Global Budgets

The primary goal of most global hospital budget programs has been to reduce hospital spending, not to prevent closure of small hospitals. Although “global hospital budgets” have been proposed as a way of helping small rural hospitals, most global budget programs were created in order to limit or reduce payments to hospitals, not to address shortfalls in payment or prevent closure of small rural hospitals. Although Maryland’s global budget program has been cited as an example of how rural hospitals can benefit from this approach, the smallest rural hospital in Maryland closed in 2020 despite operating under the global budget system. Under the Pennsylvania Rural Health Model, hospitals receive global budgets that are based on the amount of revenues they received in the past, and there is no assurance the budgets will cover the current cost of delivering essential services. Under the CMS CHART Model, hospitals that participate would receive less revenue than they have received in the past, even if past revenues were insufficient to cover the costs of services.

Hospital global budget programs are far more complex than they seem. In Maryland, a state agency regulates the fees each hospital is paid for each individual services, and it uses complex formulas to establish an annual budget for each hospital. The hospital has to adjust its service fees during the year in order to stay within the budget, unless the state approves a modification to the budget. In Maryland, all payers are required to pay the hospital the fees approved by the state, including Medicare and Medicaid.

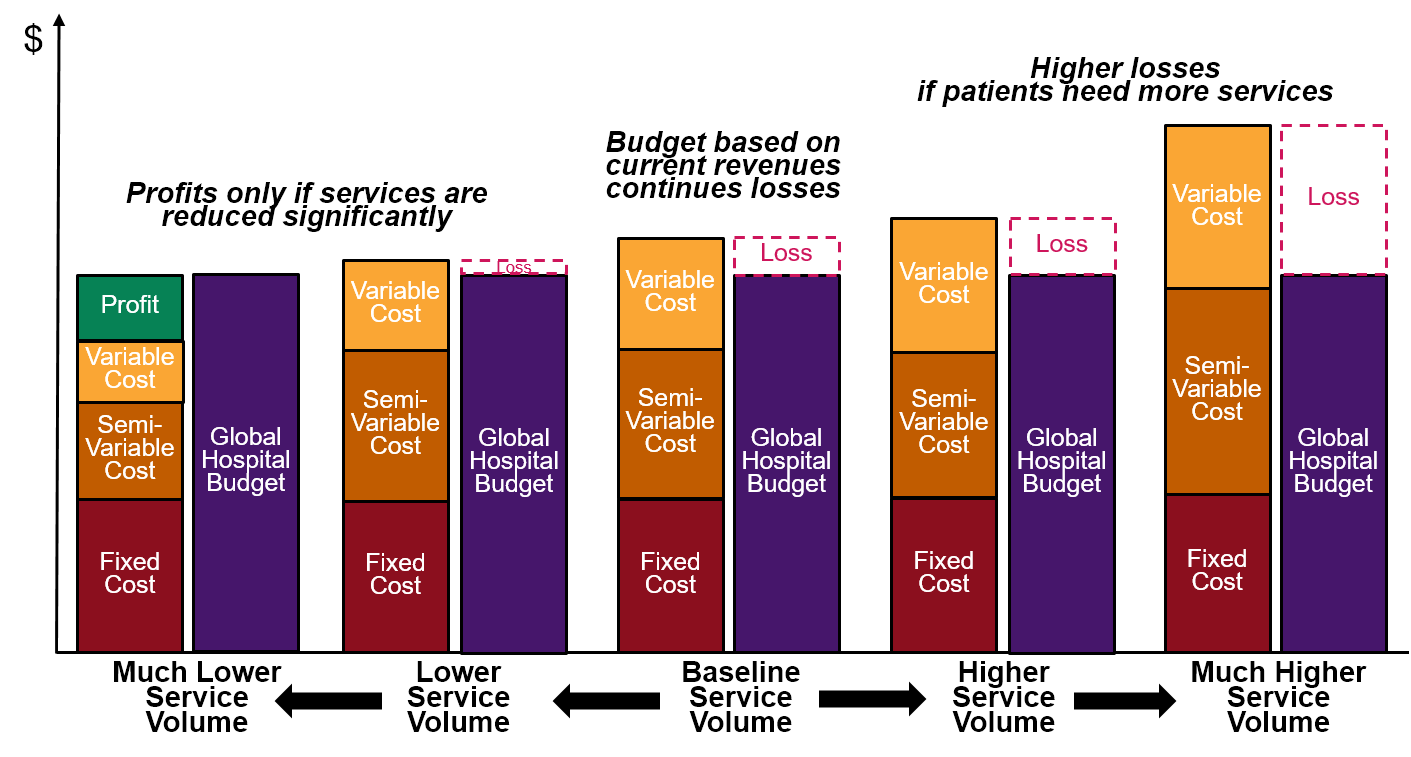

Some rural hospitals could benefit from a global budget program in the short run, but most would likely be harmed financially. Hospitals in communities that are experiencing significant population losses or that deliver unnecessary services could benefit from a global budget program, at least in the short run, because revenues would no longer decrease when the volume of services decreases. However, hospitals that experience higher costs or higher volumes of services due to circumstances beyond their control would likely be harmed, since their revenues would no longer increase to help cover the additional costs.

