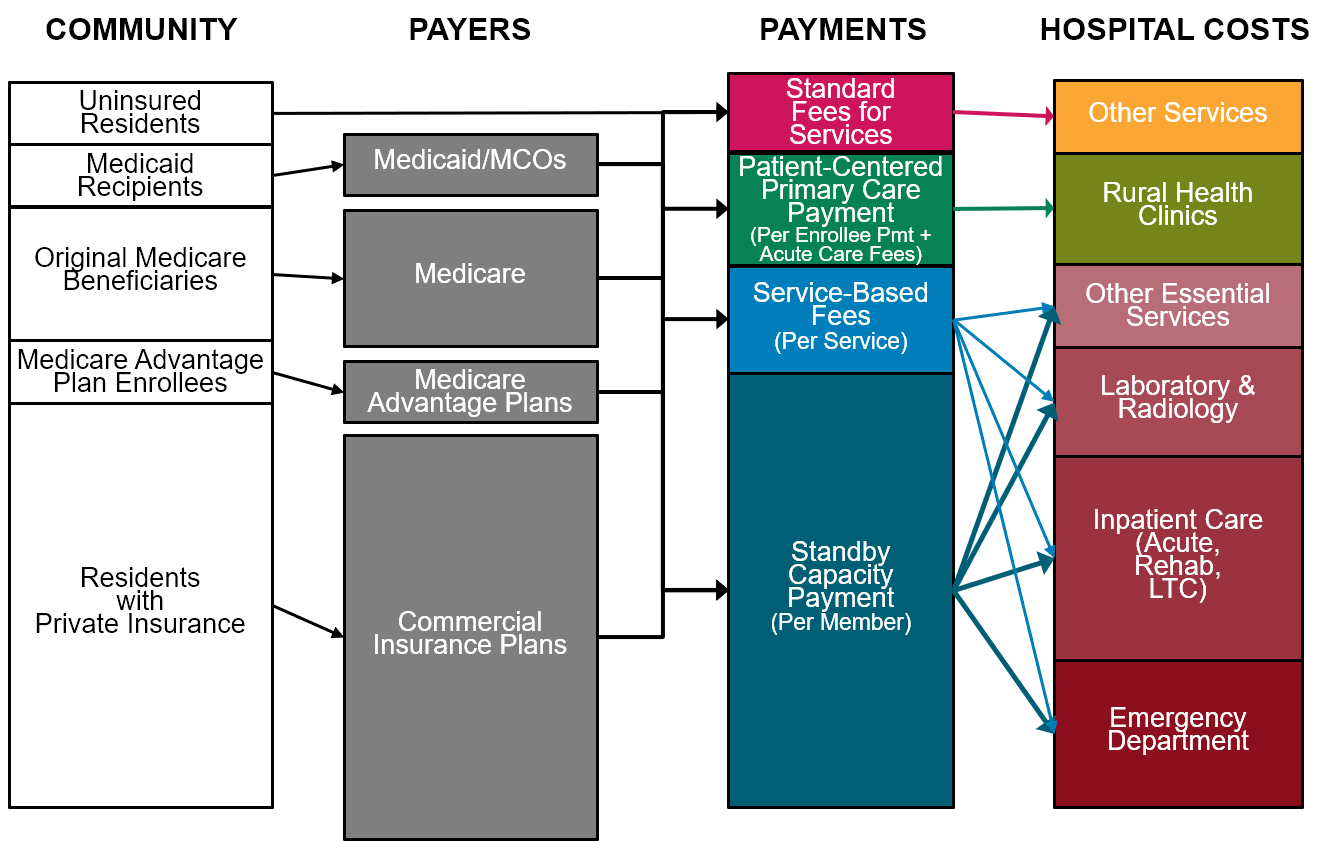

Patient-Centered Payment for rural hospitals can achieve all three goals through the following four components:

- Standby Capacity Payments to support the fixed costs of essential services;

- Service-Based Fees for diagnostic and treatment services based on variable costs;

- Accountability for quality and efficiency; and

- Value-based cost-sharing for patients.

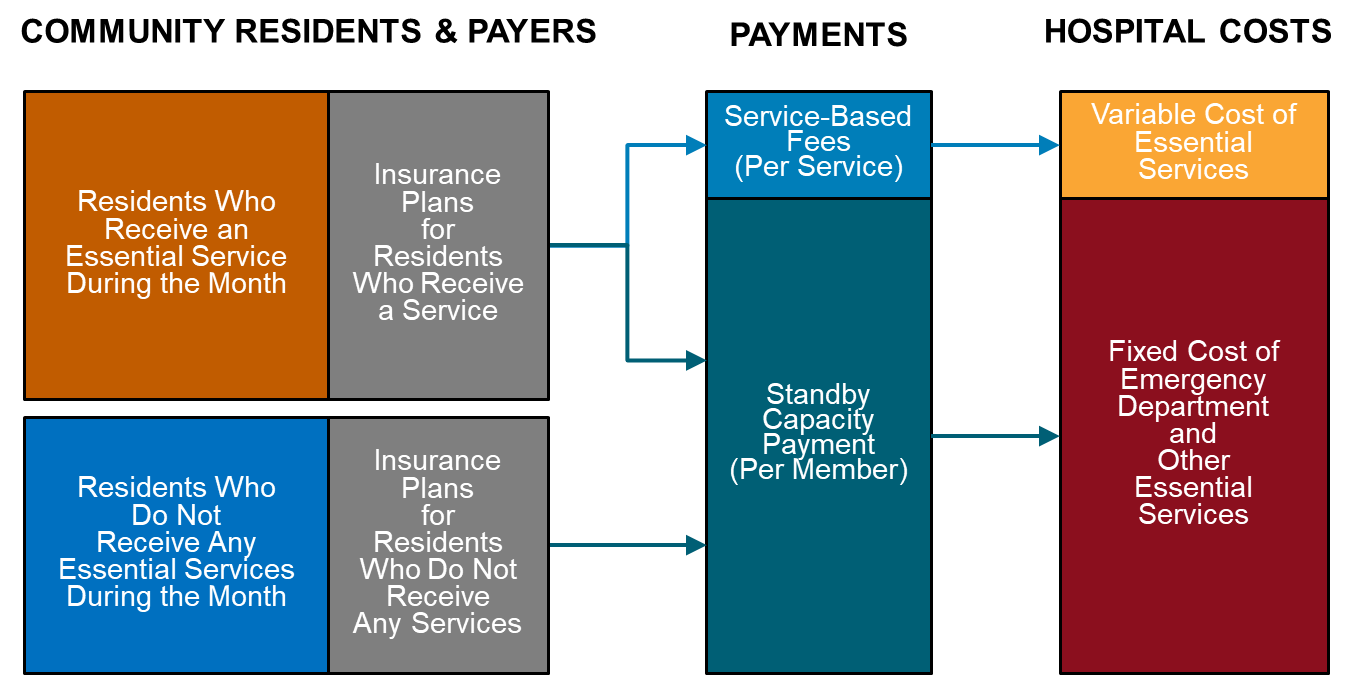

Standby Capacity Payments would be based on the number of community residents, not the number of services delivered. A Standby Capacity Payment would be paid to a rural hospital by each health insurance plan (Medicare, Medicaid, Medicare Advantage, and commercial insurance) based on the number of members of that plan who live in the community, not based on the number of services the patients receive. This ensures the hospital has adequate revenues to support the minimum standby costs of the emergency department, inpatient unit, laboratory, etc. regardless of how many patients actually need services during any given month or year.

Service-Based Fees would be much lower than current fees because they can be based on the variable (incremental) cost of services rather than the average cost. If the hospital is receiving Standby Capacity Payments that support the fixed costs of essential services, the fees for individual services only need to cover the additional costs incurred when additional services are delivered.

Payment amounts need to be adequate to support the cost of delivering high-quality care. The method of payment in a Patient-Centered Payment system would avoid the serious problems associated with fee-for-service payments, cost-based payment, global budgets, and shared savings programs. However, no payment system will prevent hospital closures unless the amounts of payment are large enough to cover the cost of delivering high-quality care in small rural hospitals.

Hospitals should accept accountability for delivering appropriate, high quality care. In return for receiving adequate payments to support essential services, rural hospitals need to take accountability for delivering evidence-based services safely and efficiently.