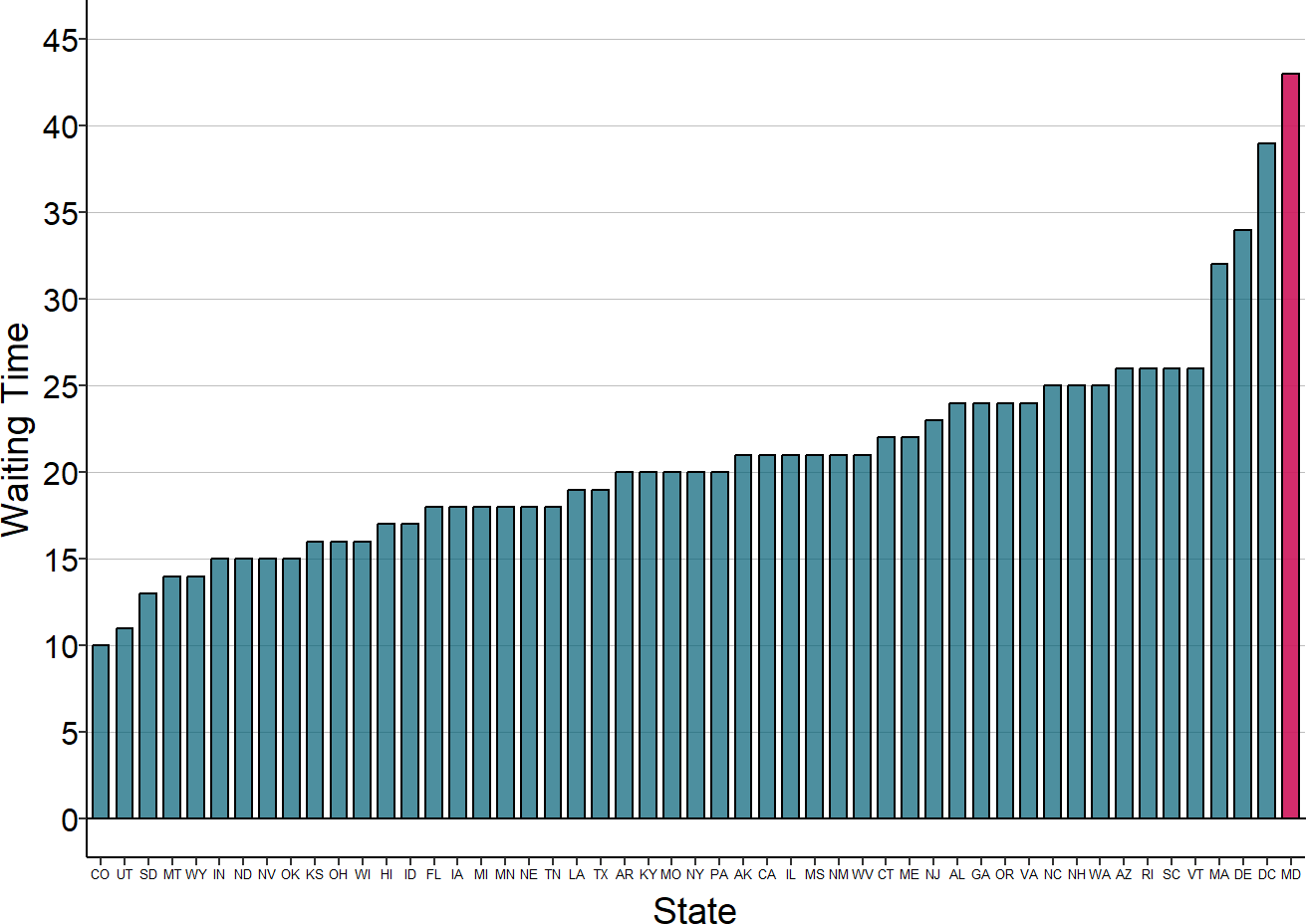

Access to care for patients could be harmed by a global budget. Under a global budget, a hospital receives the same amount of revenue regardless of how many services it delivers. This can result in delays in patients receiving the services they need. For example, after implementation of global budgets, Maryland had the longest emergency department wait times of any state in the country.

Other countries have moved away from using global budget systems. Global hospital budgets have been used for many decades outside of the U.S. However, because of concerns about long waiting times for services, many countries have modified or replaced global budgets with “activity-based” payment systems, similar to some of the fee-for-service payment systems used in the U.S.

The Concept of a “Global Budget” for a Hospital

Over the past several years, there has been growing discussion about using “global budgets” as a way of reducing financial problems for rural hospitals and preventing closures. Under a global budget, a hospital’s revenue is no longer based on the number of services that it delivers, so the hospital will not lose revenue if it delivers fewer services because of either a decline in population in the local community, improved health of the residents, or reluctance of residents to obtain services during a pandemic.

Although various forms of global budgets for hospitals have been used in a number of other countries for decades, they have been used only rarely in the United States. However, the State of Maryland now requires the use of global budgets for all hospitals in the state, and the CMS Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) has funded a demonstration project in Pennsylvania under which several hospitals are receiving a portion of their payments based on a global budget model. Interest in global budgets increased in 2020 because many hospitals experienced significant reductions in revenue due to the lower volume of elective healthcare services during the coronavirus pandemic, and some or all of those revenue losses could have been prevented if the hospitals had been paid through a global budget. In August 2020, CMMI announced the “Community Health Access and Rural Transformation (CHART) Model;” the CHART “Community Transformation Track” includes a component in which hospitals in up to 15 regions can receive payments under a global hospital budget model.

In contrast to fee-for-service payments and cost-based payments, there is no standard way of defining a global budget or paying a hospital based on one. The impact of a global budget on a small rural hospital will depend heavily on the details of how the budget is designed, and also on the size and characteristics of the community the hospital serves. The approach being used in Maryland is very different from the approaches being used in Pennsylvania and in the CHART Model, and all three of those are different from the payment models used for hospitals in other countries. Importantly, the primary goal of the global budget programs both in the U.S. and other countries has been to limit or reduce the amount of spending on hospitals, not to reduce financial losses and prevent closures of small, rural hospitals.

Global Budgets in Maryland

How Global Budgets Work in Maryland

Since 2014, no hospital in Maryland has been permitted to receive more revenue for inpatient and outpatient services during a year than the amount of “Approved Regulated Revenue” the state has approved in advance. This revenue amount is determined through the state’s Global Budget Revenue program and is commonly referred to as the hospital’s “global budget.”

The global budget in Maryland is, in fact, a budget, not a payment. A hospital in Maryland is still paid a fee for each individual service it delivers by the individual health insurance plan that insures the patient who received the service. The way the hospital stays within the budget is by changing the amounts of the fees that it charges for individual services. If the hospital’s revenue exceeds its budget, it must cut the fees that it charges for individual services. If the hospital’s revenue falls short of its budget, it is permitted to increase its fees to make up the difference.

Maryland can ensure that a hospital receives no more and no less than the global budget amount because the state has a power no other state has – it regulates the fees that hospitals charge for inpatient and outpatient services and every payer is required to pay the hospital those fees. This includes payments for services delivered to Medicare beneficiaries, because Maryland is the only state in the country that has been given authority by Congress to determine the amounts that the Medicare program will pay for hospital services in the state.

As a result, if a hospital has to charge more for services in order to get the full amount of revenue specified in the global budget, all health insurance plans, Medicaid, and Medicare must pay the higher fees. Conversely, if the hospital needs to cut its fees in order to stay within the budget, the state can require that it do so. A hospital is permitted to increase or decrease its fees by up to 5% during the year in order to stay within the budget, and it can increase or decrease fees by as much as 10% if it receives approval from the state to do so. If the hospital’s actual revenue during the year ends up being higher or lower than the approved budget, then the hospital’s fees have to be increased or decreased during the following year to make up the difference.1

In contrast to other states, where there are typically large differences in the amounts paid for the same service by Medicare, Medicaid, and different health insurance plans, in Maryland, all payers pay essentially the same amount for each individual service.2 Moreover, the amounts payers pay are set at levels the state views as sufficient to cover the hospital’s cost of caring for uninsured patients.

Both fees for individual services and the global budget amounts are determined by the Maryland Health Services Cost Review Commission (HSCRC), an independent state commission led by 7 gubernatorially-appointed commissioners. The Commission was created in 1971 and it has been setting hospital rates for both Medicare and private payers since 1977. The Commission sets rates for 47 acute general hospitals, 3 specialty hospitals, and 3 psychiatric hospitals. It has over 40 staff, and its budget is funded through an assessment on hospitals rather than through general state tax revenues.3

The HSCRC only regulates the prices of inpatient and outpatient hospital services. It does not control the amounts that physicians and other providers are paid for the services they deliver, nor does it regulate other services that hospitals offer. The formal name for the global budget is “Approved Regulated Revenue” because only the revenue for the services whose prices are regulated by HSCRC is included.

The History and Goals of the Maryland Global Budget System

Maryland’s global budget system was not created to solve financial challenges facing small or rural hospitals in the state. The state’s rate regulation system already allowed it to ensure that a hospital received enough revenue to cover its costs, since the state could authorize rate increases that all payers would have to pay.

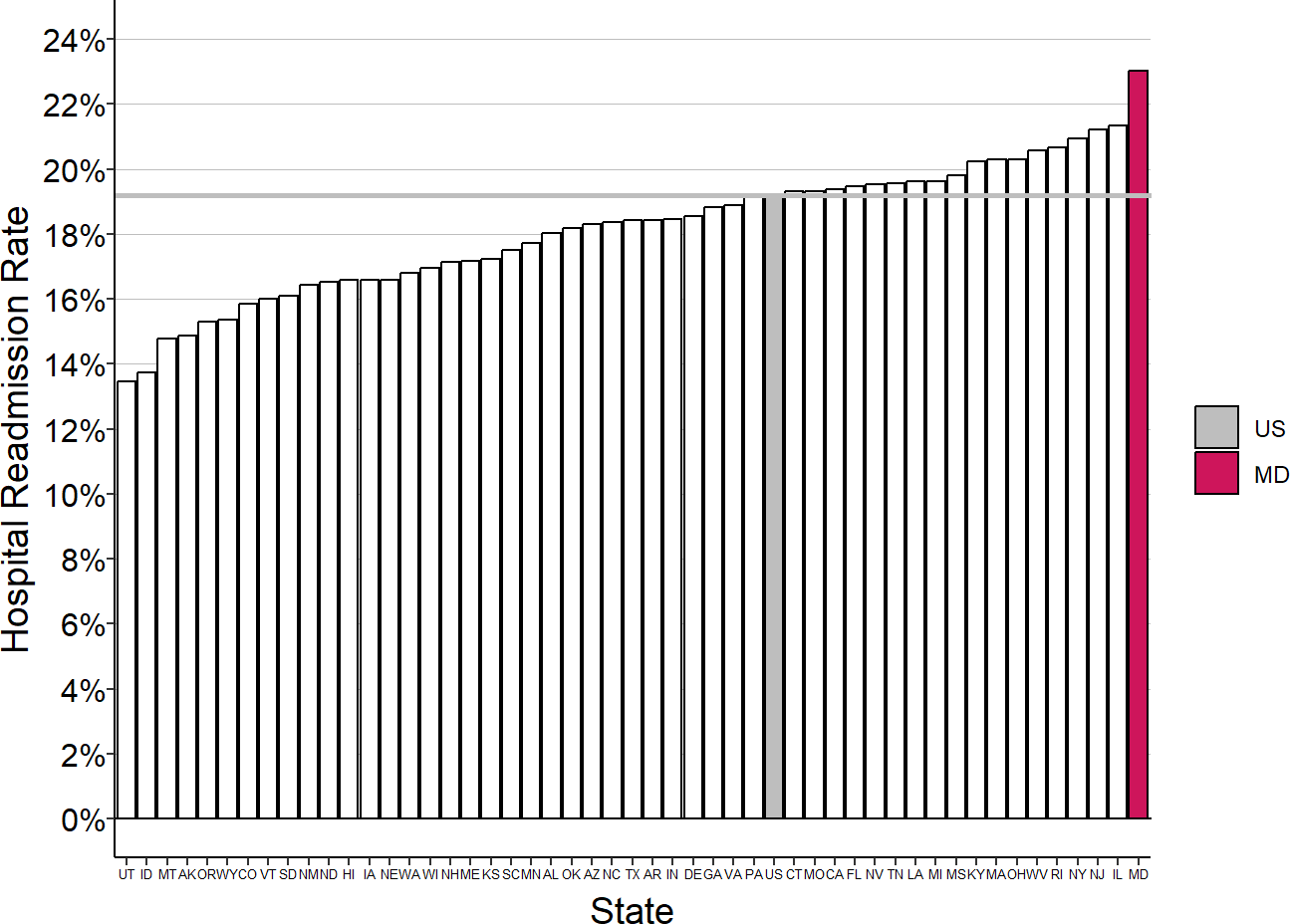

The problem Maryland was trying to address was over-utilization of hospital services. Maryland had the highest rate of hospital readmissions for Medicare beneficiaries in the country in 2010, and it also had one of the highest rates of hospital admissions. The global budgets were explicitly intended to serve as a “revenue constraint and quality improvement system” to “provide hospitals with strong financial incentives to manage their resources efficiently and effectively in order to slow the rate of increase in health care costs and improve health care delivery processes and outcomes.”4

Figure 1

Medicare Hospital Readmission Rates by State, 2010

Source: Medicare Geographic Variation Public Use File. US=National average.

Hospitals in Maryland, like those in every other state, were paid based on how many hospital admissions they had, so they were financially penalized if they reduced avoidable hospital admissions and readmissions. Maryland’s rate regulation authority gave it the ability to eliminate that penalty by allowing a hospital to charge more for services when utilization decreased. However, doing this threatened to violate the terms of the federal waiver that allowed the state to set Medicare payment amounts. The federal waiver was conditional on payments per admission for Medicare beneficiaries in Maryland increasing at a slower rate than the amounts Medicare paid in the rest of the country. Even if total Medicare spending on hospital admissions in Maryland decreased because the number of hospital admissions decreased by more than the payment per admission increased, the state’s waiver was based solely on how much the Medicare payment per admission increased.