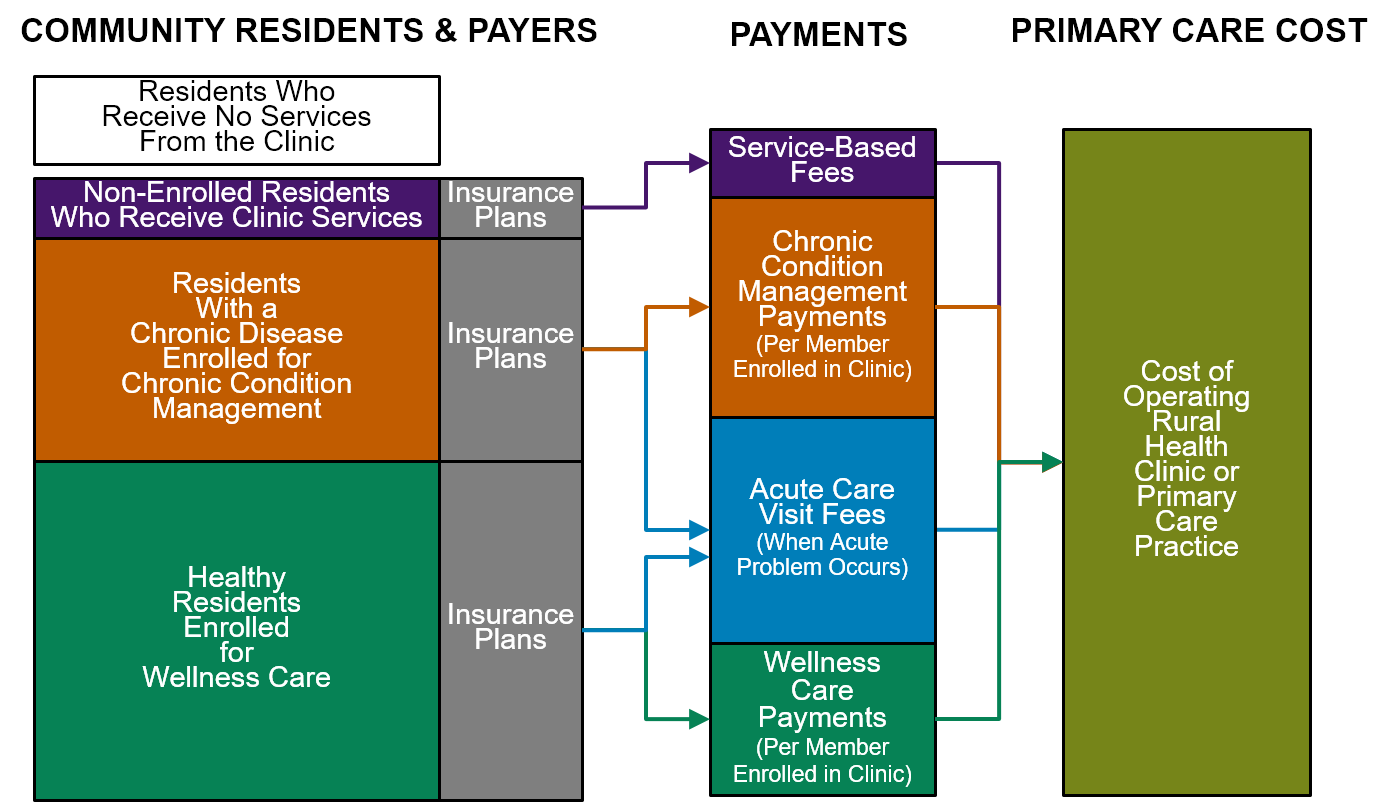

In addition to Patient-Centered Payment for hospital services, the hospital’s Rural Health Clinic(s) should be paid using Patient-Centered Primary Care Payment. The Rural Health Clinic (or other primary care practice operated by the hospital) should be paid based on the number of patients enrolled for primary care and the needs of those patients, not the number of visits patients make to the clinic. The Rural Health Clinic or primary care practice should receive a monthly Wellness Care Payment from the health insurance plan of an insured member who enrolls with the clinic for ongoing primary care, and an additional monthly Chronic Condition Management Payment if the patient has a chronic health problem. The clinic should have the flexibility to deliver proactive wellness care and chronic disease management services using nurses, medical assistants, or community health workers, rather than only through visits with physicians or other clinicians. In addition, the Rural Health Clinic or primary care practice should receive an Acute Care Visit Fee when the patient had a new acute problem, but the patient should be able to receive help through telehealth when appropriate rather than only through in-person visits at the clinic. Higher amounts should be paid for patients who have higher needs to ensure all patients could receive high-quality care.

Goals for Rural Hospital Payment

How should a small rural hospital be paid? A good payment system would achieve three key goals:

- Ensure availability of essential services in the community. A rural community needs to have assurance that its hospital’s emergency department and basic diagnostic and treatment services will be available to deliver high-quality services at all times. There is a minimum cost involved in providing this capacity in a small community, and the hospital needs to have sufficient revenue to cover that cost, regardless of how many people actually have emergencies or illnesses requiring diagnosis and treatment. Payments based solely on the number of services delivered may not generate sufficient revenues to cover this cost, and an arbitrary global budget may also fail to do so.

- Enable timely delivery of the services patients need. When community residents have health problems, payments should enable the hospital to provide appropriate diagnostic and treatment services as quickly and efficiently as possible. The hospital should not be prevented from delivering services to all patients who need them by an arbitrary cap on its revenues, nor should it be paid the same amount even if it delivers fewer services than patients need, which is what would happen under a global budget. Moreover, insurance plans should not discourage or prevent patients from obtaining high-quality care by requiring high cost-sharing amounts or refusing to pay for services at the community hospital.

- Support delivery of appropriate, high quality, affordable care. Hospitals should be paid adequately to deliver services safely, efficiently, and in ways that evidence indicates will achieve good outcomes. The payment system should not reward hospitals for delivering unnecessary services or for charging prices that are higher than necessary, nor should it financially penalize hospitals for preventing complications and improving patient outcomes, as happens under the fee-for-service system. The payment system should also not reward a hospital for reducing access to services for patients or pay the hospital even when it delivers low-quality care, as a global budget would.

Patient-Centered Payment for Rural Hospitals

A Patient-Centered Payment system that achieves all three goals would have four components:

- Standby Capacity Payments to Support the Fixed Costs of Essential Services. The hospital should receive a Standby Capacity Payment from health insurance plans for each person living in the community served by the hospital, regardless of how many services those people actually receive. These payments would be designed to pay for the minimum fixed costs required to adequately staff an Emergency Department and other essential service lines.

- Service-Based Fees for Diagnostic and Treatment Services Based on Variable Costs. The hospital should also receive a Service-Based Fee when a patient receives a specific service. This payment would only need to cover the variable costs of the service, since the minimum fixed costs would be paid for by the Standby Capacity Payments. As a result, the Service-Based Fees would be smaller than current fee-for-service payments.

- Accountability for Quality and Spending. In order to receive adequate payments to support delivery of services, hospitals should be required to deliver services in accordance with evidence-based Clinical Practice Guidelines and to do so safely and efficiently.

- Value-Based Cost-Sharing for Patients. The amounts that patients have to pay out of pocket for high-value services should be set at levels that the patient can afford, thereby enabling the patients to obtain the care they need to improve their health and avoid the need for more expensive services.

This is a patient-centered approach to payment because it is designed to support the services that patients need, not to increase profits for either hospitals or health insurance plans.

More details on each of these components are provided below.

Standby Capacity Payment to Support the Fixed Costs of Essential Services

The Need to Pay Directly for Hospital Standby Capacity

The fee-for-service payment system includes fees for thousands of individual healthcare services, but there is no fee at all for what residents of a rural community would likely view as the most important service of all – the availability of physicians, nurses, and equipment to diagnose and treat a serious health problem if the resident experiences an injury or illness.

The hospital’s ability to deliver a service on short notice is often referred to as “standby capacity,” because a minimum level of personnel and equipment must be standing by at all times in case a patient needs the service, even if it turns out that no patient actually does need it. In most medium-sized and larger hospitals, there is little “standing by” in the ED, because patients are coming to the ED almost continuously around the clock, but in a small rural hospital, the ED is not in continuous use, and therefore special efforts are needed to ensure the hospital has adequate standby capacity in the ED so that patients can be treated in a timely fashion when they do need care. Similarly, in a small community, no laboratory tests may be needed on some nights, weekends, or even weekdays, but the laboratory must still have the ability to perform tests if they are needed in an emergency.

The coronavirus pandemic made many people aware for the first time that current payment systems do not ensure that hospitals have enough standby capacity to handle unexpectedly large increases in patient needs, including very large hospitals. The need for standby capacity is greatest, however, in small rural communities, because even a small increase in the number of patients represents a large percentage increase for the hospital if its average volume of cases is low. Moreover, whereas large hospitals will typically have other hospital units that can be repurposed during an emergency, and most large hospitals will have sufficient financial reserves to bring in additional staff to handle unexpected increases in volume, the small size and low margins at small rural hospitals have not allowed them to create similar capacity and reserves.

The Problems with Charging Higher Service Fees to Support Standby Capacity

Hospitals have traditionally paid for standby capacity by charging higher amounts for individual services or charging separate “facility fees.” However, this approach is problematic for multiple reasons:

- Prices for services are higher than costs. Charging more for each individual service in order to cover standby capacity costs makes the price of the service higher than the additional cost of delivering it. That increases the financial incentive for the hospital to deliver unnecessary services and increases the financial penalties when the hospital avoids delivering unnecessary services or improves patients’ health so they need fewer services.

- Services are less affordable. Charging more for a service makes the service less affordable for patients; that can either discourage them from getting needed services altogether, or encourage them to seek the service elsewhere, both of which reduce the hospital’s ability to sustain its services. This problem is more severe at a small rural hospital than at larger hospitals because a higher proportion of the rural hospital’s costs are for standby capacity, so the higher fees that are often needed to support the higher costs of personnel and supplies in rural areas become even higher in order to cover standby capacity costs.

- Services are not being supported equitably by those who benefit from them. Obtaining revenue only from those individuals who receive services means that healthy community residents are not paying at all to sustain the standby capacity that they want and need to have available in their community.

Making Payments Specifically for Standby Capacity

Communities do not force their fire department to support itself by charging high fees for extinguishing fires. The residents of the community provide funding to the fire department to ensure it has adequate equipment to fight fires, and they provide either funding or in-kind resources (i.e., volunteer firefighters) to ensure the department has adequate personnel.

Small rural hospitals need to receive similar support for their standby capacity. Rather than only receiving a payment for each patient who actually receives services from the ED during the month, the hospital needs to also receive a payment for each potential patient, i.e., each community resident who does not happen to need the ED during a particular month, but who benefits from having the ED and associated ancillary services available in case they do.