To avoid this, Maryland entered into a revised agreement with CMS in 2014 that held the state accountable for controlling Medicare spending on hospital services per beneficiary rather than the amount spent per admission. Under what was known as the Maryland All-Payer Model, in return for the continued ability to set hospital payment rates for Medicare, Maryland agreed to do the following things over a 5-year period:

Limit annual all-payer per capita inpatient and outpatient hospital cost growth to the previous 10-year average annual growth in gross state product (3.58%).

Generate $330 million in “savings” to Medicare based on the difference in the Medicare per-beneficiary total hospital cost growth rate between Maryland and that of the nation overall.5

Reduce the 30-day readmission rate to the unadjusted national Medicare average.

Reduce the rate of potentially preventable complications by nearly 30 percent.

Limit the annual growth rate in per-beneficiary total cost of care (TCOC) for Maryland Medicare beneficiaries to no greater than one percentage point above the annual national Medicare growth rate in that year.

Limit the annual growth rate in per-beneficiary TCOC for Maryland Medicare beneficiaries to no greater than the national growth rate in at least 1 of any 2 consecutive years.

Submit an annual report demonstrating performance on various population health measures.

How Global Budgets in Maryland Are Set

The process of setting global budgets for each hospital in Maryland is very complex. In order to encourage reductions in hospitalization and to satisfy the terms of the new Medicare waiver, a multi-step process is used to determine the global budget for each hospital. Each year, the HSCRC determines a new budget for a hospital using the following factors:6

the amount of the hospital’s global budget in the previous year;

inflation in costs of drugs, supplies, and wages;

the hospital’s performance in improving quality, reducing readmissions, reducing hospital-acquired conditions, and reducing other types of potentially avoidable utilization;

changes in the amount of uncompensated care at the hospital;

changes in insurance coverage in the state that affect utilization of services;

changes in the size and composition of the population served by the hospital;

unanticipated events that significantly increase utilization of hospital services (e.g., a natural disaster or epidemic);

changes in the hospital’s market share among Maryland residents (but only for services that are not deemed to represent “potentially avoidable utilization”);

changes in the number of out-of-state residents using a hospital’s services;

the hospital’s efficiency in delivering services relative to other hospitals;

shifts in the delivery of services to unregulated settings (e.g., ambulatory surgery centers or physician practice offices);

transfers of patients from one hospital to another;

amounts the hospital is required to pay the state under various tax/assessment programs;

the variance between actual and approved revenue in the prior year;

the extent to which the state has generated the total amount of statewide savings in Medicare spending promised as part of the state’s agreement with CMS;

the growth in total hospital spending in Maryland relative to the state economy; and

changes requested by the hospital to support new service lines, capital needs, etc.

Not only is the overall process complex, the calculations for many of the individual steps make it even more complex. For example, the budget is adjusted for changes in the population of the hospital’s service area using a Demographic Adjustment Factor determined through a complex series of steps.

(.)

A Virtual Patient Service Area (VPSA) is defined for each hospital based on the communities where the hospital’s patients live. In more rural areas, the VPSA is defined in terms of counties, whereas in the rest of the state, it is defined in terms of zip codes.

Each hospital is assigned a portion of the population of the VPSA as follows:

For each hospital, the number of Equivalent Case Mix Adjusted Discharges (ECMADs) is calculated for six separate age cohorts (0-14, 15-54, 55-64, 65-74, 75-84, and 85+) in each county or zip code in the VPSA. The ECMAD includes both inpatient and outpatient services; outpatient visits are converted to equivalent inpatient discharges using the ratio of average inpatient charges per discharge to the average outpatient charge per visit. The case mix adjustments are determined for inpatient charges using the 3M APR-DRG grouper and for outpatient charges using the 3M EAPG (Enhanced Ambulatory Outpatient Groups) grouper.7

In each VPSA, estimates are made of the number of residents in each of the six separate age cohorts for the base year and the current year.

The hospital is assigned a proportion of the base year population in each age cohort and county/zip code based on the number of ECMADs the hospital delivered to residents of that county/zip code in that age cohort relative to the total ECMADs delivered by all hospitals to residents of that county/zip code in that age cohort. For example, if there are 1,000 individuals ages 55-64 living in zip code X, if there were 20 Equivalent Case Mix Adjusted Discharges of 55-64 year-old residents of zip code X at all hospitals in the base year, and if Hospital A delivered 10 of those discharges, then Hospital A would be assigned 50% (10/20) of the 1,000 55-64 residents in zip code X.

The hospital’s assigned population in each age cohort and each county/zip code in the VPSA are summed to determine the hospital’s total base year service population.

The age-adjusted population growth rate for the hospital’s service population is determined as follows:

A relative cost weight is determined for each age cohort by taking the total statewide hospital charges per capita for patients in each age cohort and dividing by the total statewide hospital charges per capita for all ages. For example, if the average total charge per patient for patients age 55-64 is 1.5 times the overall average charge per patient, then the age 55-64 cohort is assigned a weight of 1.5.

In each age cohort in each county/zip code, the percentage growth in the number of residents between the base year and the projection year is estimated.

The population growth rate in each age cohort and county/zip code is multiplied by the relative cost weight for that age cohort and county/zip code. For example, if the number of 55-64-year-olds living in a particular zip code is estimated to have increased by 10% and the cost weight for 55-64-year-olds is 1.5, then the adjusted growth rate for that age cohort is 15%.

The adjusted growth rate in each age cohort and county/zip code is multiplied by the hospital’s assigned population in that age cohort and county/zip code, and the products are summed over all age cohorts and counties/zip codes in the VPSA and divided by the hospital’s total base year service population to determine the hospital’s age-adjusted projected population-related growth.

A Demographic Adjustment Factor for the hospital is determined from the age-adjusted population growth rate for the hospital’s service area as follows:

The percentage of the hospital’s revenue that is determined to have resulted from Potentially Avoidable Utilization (PAU) is calculated. PAU is determined by using computer programs to examine each of the hospital’s discharges and outpatient services and categorize them as either PAU or not. This includes:8

30-day, all-cause, all-hospital inpatient readmissions, excluding planned readmissions;

Prevention quality indicator overall composite measure (PQI #90) as defined by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) except for PQI 02 (Perforated Appendix) and PQI 09 (low birth weight);

65 potentially preventable conditions (PPCs) determined by 3M software; and

Outpatient rehospitalizations in the emergency room or observation occurring between 1 to 30 days of an inpatient admission.

The hospital’s age-adjusted population growth rate is reduced by the PAU percentage. For example, if the hospital’s age-adjusted population growth rate is 5% and if 20% of the hospital’s revenue was determined to be potentially avoidable, the growth rate would be reduced to 4%.

An “efficiency adjustment” may then be applied to this rate if the PAU/age-adjusted growth rates for all hospitals would result in total statewide hospital spending that exceeds the overall target population increase allowance. For example, if the total statewide increase in hospital spending would be 2% but the target growth rate is 1%, then a 50% efficiency adjustment would be applied to every hospital’s PAU/age-adjusted rate to determine its final Demographic Adjustment Factor.

Since many patients will have a choice of two or more hospitals for some or all of the services they need, adjustments have to be made to hospital budgets if patients begin using different hospitals for their services. A complex methodology is used to distinguish an increase in a hospital’s market share from an increase in the number of services the hospital delivers to the same patients; the key steps are:

The number of inpatient and outpatient services that each hospital delivers to patients living in a specific zip code or county is determined. The number of admissions is calculated separately for each of 47 service lines (defined by groups of APR-DRGs), and the number of outpatient services is calculated separately for 11 different service lines.

Any inpatient or outpatient services that are determined to represent Potentially Avoidable Utilization are excluded from the totals. This is designed to avoid giving a hospital credit for treating a patient who may not have needed the service and to avoid penalizing a hospital for not treating such a patient. In addition, a series of highly-specialized services such as organ transplants are excluded.

The growth in volumes at hospitals with utilization increases is compared to the decline in volumes at hospitals with utilization decreases. The lesser of the total volume gains and losses is determined, and each hospital then receives its relative proportion of that total.

The Impact of Maryland’s System on Small Rural Hospitals

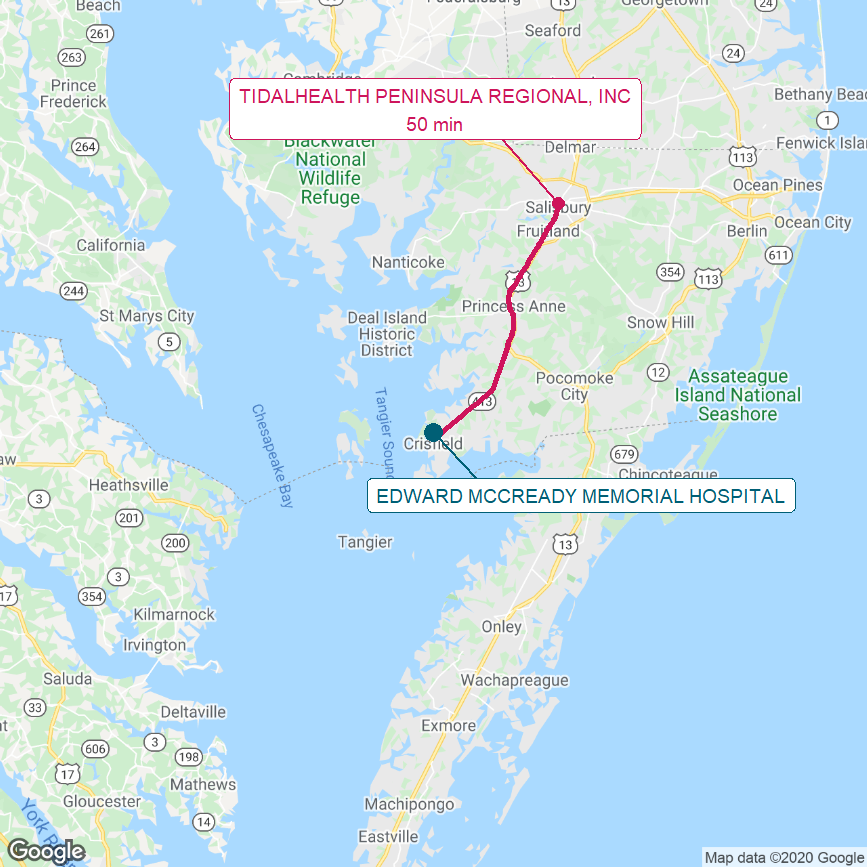

Figure 2

Edward W. McCready Hospital, Maryland

Map shows the Lower Eastern Shore of Maryland. The red line shows the most direct driving route from McCready Hospital to the next-closest hospital and the estimated travel time.

Maryland has no Critical Access Hospitals, and it had only one rural hospital that was as small as the hospitals discussed in The Causes of Rural Hospital Problems – the Edward W. McCready Memorial Hospital, located in the town of Crisfield on Maryland’s Lower Eastern Shore.

In 2019, McCready Hospital had total operating expenses of $17.8 million and an average daily acute census of 1.9 patients. It was the only hospital in Somerset County, Maryland and served a population of about 7,000. The next closest hospital is the Peninsula Regional Health System in Salisbury, which is a 50-minute drive from Crisfield.