Standby capacity is an important healthcare service, because failure to provide it can result in worse outcomes and higher healthcare spending for residents of the community. Consequently, payments to support standby capacity should come from health insurance plans.1

Support for standby capacity can be provided by paying the hospital a monthly Standby Capacity Payment (SCP) for each resident of the community in the following way:

- All health insurance plans (Medicare, Medicare Advantage, Medicaid, and commercial insurance) should pay a Standby Capacity Payment for each of their members who live in the community served by the hospital. For each resident of the hospital’s service area who has health insurance, their insurance plan would pay the Standby Capacity Payment to the hospital each month. Health insurance plans receive a monthly premium for each of their members which are supposed to be used to ensure the member can receive the healthcare services they need, so it is appropriate for a portion of that premium to be paid to the community hospital to ensure that it is ready to deliver those services to the plan’s members when they need them. This per-member payment would be paid by the insurance plan in addition to Service-Based Fees for any individual services the insurance plan member receives if they go to the hospital for care.

- The hospital’s total revenue from Standby Capacity Payments should cover the fixed cost of adequate standby capacity. In aggregate, the Standby Capacity Payments from all payers should be sufficient to support the fixed costs of adequate staffing and equipment for the hospital’s Emergency Department services, laboratory and radiology services, basic inpatient care, and other essential services, i.e., the cost that the hospital would have to incur even if only a small fraction of community residents actually need to use the services in any particular month.

A separate Standby Capacity Payment should be paid to a hospital if it delivers specific types of services (e.g., labor and delivery services or inpatient psychiatric services) to a broader service area. This enables the insurance plans for residents of other communities to pay to support the standby capacity needed for those specific services.

Many rural communities currently use local taxes to cover the financial losses their hospitals incur delivering services to community residents. These local tax levies could be reduced if the hospital receives adequate Standby Capacity Payments from health insurance plans that would be funded by the premiums local residents and businesses have already paid for their health insurance.

Figure 1

Standby Capacity Payments Support the Fixed Costs of Essential Services

Focusing Standby Capacity Payments on Essential Services

A hospital should not receive Standby Capacity Payments (through health insurance) for services that would not be considered essential to offer locally, or if there are other providers already offering adequate access to a service in the same community. For example:

- if a non-emergency specialty service (e.g., a rheumatologist or dermatologist) is available in a nearby town and the subset of residents who need that service can obtain it either through a short drive or a telehealth connection, there would not be any justification for providing a Standby Capacity Payment to subsidize offering that service directly within the community itself.

- if a community already has one or more providers of a service that have adequate capacity to meet the community’s needs, the hospital should not receive a Standby Capacity Payment for that service, although it could still operate the service and charge fees to pay for the services that are delivered. For example, if a community has one or community pharmacies, the hospital should not receive a Standby Capacity Payment to operate its own outpatient pharmacy. On the other hand, if the community has no community pharmacy because the number of residents in the community is not sufficient to sustain one, then it could be appropriate to pay a Standby Capacity Payment to the hospital in order to open an outpatient pharmacy.

If a community wants to enable delivery of a service locally where local access is desirable but not essential, it could choose to provide a subsidy similar to a Standby Capacity Payment, but do so using funding sources other than payments from health insurance plans. For example, if residents of a community wanted to have a specialty service available locally without the need to travel or use telehealth connections, but if it would be impossible to financially sustain local delivery of the service using standard payments because of the small number of patients, the community could decide to provide funding to the hospital to support that service using monies from local tax revenues or voluntary contributions, rather than from health insurance plans.

Standby Capacity Payments Can Also Be Used With Larger Hospitals

Standby Capacity Payments could be used to pay for standby capacity at larger rural hospitals and at urban hospitals, not just small rural hospitals. The same problems with fee-for-service payment that make it difficult for a small rural hospital to sustain an Emergency Department or laboratory also make it difficult for a larger hospital to sustain a Trauma Center, Stroke Center, and other service lines that need to be ready to provide services on a round-the-clock basis but are not actually used continuously. Currently, the residents of the region served by the larger hospital benefit from having these services available, but they and their insurance plans provide no financial support for them unless they actually use them.

Many hospitals charge high prices for all of their services and justify doing so based on the need to maintain standby capacity, even though many of the services are not available on a 24/7 basis and even though the extra revenue generated through the higher charges may be far more than is needed to sustain the services that do need to be available on a round-the-clock basis. Paying directly to support Standby Capacity at these hospitals would enable fairer pricing of services and more equitable financial support from patients and payers.

Moreover, it is much easier to define a Standby Capacity Payment for a specific service line at a larger hospital than it is to define a global budget for a large hospital. If there are several hospitals in the community but only one is providing a particular type of service (e.g., a Level I Trauma Center), then a Standby Capacity Payment can be paid to that hospital for that specific type of service, and the payments can be made for each individual who lives in the geographic area that depends on that service, including residents of a rural community that relies on having the service available so it can transfer local residents when they need it.

If two or more hospitals in the same community are providing a service that requires standby capacity (e.g., two hospitals have emergency departments and cardiac catheterization capabilities), and there are not distinct geographic sub-areas served by each, then the amounts of the Standby Capacity Payments for each hospital can be set based on the proportion of the residents who actually use the services for urgent needs. Elective services can then continue to be paid for using standard fee for service methods.

Service-Based Fees for Diagnostic and Treatment Services Based on Variable Costs

The Problems with Fees Based on Average Costs

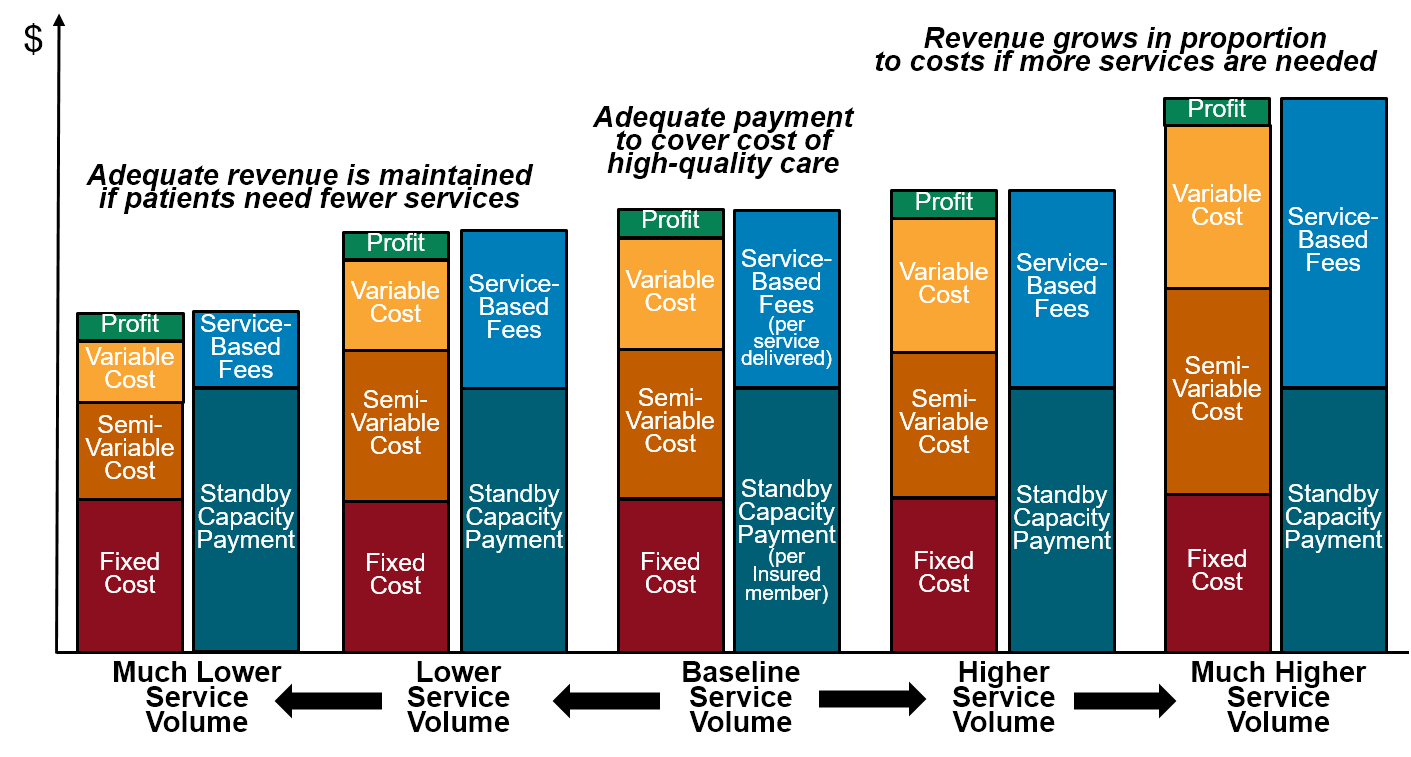

In a fee-for-service payment system, a hospital will only break even financially on a service line if the fees paid for the services are equal to the average cost per service. However, because a high proportion of the costs in most service lines are fixed or semi-variable in nature, the average cost per service changes whenever the number of services changes, so the fee amounts will always be either too high or too low. If fee levels are set based on the average cost of services at a particular level of volume, the hospital will make higher profits when more services are delivered and it will lose money when the number of services decreases.