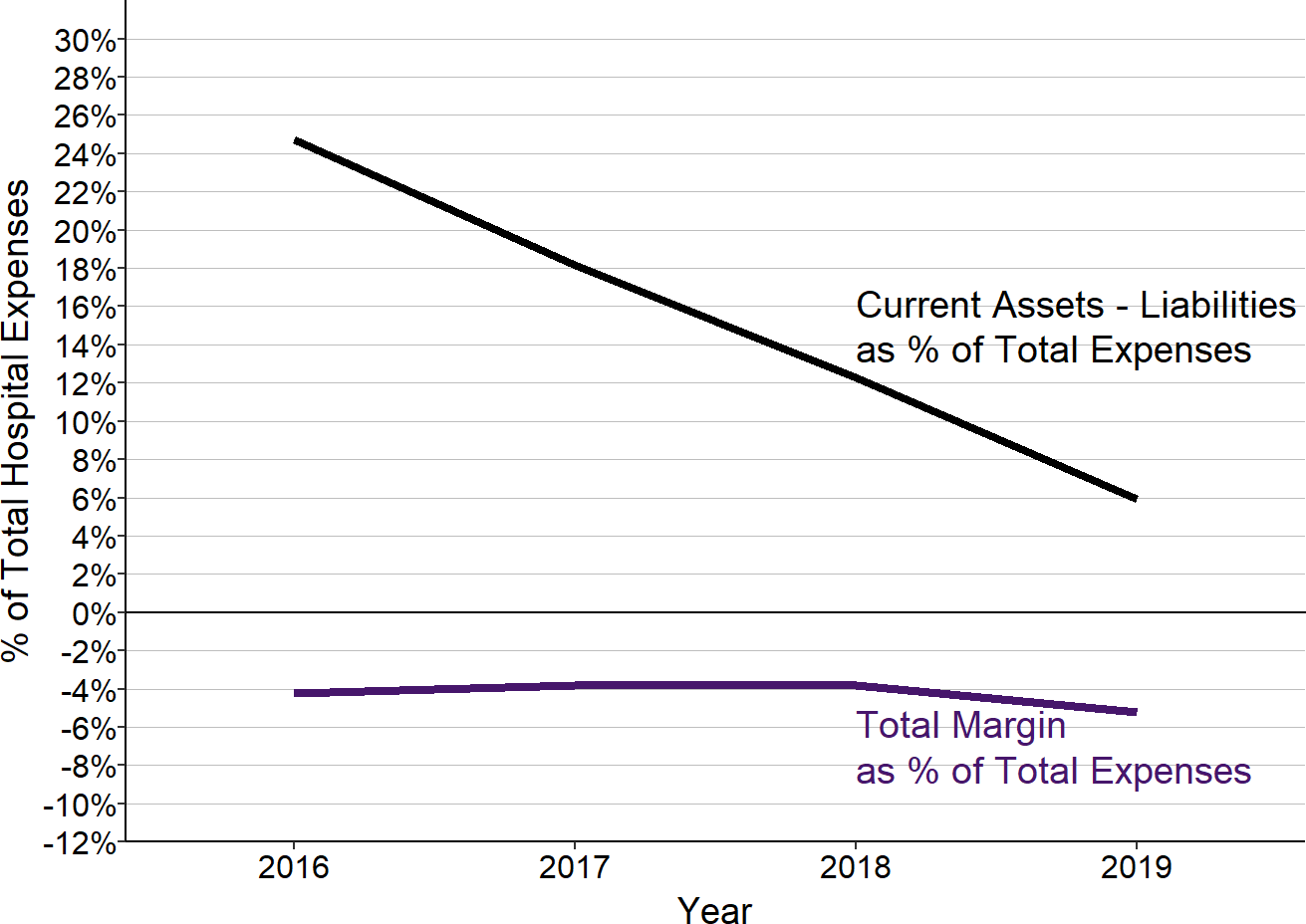

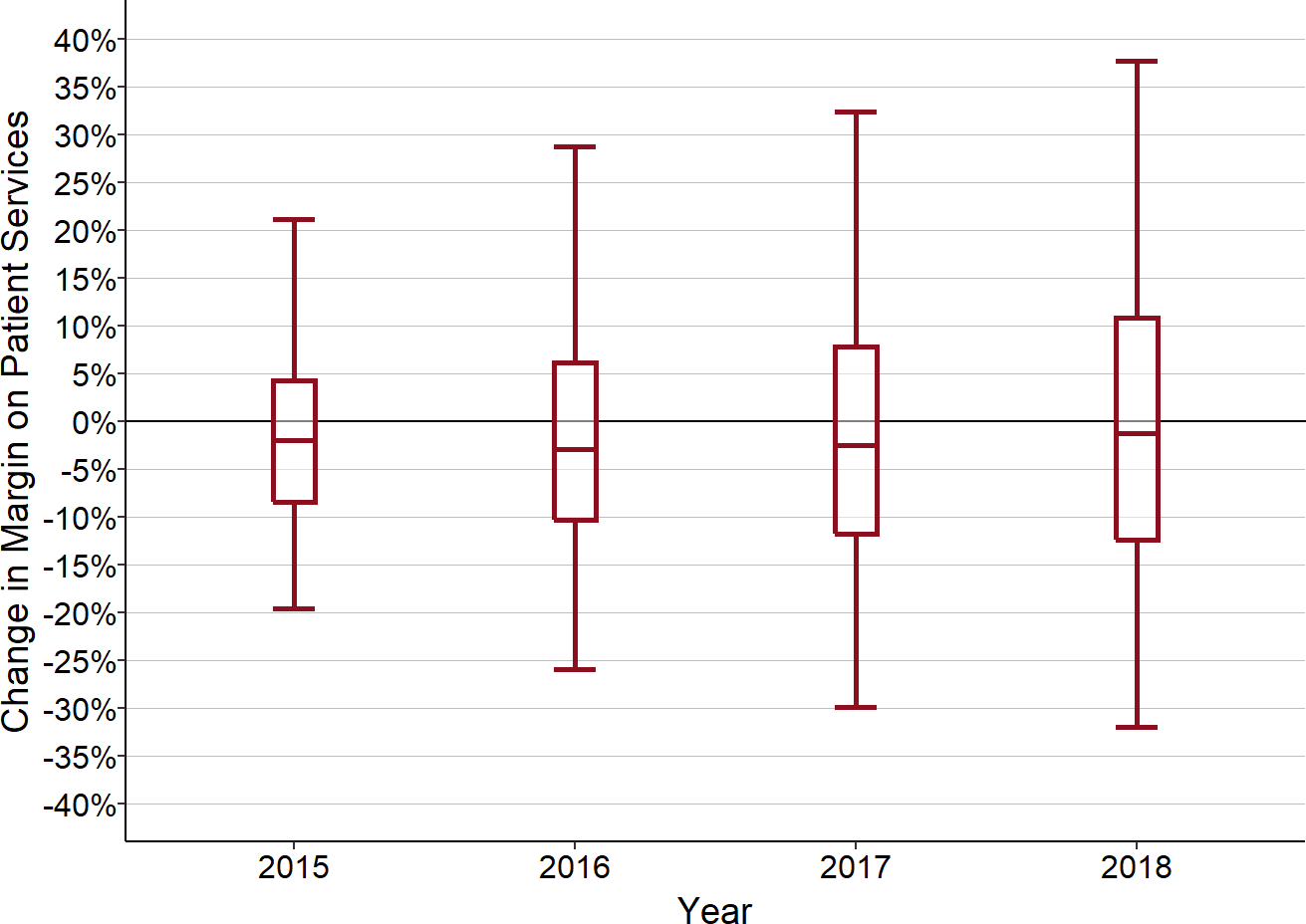

Despite participating in the global budget program, McCready Hospital lost money every year from 2015 to 2019. Losses were about -4% from 2016-2018, and then increased to more than -5% in 2019, and the hospital’s current net assets (current assets minus current liabilities) decreased every year as a result.