Paying Separately for Variable Costs

If a hospital receives Standby Capacity Payments to support the minimum fixed cost of operating a service line, it will still need to charge fees for individual services to support any incremental costs associated with delivering more than a minimal number of services. However, those fees can be lower than they are today because they will no longer need to cover the fixed costs of the service line that are paid through the Standby Capacity Payment. Rather than basing fees on the average cost of services as is done under fee-for-service systems, Service-Based Fees under a Patient-Centered Payment System can and should be based on the variable cost of delivering services, i.e., the additional cost the hospital incurs when it delivers additional services. If fees for services are set at levels based on the variable cost of additional services, then the hospital will not make significant profits by delivering more services nor will it incur significant losses when fewer services are delivered.

Using two different types of payments to support a service line – a Standby Capacity Payment based on fixed costs, and Service-Based Fees for individual services based on variable costs – will do a much better job of matching the hospital’s revenues to its costs than either paying fees only when services are delivered, or paying a single global budget regardless of how many services are delivered. Moreover, using two different payments (the Standby Capacity Payment and the Service-Based Fee) is a more equitable way of charging patients (and their health insurance plans) for services than either traditional fees or global budgets, since patients who use more services will pay more but patients who need few services will still help support maintaining the capacity needed for them to receive services when they do need them.

Figure 2

Impact of Changes in Volume on Hospital Margins Under a Patient-Centered Payment System

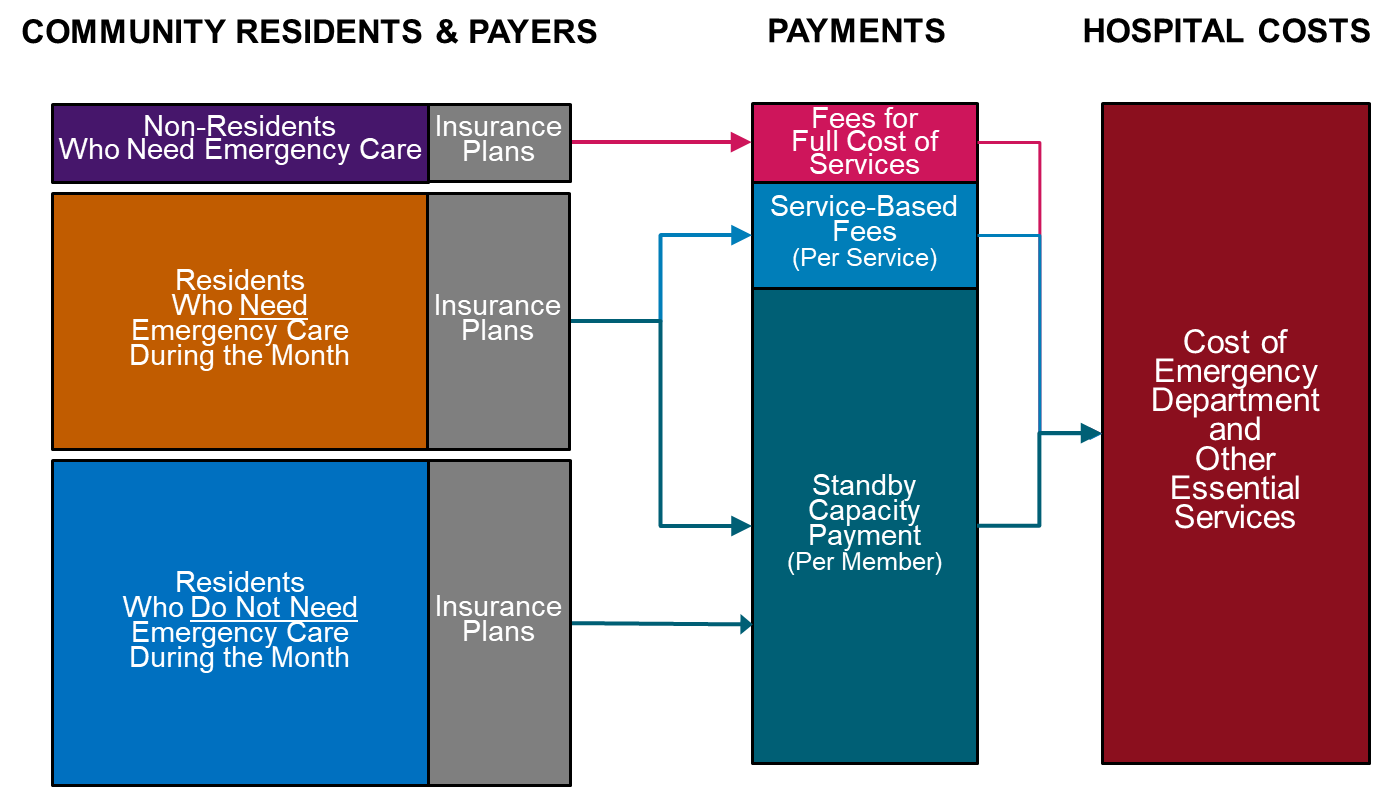

Higher Service-Based Fees for Non-Residents and Members of Non-Participating Insurance Plans

Although most of a rural hospital’s standby services are provided to residents, some are provided to non-residents who work in the community and to tourists and other visitors. The hospital will not receive Standby Capacity Payments for these non-residents, so it is unfair to charge the non-residents the same amount for a service as the amount charged when a resident receives a service. Moreover, in communities that have a lot of non-resident workers or visitors (e.g., in agricultural communities or tourist areas), the hospital may need to provide additional standby capacity in order to deliver the higher volume of services, and it would be inappropriate to charge the insurance plans of the residents more for this.

To address this, the hospital would need to charge non-residents a higher amount for each service than it charges a resident who receives the same service, with the amount for the non-resident based on the average cost of services rather than the variable cost of services. This does not mean that the hospital is charging two different prices for the same service; it is merely collecting payments in two different ways – a two-part payment for residents and a single payment for non-residents. In effect, the hospital is giving a discount to the residents’ health insurance plans for individual services to reflect the Standby Capacity Payments they have made separately.

A similar approach would need to be used for any residents of the community whose health insurance plans are unwilling to pay Standby Capacity Payments for their members. These health plans would have to pay higher Service-Based Fees for essential services that are delivered to their members than the amounts paid by other health plans.

Residents of the community who could afford to purchase health insurance but instead choose to “self-insure” could voluntarily agree to participate in the Patient-Centered Payment system by paying monthly Standby Capacity Payments to the hospital directly. In return, they would pay much smaller Service-Based Fees to the hospital when they did need a service. In effect, the individual would be “pre-paying” for a portion of their hospital care. This is actually the way that Blue Cross insurance plans originally started – residents of the community made regular payments to the local hospital to ensure they could receive hospital care if they needed it, and the hospital received a more reliable stream of revenue than it would if it depended only on sick patients to pay the bills.2

Figure 3

Standby Capacity Payments Allow Lower Fees for Residents Who Need Emergency Care

Cost-Based Payment for Drugs and Medical Devices

For drugs and medical devices, a relatively small proportion of the cost to the hospital represents a fixed or standby capacity cost; the fixed costs consist primarily of whatever staff or equipment are used to store and dispense drugs (many small hospitals may rely on an external pharmacy for much of this), and the cost of any expensive drugs or devices that the hospital needs to keep in stock in case of emergencies but which may not be used before their expiration dates. In addition, although the costs will vary based on how many patients need treatment, the primary driver of the variation will not be the number of patients treated but the specific types of drugs and devices the patients need and the amounts the hospital has to pay for them.

While charging predetermined Service-Based Fees based on expected variable costs is both feasible and desirable in other service lines, it is problematic for small rural hospitals to receive predetermined fees for drugs and medical devices, or to have those payments bundled together with payments for other services as Medicare does in its payment systems. Because of the small quantities of drugs and devices small hospitals purchase, they have little or no ability to negotiate low prices from suppliers, particularly for expensive drugs that do not have generic equivalents. Moreover, the need to use an unusually expensive drug or a large increase in the price of a drug or device can have a large financial impact on a small hospital.

Consequently, the most appropriate approach to pay for variable costs in these cases is to reimburse the hospital for its actual acquisition costs for the drugs and medical devices that are used. This is similar to the cost-based payment approach used by Medicare to pay Critical Access Hospitals, except that the cost-based payment would be limited to the direct costs of the drugs and devices, and all administrative and indirect costs would need to be supported through payments made on the hospital’s other service lines.

Using Bundled Payments vs. Separate Fees for Individual Services

The fees that hospitals currently charge for services are generally associated with relatively narrowly defined services, i.e., there is a separate, different fee for each lab test or imaging study performed, each day of inpatient care received, etc. This approach provides the flexibility to customize the payment based on the exact services a patient received, so that the hospital receives higher fees for services that cost more to perform, and so the patient and insurance plan spend less if fewer services are needed and pay more if more services were needed.

Because of concerns that this system encourages hospitals to deliver unnecessary services, Medicare and many other payers use “bundled payments” for certain groups of related services. The earliest example of this was the case rate (“DRG”) payments Medicare began using to pay for inpatient care in 1983; under this system, the hospital receives a single payment for an inpatient admission, rather than separate payments for each day of care, each lab test performed during the stay, etc. In general, bundled payments have been found to reduce the growth in spending compared to unbundled payments, although the savings varies significantly depending on what is being bundled.3 But because bundled payment amounts are based on the “average” set of services delivered in the bundle, they can cause financial problems for a small hospital when one or more of the patients it treats need more than the average number of services that was used to determine the bundled payment amount.