Figure 3

Total Margin and Net Current Assets Prior to Closure

Edward W. McCready Hospital, Maryland

McCready Hospital closed in 2020.

Because of the losses, McCready was forced to close as a free-standing hospital in 2020. Peninsula Regional Health System, which operates Peninsula Regional Medical Center (the largest hospital on the Eastern Shore with 266 beds) and Nanticoke Memorial Hospital (a 139-bed hospital in Seaford, Delaware), acquired the hospital’s facilities and it has stated that it plans to continue operating the emergency department and primary care clinic and providing laboratory/imaging services at the same site until it builds a new outpatient facility several miles away. Inpatient and surgical services will no longer be delivered in Crisfield.

A 2017 case study9 describing McCready Hospital stated that the HSCRC rate setting process was a “complicated and lengthy negotiation” that was “rarely finalized by the start of the fiscal year when it takes effect” and required hiring a consultant for “guidance in completing the complex rate-setting worksheet.” The case study noted that because of the impact of utilization variability on the hospital’s margins, the hospital staff had to continuously review revenues in order to make adjustments in fees to stay within the global budget, and because of the hospital’s small size, it was difficult to make fee changes that would offset changes in utilization. In a year when the hospital experienced significant and unexpected growth in the volume of surgeries, the state reportedly worked with the hospital to increase the global budget. Moreover, changes in fees made during the year in order to stay within the global budget meant that patients could pay different amounts for the same test during the same year. The case study also reported that McCready Hospital was able to open an urgent care center in a town 14 miles away because revenue from services delivered there would not be included under the global budget.10

The Impact of Maryland’s System on Larger Rural Hospitals

Almost all of the hospitals in Maryland are in urban areas. Only five of the hospitals that have participated in the global budget program were located in a rural community, and the smallest of those (McCready Hospital) closed in 2020. The four rural hospitals that are still open are large in size relative to rural hospitals in other parts of the country; all of them have more than $45 million in total annual expenses, and one spends over $200 million per year. However, despite participating in the global budget program, all but the largest hospital had operating losses in 2019.

Several studies11 have examined the impact of the Maryland global budget system on “rural hospitals,” but five of the eight hospitals examined in these studies are actually large hospitals that are not federally-designated as rural hospitals, while three of the six Maryland hospitals that are located in a rural area were not included in the analyses.12 The eight hospitals in these studies are those where HSCRC implemented its initial version of the global budget methodology (the Total Patient Revenue system, or “TPR”) in 2010. The TPR hospitals are described as “rural” by HSCRC because each is the only hospital located in its community; HSCRC began implementation of global budgets at these hospitals because there was less need to make adjustments for changes in hospital market share than in areas that have multiple hospitals. Two of the other rural hospitals in the state (including the smallest hospital, McCready Hospital) began participating in a global payment arrangement with HSCRC before 2010, and the studies excluded those two from the analyses because of that.

The TPR hospitals are much larger and deliver far more inpatient care than most rural hospitals in other states. The median acute census of the TPR hospitals is 55, whereas the median number of acute patients in rural hospitals nationally is only 6. The median total expense of the TPR hospitals was over $165 million, over four times the median of $36 million for rural hospitals nationally.