There is nothing about the use of Standby Capacity Payments that precludes using case rates or bundled payments to pay for the incremental costs of individual inpatient admissions or outpatient services rather than paying separate Service-Based Fees for each individual service. If bundled payments are used for service lines that require standby capacity, the payments would simply need to be priced at the marginal cost of delivering the bundle of services, rather than the average cost.4 For example, Medicare could use the standard DRG categories and weights to pay different amounts for inpatient admissions based on differences in the patient’s diagnoses and procedures, but the “conversion factor” would need to be lower than in the standard Medicare Inpatient Prospective Payment System, since the hospital would already be receiving Standby Capacity Payments for a portion of the costs that standard DRG payment amounts are supposed to cover.

If fees for individual services are based on the marginal costs of those services, the incentive to deliver additional services would be lower than under the current fee-for-service payment system, and so it would be less likely that use of bundled payments or case rates would create any significant savings. Although the financial risk to the hospital of a bundled payment will also be lower if the bundled payment is only intended to cover marginal costs, the bundled payment could still cause financial problems for a hospital with very small numbers of patients.

Accountability for Quality and Spending

The Need for Accountability by the Providers of Rural Care

In return for receiving adequate payments to support essential services, rural hospitals should take accountability for delivering appropriate, evidence-based services safely and efficiently. There are several reasons for this:

- It will be difficult to convince patients and private payers to pay more for services in rural areas without assurance that the higher payments will result in high-quality care.

- Because a significant portion of payments would no longer be tied directly to the number of services delivered, patients and payers will likely have concerns about whether access to services will decrease.

- It will be easier for payers to justify paying more for rural healthcare services if rural hospitals can help slow the overall growth in healthcare costs by improving the health of the residents of their community and reducing the delivery of unnecessary services.

Standard “Value-Based Payment” Approaches Should Not Be Used

The “value-based payment” systems currently used by Medicare and other payers in an effort to hold hospitals and physicians more accountable for quality and spending cannot and should not be used to create an accountability component in a Patient-Centered Payment system. Not only have these systems failed to encourage higher quality or lower costs, they are particularly problematic in rural communities because:

- the measures do not produce statistically valid results for many types of rural residents and patients. Small hospitals typically do not have enough patients to reliably use most outcome measures (e.g., mortality rates), and in many small rural communities, there may not be enough patients to reach minimal levels of statistical reliability even for some process measures. In addition, risk adjustment is based on diagnosis codes recorded on claims forms; diagnosis codes tend to be under-reported by rural providers, and they also fail to capture barriers to care such as distance from the hospital and lack of support services in the community, so rural hospitals can appear to have healthier patients or worse outcomes than they really do.5

- the measures do not clearly define the appropriate standard of care for individual patients. In many cases, providers are not really expected to achieve 100% success on a quality measure because the standard of quality is not applicable to all patients. However, most value-based payment systems do not permit providers to exclude patients from the measure even if the standard was inapplicable, so it is impossible to determine how many patients really don’t receive the care they need.

- the measures ignore the quality of care for the majority of patients. Many of the quality measures used in value-based payment programs focus on specific health problems such as diabetes or hypertension; there are no measures at all for patients with other kinds of health problems, and at most a few measures are designed for healthy patients. In a small rural community, there may not even be enough patients with common conditions to achieve minimum reliability levels on those measures (for example, only 11% of the total population and 27% of seniors have diabetes). As a result, the measures do not really assess the quality of care for the majority of patients.

- the measures ignore the need to maintain quality as well as improve it. Most quality measurement programs stop using quality measures if providers are able to routinely achieve them (so-called “topped out” measures). However, no longer using a measure allows that aspect of quality to worsen with no penalty, which is a particular problem in a payment system that is intended to encourage lower spending. The measures used to replace the “topped out” measures typically focus on aspects of quality where it is unclear what level of performance is feasible for providers to achieve, so providers are more likely to be penalized because of the types of patients they treat rather than the quality of care they deliver.6

- higher performance on the measures does not necessarily improve patient outcomes or achieve outcomes that are meaningful for patients. For many commonly-used measures, there is little or no evidence indicating that better performance on the measures will actually improve outcomes for patients, and in some cases, improving the measure can make patients worse off.7

- rural hospitals cannot control all of the key factors affecting the measures. Because a rural hospital provides only a fraction of all the healthcare services that residents of a rural community receive, the hospital only has limited influence over many aspects of quality and spending. For example, in several of its payment models, CMS plans to use the total hospitalization rate for patients as the principal way of assessing performance.8 However, this includes hospitalizations due to accidents and infectious diseases, inpatient procedures that patients chose to receive at other hospitals, and local hospital admissions to treat complications of services that were delivered by specialty physician practices at tertiary hospitals and complications of services at post-acute care facilities; none of these hospital admissions could be prevented or avoided by the local clinic or hospital.9

- the bonus/penalty structures attached to the measures have the potential to create significant financial harm for rural hospitals. Typical pay-for-performance systems reduce payments to hospitals based on whether their performance on the quality measures is above or below national averages or percentiles. However, the small number of patients in a rural community means that a rural hospital can easily be penalized simply due to random variation. Most hospital pay-for-performance systems reduce payments for poor performance but do not increase payments for good performance, so there is no way for the hospital to offset penalties that occur due to random variations.

Using Clinical Practice Guidelines to Assure High Quality Care in Rural Hospitals

Although it would seem desirable to assess the quality of care based on patient outcomes, outcomes are difficult to measure reliably with small numbers of patients, and small rural hospitals have less control over the factors that can affect outcomes for many types of conditions.

Clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) represent a more comprehensive, efficient, and patient-centered mechanism for achieving good patient outcomes than a list of quality measures. A clinical practice guideline assembles all of the available evidence regarding how to diagnose a symptom or treat a condition in a way that is likely to achieve the best outcome for each patient.10 Moreover, in contrast to the one-size-fits-all nature of quality measures, a CPG encourages and guides appropriate customization of services to patients with different characteristics based on available evidence.

Since clinical practice guidelines define which services are inappropriate as well as which services are appropriate, they can reduce use of unnecessary services in a more patient-centered way than burdensome and problematic prior authorization processes. In order to reduce variation, the guidelines can include a recommended option when there are multiple diagnostic or treatment choices and the available evidence does not indicate which option is better. The term “clinical pathway” is often used to describe a set of guidelines that recommend the use of a specific approach when the evidence is unclear or where multiple options have equivalent benefit.11

Clinical practice guidelines and pathways have been successfully used to improve quality and reduce variation in a variety of inpatient settings12. Studies have found that physicians would be willing to use guidelines if they are designed and implemented appropriately;13 in particular, physicians must have the ability to depart from the guidelines/pathway when there are good reasons to do so. For many types of patients, there is not strong evidence as to what approach to diagnosis or treatment would achieve the best result, so no guideline can dictate what should be done for every patient. In addition, the patient may be unwilling or unable to accept the services recommended by evidence, in which case a different set of services will be needed.

Accountability for Performance

In most value-based payment systems, performance is evaluated in terms of the percentage of times that a standard of quality was achieved for a group of patients, and future payments to the hospital are reduced if that percentage is lower than the percentage achieved by other hospitals or lower than some arbitrary threshold. This approach is problematic because:

- the hospital is still paid for delivering a service that failed to meet the standard of quality, and in most cases, that patient has to pay for a portion of that payment. It is of little comfort to the patient who received poor quality care that the majority of other patients received good care or that the percentage of patients who received good care was higher than at other hospitals.

- hospitals can receive no penalty at all even if a large percentage of patients fails to receive high-quality care, as long as most other hospitals provide equally poor care. Moreover, a hospital can be penalized for a low percentage score even though the quality measure was not applicable to many of the patients, since many quality measures do not allow patients to be excluded from the measure calculation even if delivering care in the way specified by the measure would harm the patient.

- the penalties result in the hospital being paid less for services delivered today based on quality problems that occurred in the past, even though the quality problems may have been eliminated in the interim. Reducing payments based on outdated performance information can jeopardize the ability to continue delivering high-quality care.

Businesses in other industries are not paid for their products and services in this way. They do not charge customers at all if the product or service they deliver is defective. That approach reduces the business’s revenue immediately rather in the future, and it ensures that the customer does not have to pay for a poor-quality product or service.

A similar approach can be used for rural healthcare services. If rural hospitals receive payments that are adequate to support the cost of delivering high-quality care, they should be able to follow evidence-based guidelines in delivering services, so there is no reason why they should be paid when they deliver a service to a patient that fails to meet those guidelines unless they can document the reasons for deviation.

Consequently, the hospital should only bill for delivering a service to a patient if it attests: (1) that it utilized Clinical Practice Guidelines appropriate for the patient’s problem(s), and (2) that it either (a) delivered services consistent with the guidelines or (b) documented the reasons for deviation in the clinical record (i.e., why the guidelines were inapplicable or inappropriate or that the patient had explicitly indicated that they were unwilling or unable to obtain the services consistent with the guidelines). For example, in order for the hospital to receive a Service-Based Fee for an Emergency Department visit, it would need to attest that it utilized Clinical Practice Guidelines appropriate for the patient’s symptoms and that it either (a) delivered diagnostic and treatment services consistent with the guidelines or (b) documented the reasons for deviation in the clinical record.

Since the Standby Capacity Payments are designed to ensure that services are available when needed, the hospital should be required to meet minimum standards of performance on access to services supported by those payments. For example, in order for the hospital to receive a Standby Capacity Payment for its Emergency Department, it would need to ensure that the ED responds in a timely fashion when patients need care. For example, it is reasonable to expect that every patient who comes to the ED should be seen in 30 minutes or less. If patient is not seen within 30 minutes, the hospital should not bill the patient’s insurance plan for a Service-Based Fee but it should also not receive a Standby Capacity Payment for that month.

Supporting More Comprehensive Improvement of Quality and Affordability

Although small rural hospitals can only be directly accountable for the quality of the services they deliver, this does not mean they should ignore the quality of healthcare services their residents receive from other healthcare providers, particularly since there may be ways that the hospital could redesign the care they deliver in ways that result in lower spending on those other services.

Examples of the types of quality/affordability improvement initiatives in which rural hospitals could potentially engage include:

- improving access to cancer screening for local residents;

- avoiding prescribing unnecessary, high-cost drugs;

- avoiding low-value testing for back pain and other common conditions;

- avoiding unnecessary specialist referrals and transfers to other hospitals for low-risk cases;

- improving access to behavioral health services and opioid use disorder treatment;

- prompt treatment for newly-diagnosed diseases.

In general, these improvements will not occur by including financial “incentives” in the payment system, but by providing adequate resources and assistance. In order for small hospitals to successfully engage in a more comprehensive approach to improving quality and reducing spending, they need to:

- know which opportunities for improvement exist in the community. The health problems of residents and the care delivery patterns of providers differ dramatically across the country. An improvement initiative that was successful in one community may have little impact in a different community, or pursuing it could divert time and resources away from another initiative that would have far more impact locally. Small rural hospitals do not have the capacity to pursue large numbers of initiatives, so they need to be able to prioritize their improvement efforts.

- have the capability to deliver care in different ways. There are relatively few situations in which outcomes are improved by simply stopping something that is currently being done; usually something different needs to be done – either a new service needs to be delivered instead of or in addition to an existing service, or an existing service needs to be delivered in a different way. Even if small rural hospitals begin receiving adequate financial support for the services they currently deliver, that does not mean they will have the resources necessary to deliver new services or to change the way they deliver current services.

Three things are needed to help rural hospitals identify and prioritize opportunities for improving the quality and affordability of healthcare for the residents of their communities and to implement successful improvement initiatives:

- Information on Services Delivered by Other Healthcare Providers. In most cases, rural hospitals only know about the services they deliver themselves, and they have little or no information about what other services their patients or the residents of the community are receiving from other providers either inside or outside the community, how much those services cost, etc. As a result, they have no way to identify opportunities for reducing total spending or redirecting their patients to higher-value sources of care. Since Medicare and health insurance plans do have these data, they should share both the data and analyses of the data with rural hospitals to help them identify opportunities for improvement and design interventions.

- Resources to Implement Changes in Care Delivery. In many cases, there are ways that a hospital could modify or expand its own services that would result in lower overall spending on healthcare services for the residents of the community, but the hospital does not have the resources to make those changes. To address this, hospitals should have the ability to design Performance Improvement Initiatives that define the results they believe they can achieve and the resources they need to do so. Medicare and other health insurance plans should then provide additional upfront payments to support the proposed changes in services, and hold the hospitals and clinics accountable for achieving the promised results.

“Shared Savings” programs do not provide the resources that rural hospitals need to successfully improve the quality and affordability of care. However, if – and only if – the rural hospital is receiving the kinds of information and resources to identify opportunities and implement changes described above, it would be possible to add an additional “Total Cost of Care” component to the Patient-Centered Payment. A Total Cost of Care component would provide a bonus payment to the hospital or clinic if:

- total risk-adjusted healthcare spending on the residents of the community or the patients of the clinic decreased by a statistically significant amount compared to previous years; or

- total risk-adjusted healthcare spending was lower than the majority of other communities or primary care practices and did not increase compared to previous years.

If such a Total Cost of Care component is added, it should be designed only to encourage and reward the hospital for reducing spending or maintaining low spending by identifying and successfully pursuing improvement initiatives, not to penalize it if spending is high or increases. It is impossible to design such a penalty in a way that avoids unfairly penalizing a small hospital for spending increases it had no ability to control, and that could harm both the hospital and its patients.

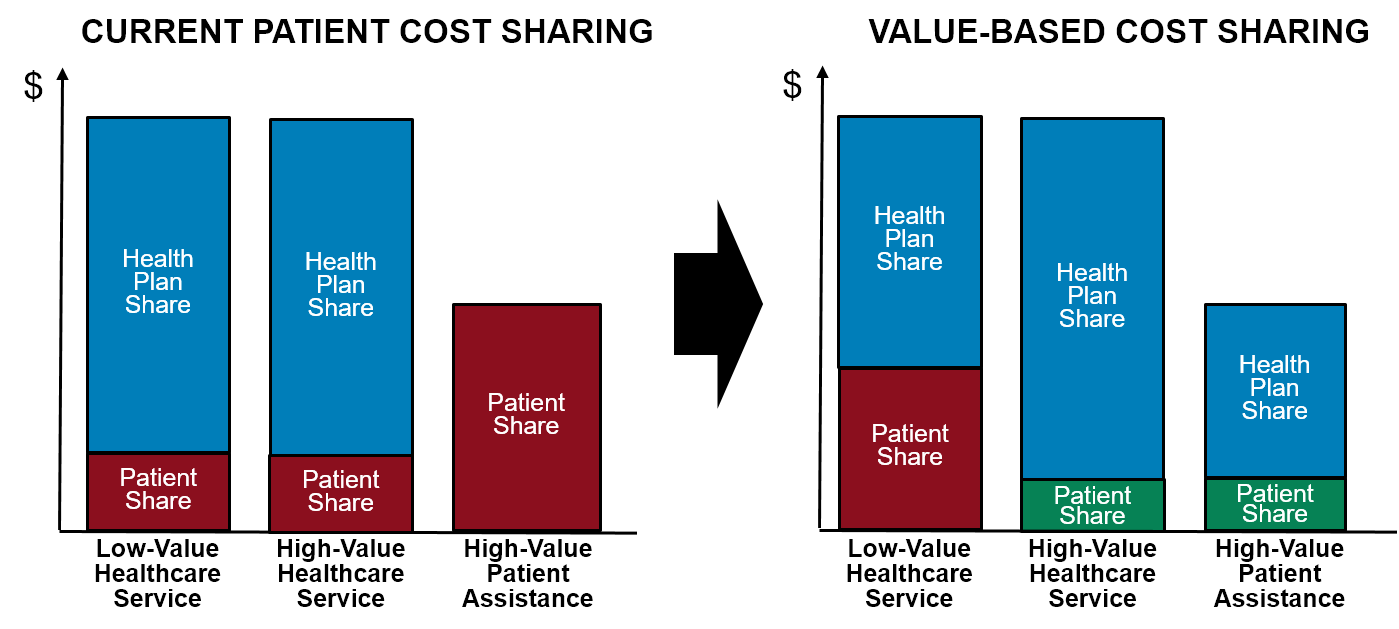

Value-Based Cost-Sharing for Patients

Medicare and most commercial health insurance plans require patients to pay a portion of the costs of most outpatient services they receive. Although cost-sharing is ostensibly intended to discourage unnecessary utilization of services by patients and to encourage them to seek out lower-cost services and providers, in many cases, cost-sharing merely shifts costs from insurers to patients and causes patients to delay or avoid receiving services they need. Moreover, a vicious cycle is created: to cover the costs of services when volume decreases, hospitals and clinics have to increase their charges, which means patients have to pay more for services, which further discourages patients from obtaining services they need, forcing even further increases in charges and causing worse outcomes for patients and higher spending for payers.

Cost-sharing will need to be structured in different ways in order to most effectively use Standby Capacity Payments and Service-Based Fees in place of traditional fees for services. The use of Standby Capacity Payments will result in a lower Service-Based Fee when a patient receives a hospital service, since the Fee will be based on marginal costs rather than average costs. However, if standard co-insurance percentages are applied to these lower fees, the amounts paid by patients could be so low that they encourage unnecessary utilization of the ED or laboratory tests.

It will be difficult to reduce the aggregate amount of cost-sharing contributed by patients for all of the services they receive from the hospital because that would require payments from insurance plans to increase even more than the increase that is already needed to adequately cover the cost of services. However, that aggregate amount of cost-sharing could be collected in different ways that better encourage the use of high-value services and discourage the use of low-value services than current cost-sharing systems do. At least two types of changes would be desirable:

- Flexibility to set lower cost-sharing rates for high-value services. Currently, patients are charged no cost-sharing at all for certain services designated as preventive care services in order to eliminate financial barriers to receiving those services, but patients are required to pay the same copayment amount or the same percentage co-insurance for every other service they receive. Instead, the hospital should be able to set lower cost-sharing amounts for additional types of services they want to encourage the patient to receive, e.g., regular lab testing to monitor a chronic condition. Similarly, the hospital should be able to set higher cost-sharing amounts to avoid encouraging the use of undesirable services; for example, the cost-sharing for a visit to the ED should be higher than the cost-sharing for use of the primary care clinic, so that patients do not have a financial incentive to use the ED as their source of primary care.

- Flexibility to provide non-healthcare services that assist patients in adhering to care plans. Even with lower cost-sharing amounts for individual services, patients who need multiple services may still face financial barriers in obtaining all of those services. Many patients also face financial barriers in obtaining healthcare services other than cost-sharing amounts. For example, even if there is no cost-sharing for a high-value service from the hospital, the patient may be unable to afford the costs for transportation or to take time off work in order to receive the service. To address this, hospitals should have the legal flexibility to use their own revenues to provide assistance to clients, and they should be able to seek additional funding to support this as part of a Performance-Based Initiative.

Figure 4

Comparison of Patient Cost-Sharing Under Current Systems and Patient-Centered Payment

Patient-Centered Primary Care Payment

Sustaining and Expanding the Other Essential Service – Primary Care

On the occasions when residents of a rural community experience a serious injury or a life-threatening illness, the most important healthcare service to have available in the community is a hospital with an Emergency Department and appropriate diagnostic and treatment services.

At all other times, however, the most essential service for residents of the community is effective primary care. Primary care is the only healthcare service that is specifically designed to help patients prevent health problems from occurring and to identify and treat new problems as early as possible so that outcomes will be better and treatment costs will be lower. Failure to provide adequate access to primary care in a community will result in poor health for residents, higher healthcare spending, and higher insurance costs.

The Problems with Current Visit-Based Payments for Primary Care Services

Current fee-for-service payment systems fail to provide adequate support for a small hospital ED because the hospital is only paid when a community resident visits the ED and it is paid nothing for the important service of standing by to serve other residents in case they have an emergency. Similarly, one of the reasons current fee-for-service payment systems fail to provide adequate support for primary care practices and clinics is that the practice is paid when a patient visits the practice to see a physician or other provider, but there is no payment at all if the practice succeeds in keeping the patient sufficiently healthy that the patient does not need to make visits. The primary care practice incurs the same costs to employ physicians, nurses, and other staff regardless of how many services patients happen to need, and the goal of primary care should be to keep patients healthy, not to deliver more services.

Moreover, fees for Rural Health Clinics and primary care practices have traditionally only been paid when the patient makes a face-to-face visit with a physician or other clinician at the practice, while nothing is paid for many other important services that are an integral part of good primary care, such as care management for patients who have a chronic disease, coordination of care for patients with multiple health problems, responding to patient questions and problems by phone or email, and proactively contacting patients to ensure they receive adequate preventive care. The only way primary care practices have been able to cover the costs of delivering all of these other services is to charge more for face-to-face visits. However, this penalizes a practice that uses the other services in ways that keep patients healthy and/or avoid the need for face-to-face visits, and it discourages patients from receiving care in a timely way. Even in the cost-based payment system Medicare uses for Rural Health Clinics, the payments are tied to the number of visits patients make, and so patients with greater needs will have to pay high cost-sharing amounts.

In recent years, Medicare and other payers have begun paying fees for specific types of care management and other services in addition to face-to-face office visits. During the 2020 coronavirus pandemic, Medicare and other payers began paying primary care practices for a broad range of telehealth services, i.e., visits conducted by videoconference or telephone. While these additional payments reduced some of the distortions associated with paying only for traditional face-to-face visits, narrow definitions of the services and mismatches between payments and costs have created new problems of under-utilization and over-utilization, and there is no guarantee that the payments will be continued.

Using Patient-Centered Primary Care Payment Instead of Only Visit-Based Payments

Every primary care practice delivers three important types of services to its patients:

- wellness and preventive care;

- chronic condition management; and

- non-emergency acute care.

A patient-centered payment system for Rural Health Clinics and primary care practices in rural communities should have separate payments for each of these types of services in order to ensure that each patient can receive the combination of services they need and want, and also to ensure that primary care practices with different types of patients can be paid adequately for the specific types of services they need to provide.

- Monthly Payments for Wellness Care. The most important role of primary care is to help patients stay healthy. Maintaining and improving health is a continuous process that occurs throughout the year, not simply through occasional office visits. Consequently, the Rural Health Clinic or primary care practice should receive a monthly payment for each patient who enrolls with the practice to receive wellness care management. (The monthly payment would support wellness care management; service-specific fees should continue to be paid for any specific procedures, tests, or treatments the patient needs as part of their wellness plan, such as immunizations, mammograms, colonoscopies, etc.)

- Monthly Payments for Chronic Condition Management. Some patients will have one or more chronic conditions, such as asthma, diabetes, or hypertension. If the patient wants the Rural Health Clinic or primary care practice (rather than a specialist) to help manage those conditions, the clinic/practice should receive an additional monthly payment for that patient in order to deliver chronic condition management services. Continuous, proactive care is needed to reduce the severity of symptoms and prevent exacerbations of the condition, so a monthly payment is necessary to support this.

- Higher payments for patients with a newly diagnosed or treated chronic condition. A higher payment will be needed during the initial month following diagnosis of a chronic disease because of the time required to develop a treatment plan that is feasible for the patient and to ensure it is effective.

- Higher payments for patients with a complex condition. A higher monthly payment will be needed for a patient with combination of chronic conditions or other characteristics that require the practice to provide significantly more assistance.

- A Fee for Diagnosis and Treatment of a Non-Emergency Acute Event. Some patients who are receiving good preventive care and chronic disease management will also have accidental injuries, acute illnesses, or problematic symptoms that will require additional services from the primary care clinic. Since these events will occur unpredictably, and different patients may be more susceptible to these problems than others, the Rural Health Clinic or primary care practice should receive an Acute Care Visit Fee when it provides diagnosis and treatment services for a new acute event. In contrast to current visit payments, however, the clinic/practice should be permitted to deliver the “visit” in whatever way is most appropriate in the circumstances, including by telephone, telehealth, or an in-person visit with the physician or other clinician. The Acute Care Visit Fee would not be paid to treat an exacerbation of a chronic disease, however, since the cost of that kind of care would already be covered by the monthly payment for chronic condition management.

Payments Based on Patient Enrollment

The Rural Health Clinic or primary care practice should only be paid for proactive wellness care and chronic condition management services if a patient wants to receive them. Not every patient may want wellness care assistance, and some patients with a chronic disease may need or want to receive support from a physician practice or hospital that specializes in the patient’s condition(s) rather than the Rural Health Clinic or primary care practice Consequently, the clinic/practice should only receive the monthly payments for these services for a patient who explicitly enrolls with the clinic/practice to receive them.

Enrolling with a clinic or primary practice to receive primary care services does not mean that the patient will need approval from that practice in order to receive specialty care services. The role of the clinic should be to help the patient receive the most effective services, not to serve as a “gatekeeper” for a health insurance plan. Moreover, a patient who does enroll should be able to disenroll at any time if they choose. This is easy to accomplish since the wellness care and chronic condition management payments are paid monthly.

Having the patient enroll with the Rural Health Clinic or primary care practice is far superior to the “retrospective statistical attribution” methods that Medicare and other payers have used in their primary care medical home programs. In these programs, primary care practices receive monthly payments either in addition to or instead of fee-for-service payments, but they only know if they will be receiving a monthly payment for a patient after the month has ended, and moreover, they only receive the payment if calculations by the payer show that the patient made more office visits to that practice than to other practices during some previous period of time. These attribution systems have been shown to assign the wrong patients to practices, and they also penalize practices who use the flexibility in the monthly payments to deliver services in ways that maintain and improve patient health without requiring as many in-person office visits.14 Because of these problems, Medicare has recently begun allowing primary care practices to enroll patients rather than relying solely on attribution methods.

Matching Clinic Revenue to the Cost of Meeting Patient Needs

A Rural Health Clinic or primary care practice that is caring for higher-need patients will need to have more staff in order to spend adequate time providing services to the patients, so it will need more revenue to pay for the cost of those staff. Although the current visit-based payment system provides more revenue for higher-need patients, that only happens if the patients receive care as part of visits at the clinic with clinicians, not if they receive education from a nurse or if a physician provides the help they need over the telephone. As a result, the more the clinic or practice invests in proactive care, telehealth, etc., the more money it will lose under the current system, particularly for the highest-need patients.

In contrast, Patient-Centered Primary Care Payment would provide the flexibility to deliver services in different ways and with different staff. The monthly payments would be higher for patients with chronic conditions and even higher for patients with complex conditions, and the payments for acute care visits would provide additional revenue for patients who do not have chronic conditions but have many acute health problems. This “risk adjusts” the clinic’s revenue based on three different characteristics of patients – their acute problems, their chronic conditions, and social factors that affect their health – whereas the standard risk adjustment systems used by Medicare and health insurance plans typically only adjust for chronic conditions. Although the “risk scores” assigned to each patient under standard risk adjustment systems might seem like a more precise approach to payment than simply stratifying payments into a few categories, the costs of delivering primary care do not change based on small differences in patient characteristics, so this level of precision is both unnecessary and problematic. Standard risk adjustment systems can penalize clinics whose patients have fewer but more severe conditions, and they create a financial incentive for the clinic to find more diagnoses to assign to a patient rather than to treat the patient’s health problems more effectively.15

Figure 5

Payments for Rural Health Clinics and Primary Care Practices Under Patient-Centered Payment

Higher Monthly Payments for Clinics That Provide a Broader Range of Services

Not all Rural Health Clinics and primary care practices provide the same types of services. For example, a growing number of primary care clinics are trying to provide behavioral health services as an integral part of the care they deliver to patients, while others still focus primarily on delivering physical health services and refer patients needing behavioral health services to another provider who is better qualified to deliver them. In a small community, the Rural Health Clinic may be providing maternity care, while a larger community may have a separate OB/GYN practice or birth center that delivers maternity care services.

A clinic that offers behavioral health services, maternity care services, or other specialized services will need to have appropriate staff and equipment to do so, and so its monthly costs will be higher. To address this, the clinic will need to receive higher monthly payments in order to support the higher costs. If the additional services are only delivered to a well-defined subset of patients, then it would be appropriate to define a separate, higher monthly payment category just for those patients.

Retaining Individual Fees for Selected Primary Care Services

Fees should continue to be paid for services delivered by Rural Health Clinics and primary care practices where there is a significant marginal cost to the clinic/practice associated with delivering the service. For example, administering vaccines to patients is a highly desirable service, but the Rural Health Clinic or primary care practice incurs significant additional costs to acquire and store vaccines, and the cost depends not only on how many patients are vaccinated but what type of vaccine they need and the current cost of that vaccine. Primary care clinicians can perform many types of procedures needed to treat injuries and other problems, but this requires them to have the necessary medical supplies and equipment to do so, and it would not be fair to charge all patients more for services that only a few patients will need.

Although it is appropriate to charge additional fees for these types of services, the fee for a service should be based on the time involved in delivering the service and any out-of-pocket costs the clinic incurs. This ensures the clinic does not lose money by delivering services patients need, while avoiding creating an incentive to deliver unnecessary services. In the case of drugs or medical supplies with unpredictable costs, it would be appropriate to reimburse the practice for its actual acquisition costs for the same reasons discussed earlier in the context of hospital services.16

In addition, if an individual does not want to enroll with the practice for ongoing wellness care or chronic condition management but that individual needs or wants preventive care or chronic care services, the practice should charge that patient’s insurance plan for the individual services instead of receiving a monthly payment for the patient.

Accountability for Quality

In order for a Rural Health Clinic or primary care practice to receive a monthly Wellness Care Payment or Chronic Condition Management Payment for a patient, the clinic would need to attest that the patient had received all evidence-based preventive care and chronic disease management services (or the patient was unable or unwilling to do so). If the clinic had not done those things for an individual patient, it should not bill the patient or their insurance plan for the monthly payment.

Although use of clinical practice guidelines will help ensure that patients receive evidence-based services during diagnosis and treatment, they do not directly ensure that patients are being diagnosed and treated when they need it. The physician and other staff at the hospital or clinic need to know that the patient is having a problem in order to have an opportunity to apply the guidelines in treating it. In addition, care providers need a way to know whether the patient is actually experiencing better outcomes as a result of the services that are delivered.

To address this, Rural Health Clinics and primary care practices should use a Standardized Assessment, Information, and Networking Technology (SAINT) to enable the practice to identify whether their patients are experiencing physical or emotional problems and whether the services provided by the clinic/practice are addressing the issues that are of most concern to the patient.17

How’s Your Health(www.HowsYourHealth.org){target=“_blank”} is a SAINT designed specifically for primary care that is easy and affordable to use, provides timely, actionable information to guide care, and enables and encourages patient participation. It generates the What Matters Index from patient-reported information on five issues:18

- Health Confidence: The patient’s level of confidence that they can manage or control most of their health problems.

- Pain: How much pain the patient has been experiencing recently.

- Emotional Problems: How much the patient has been bothered by emotional problems such as feeling anxious, irritable, depressed, or sad.

- Polypharmacy: The number of prescription medicines the patient is taking.

- Adverse Effects of Medications: Whether the patient is experiencing any side effects of their medications.

The What Matters Index has been shown to reliably identify patients who are at risk of hospitalization.19

Summary of Patient-Centered Payment

PATIENT-CENTERED PAYMENT

FOR RURAL HOSPITALS

1. Standby Capacity Payment for Essential Services

- A monthly Standby Capacity Payment is paid to the hospital by each health insurance plan for each of the plan’s insured members who live in the community served by the hospital.

- The amount of the Standby Capacity Payment should be set at a level such that the aggregate revenue (from all health plans providing insurance in the community) is sufficient to support the fixed cost of delivering essential services and maintaining appropriate standby capacity.

2. Service-Based Fees for Individual Hospital Services

- Health insurance plans also pay a fee when a community resident receives a service in an essential service line, with the amount of the fee based on the variable costs of delivering an additional service at the hospital.

- Health insurance plans pay fees for other services that are based on the average costs of delivering those services at the hospital. Health insurance plans that do not agree to make Standby Capacity Payments would have to pay fees for all services based on the hospital’s average cost of delivering the service.

- Health insurance plans reimburse hospitals for drugs and medical supplies based on their actual incurred cost.

3. Accountability for Quality and Efficiency

- Hospitals deliver evidence-based services safely and efficiently.

- Hospitals do not charge for a service if evidence-based Clinical Practice Guidelines were not followed and the reasons for deviation from the guidelines were not followed.

- Hospitals meet minimum standards for access and response time for essential services.

4. Value-Based Cost-Sharing for Patients

- Hospitals charge fees for services based on variable costs, not average costs.

- Hospitals have the flexibility to set lower cost-sharing rates for high-value services.

5. Patient-Centered Primary Care Payment for Rural Health Clinics

- Health insurance plans provide Rural Health Clinics and primary care practices with three new payments to replace traditional office visit fees for patients who enroll for wellness care or chronic condition management services.

- A monthly Wellness Care Payment to support proactive wellness and preventive care.

- A monthly Chronic Condition Management Payment for proactive care of patients who have a chronic disease.

- Acute Care Visit Fees for diagnosis and treatment of a new acute problem unrelated to a chronic condition.

- Health insurance plans pay Service-Based Fees when enrolled patients receive other primary care services, such as vaccinations and acute procedures.

- Health insurance plans pay traditional fees for services delivered to non-enrolled patients.

- Clinics follow Clinical Practice Guidelines to deliver evidence-based acute care, preventive care, and chronic disease management services.

- Clinics do not charge for a service if evidence-based guidelines were not followed and the reasons for deviation from the guidelines were not followed.

Examples of How Patient-Centered Payments Would Work

It is easier to understand the benefits of the Patient-Centered Payment System compared to global budgets, cost-based payment, and fee-for-service payments by examining how a hypothetical hospital or clinic would fare under the different scenarios about the volume of services and the cost of delivering those services discussed in other sections.

Patient-Centered Payment for Emergency Department Services

How Patient Centered Payments Could be Defined for a Hypothetical Hospital ED

The table below shows an Emergency Department at a hypothetical rural hospital (the staffing and other costs are described in more detail in . In the Status Quo scenario, the ED has 12,500 visits, and it is assumed to be serving a community with 25,000 residents. For purposes of this example, it is assumed that 5% of the residents are uninsured and that 5% of the ED visits are made by uninsured residents. It is further assumed that an additional 5% of the ED visits are made by non-residents of the community (e.g., visitors, non-residents who are working in the community, etc.).

Under the Patient-Centered Payment system, the payment amounts are assumed to be set as follows:

- The Standby Capacity Payment is set at an average of $100 per year for insured residents of the community (i.e., $8.33/month). This generates enough revenue to cover almost 75% of the cost of operating the ED, assuming participation by all of the health insurance plans used by the residents.20

- The fee charged for each ED visit made by a community resident is set at $65. (Separate payments would still be made for laboratory tests, drugs, etc.) The revenue from this fee would cover most of the remaining cost of operating the ED.21

- The fee charged for a visit made by a non-resident would be set at $325, which is more than enough to cover the average cost per visit.

With these payment levels, the hospital receives a small positive (3%) margin on the ED operations.

Figure 6

Patient-Centered Payment for Emergency Department Visits at a Hypothetical Rural Hospital

Impacts of Changes in Volume on Hospital Revenues and Margins

The table below shows the financial impact of changes in the number of ED visits.

- In Scenario A, the number of visits decreases by 10%, so revenues from visit-based fees decrease. However, most of the ED revenue is coming from the Standby Capacity Payment, not fees for individual visits, and the revenue from the Standby Capacity Payment is not affected by the number of services delivered. The reduction in visit fee revenue only reduces the total revenue by a small amount, so the ED breaks even, rather than experiencing a significant loss as it would under a purely fee-for-service or cost-based payment system.

- In Scenario B, the number of visits increases by 10%. Revenues from visit-based fees increase, but the revenue from Standby Capacity Payments stays the same, so there is a small increase in the margin, rather than the windfall profit that can occur under fee-for-service payment.

- In Scenario C, the number of visits increases significantly. The increase in the volume of visits is sufficiently high that the hospital needs to hire 2 additional FTE physicians in order to have two physicians on the high-volume shifts instead of one. The cost of operating the ED increases, but the hospital’s revenue also increases because it receives more visit-based fees. The net result is that the hospital’s profit improves slightly compared to the status quo scenario. In this scenario, it is assumed that most of the additional visits are made by non-residents (e.g., due to an increase in tourism), so the increased profit is generated by the non-resident visits.

Figure 7

Impacts of Changes in ED Visits Under Patient-Centered Payment at a Hypothetical Rural Hospital

STATUS QUO |

SCENARIO A Fewer Visits |

SCENARIO B More Visits |

SCENARIO C More Visits + Cost |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount | Amount | Change | Amount | Change | Amount | Change | |

| Service Area | |||||||

| Residents | 23,750 | 23,750 | 0% | 23,750 | 0% | 23,750 | 0% |

| Non-Residents | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Uninsured | 1,250 | 1,250 | 0% | 1,250 | 0% | 1,250 | 0% |

| Total Residents | 25,000 | 25,000 | 0% | 25,000 | 0% | 25,000 | 0% |

| ED Visits | |||||||

| Residents | 11,250 | 10,125 | −10% | 12,375 | 10% | 11,250 | 0% |

| Non-Residents | 625 | 562 | −10% | 688 | 10% | 3,000 | 380% |

| Uninsured | 625 | 562 | −10% | 688 | 10% | 750 | 20% |

| Total ED Visits | 12,500 | 11,250 | −10% | 13,750 | 10% | 15,000 | 20% |

| Revenue | |||||||