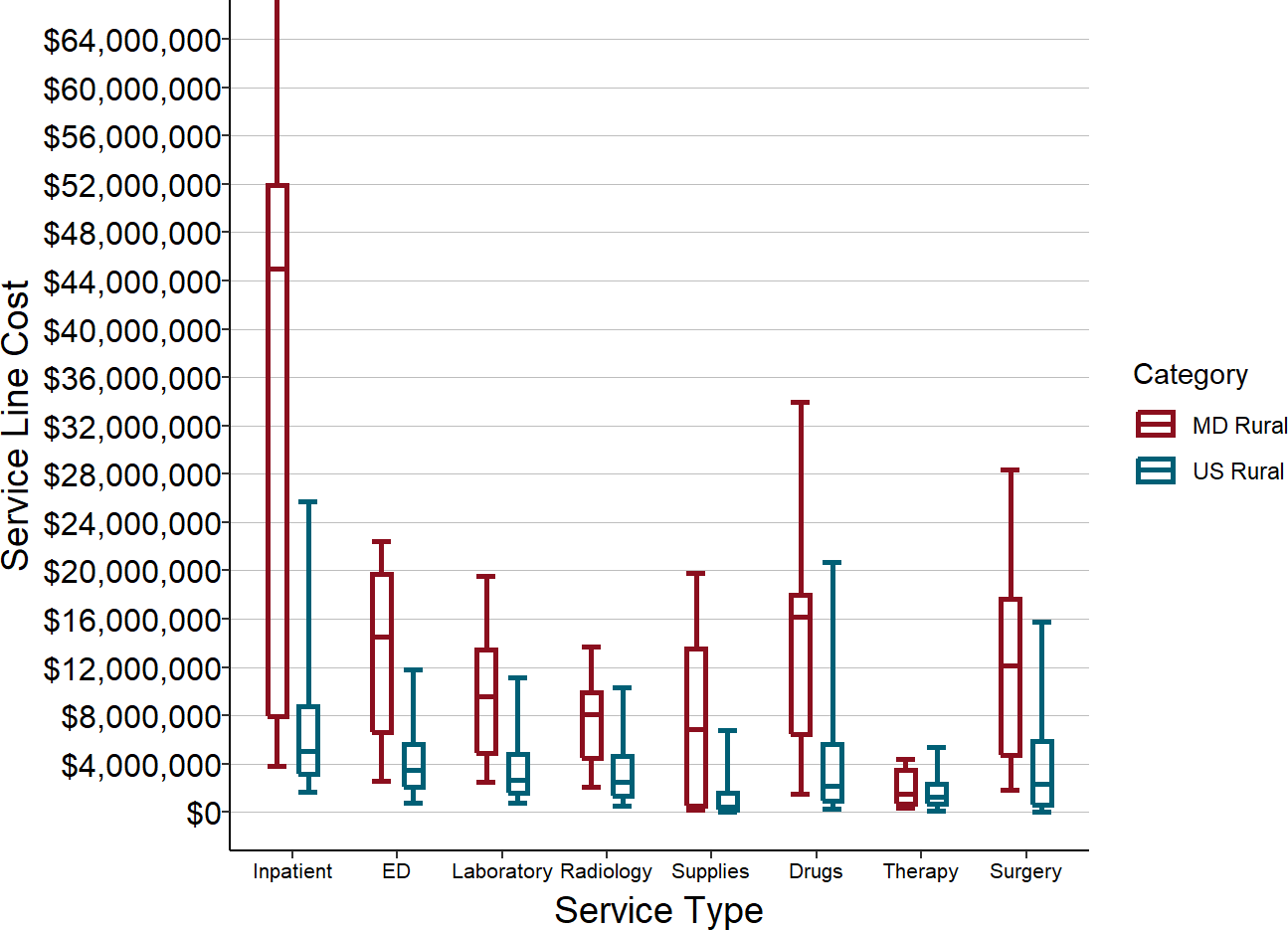

As shown below, expenses in all of the core service lines are much higher at the Maryland “rural” hospitals than they are at most rural hospitals in other states. The difference is particularly large for inpatient care, which is consistent with the fact that Maryland has had much higher rates of hospital utilization than other states. However, this difference means that the Maryland hospitals had much bigger opportunities to reduce inpatient admissions and spending than rural hospitals in other states would have, and the financial losses at the hospitals from such reductions would be much greater in Maryland than in other states in the absence of the global budget system.

Figure 4

Service Line Costs in Maryland TPR Hospitals

and U.S. Rural Hospitals

Values shown are median costs for the most recent three years available. TPR = Maryland Total Patient Revenue

Since the primary goal of creating the global budgets was to encourage reductions in unnecessary hospital admissions and outpatient services, the primary focus of all of the studies has been determining whether the number of services delivered at the hospitals increased or decreased. Three of the studies13 found there was no reduction in hospital admissions or readmissions at the TPR hospitals compared to similar hospitals that were not participating in the global payment arrangement, but a fourth study found that inpatient admissions decreased.14 Three of the studies found large reductions in outpatient services such as clinic visits and surgeries, but no significant change in Emergency Department visits.15 However, all of these studies only examined changes during the first few years after the global budgets and none examined changes in utilization or spending after 2013.

In 2014, the global budget program was expanded to include all hospitals in Maryland. CMS conducted an evaluation of the impacts of the overall program that examined changes in utilization and spending through 2018.16 This study found that there had been reductions in spending on hospital care and overall healthcare services for Medicare beneficiaries, but not for commercial insurance patients. While the study found there were reductions in inpatient admissions for Medicare, Medicaid, and commercial insurance patients, the reductions were only statistically significant for Medicare patients. The study authors reported that they did not find any consistent differences in the impacts for rural vs. urban residents, but they defined “rural” as living in non-metropolitan areas, which included urban areas as well as rural areas.

The Impact of Maryland’s System on Patient Access to Services

One of the principal concerns about a global budget system is whether it will be more difficult for a patient to obtain services. If a hospital’s revenue is no longer tied to the number of services it delivers, then it no longer experiences any financial penalty if patients are denied services or if they have to wait to receive them, and it no longer has the ability to generate the additional revenue needed to pay for expanded service capacity.

Many countries that have used global budgets for hospitals have national systems for monitoring the amount of time that patients have to wait to receive services, but the U.S. has no such system because there have not been concerns about delays in service under fee-for-service or cost-based payment systems.

As part of its Hospital Compare program, CMS used to collect information on the amount of time patients spend waiting to be seen in Emergency Departments and it still collects information on the amount of time patients who need to be admitted wait in the ED for a hospital bed. The data show that patients in Maryland waited longer to be seen in the ED than in any other state in 2017. In addition, patients in Maryland who needed to be admitted had a median wait of over 6 hours for a hospital bed, the second highest of any state.17

Figure 5

Median Time Spent Waiting in ED Before Being Seen, 2017

Source: Average by state from CMS Hospital Compare. Red bar is average for Maryland

The evaluation of the Maryland model conducted by CMS did not look at the issue of wait times for services. The study found that patients reported their experience in Maryland hospitals was worse than patients reported for comparison hospitals on nearly every experience measure examined, but the experience measures in Maryland did not worsen under the global budgets. The study did find that Medicare beneficiaries were more likely to obtain services from physicians’ offices than from hospital outpatient departments after the global budgets were put in place.18

The Pennsylvania Rural Health Model

The History and Goals of the Pennsylvania Rural Health Model

The Pennsylvania Rural Health Model was a demonstration project that was created in 2017 by the CMS Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) specifically for rural hospitals in Pennsylvania. It was designed to test whether paying rural hospitals a fixed, predetermined amount for all hospital-based inpatient and outpatient services (i.e., a “global budget”) will enable the hospitals “to invest in quality and preventive care, and to tailor their services to better meet the needs of their local communities.”19 The demonstration ended at the end of 2024.

The Pennsylvania Rural Health Model was not designed to increase payments to rural hospitals in order to eliminate or prevent financial losses; in fact, it was required to reduce the total amount that Medicare spends on hospital services for Medicare beneficiaries who live in the communities served by rural hospitals. This included both the Medicare payments to the rural hospitals under the global budget and payments to any other hospitals that provide services to the residents of the rural hospital’s service area, regardless of where those other hospitals are located. Pennsylvania was expected to achieve a cumulative total of $35 million in Medicare savings on hospital services for residents of the rural hospitals’ service areas by the end of the project. “Savings” were calculated by comparing what Medicare actually spent on hospital services to a projection of what would have been spent if spending had increased at the rate that Medicare hospital spending increased in rural areas nationally. In addition, the project was monitored to determine whether Medicare spending on all services, not just hospital services, has increased more than in other states.

In order to receive the global budget payments, hospitals were required to prepare a “Rural Hospital Transformation Plan,” which had to be approved by both the state and CMMI. CMMI provided $25 million in grant funding to the state to create a Rural Health Redesign Center Authority to oversee the program, but there was no funding for the individual hospitals.

The Pennsylvania Rural Health Model (PRHM) was not a permanent program. Changes in Medicare payment ended after the 6-year period.

The hospital global budgets were originally supposed to begin in January 2018, but due to difficulties in recruiting hospitals to participate, the first hospitals did not begin participating until 2019. The Pennsylvania Rural Health Redesign Center Authority was supposed to be established by January 2018, but the Pennsylvania General Assembly did not enact the enabling legislation until November 2019.

How Global Budgets Worked in Pennsylvania

The global budgets used in the Pennsylvania Rural Health Model worked very differently from those in Maryland:

Budgets were Payer-Specific, not truly “Global.” In Maryland, hospitals have a single global budget for their inpatient and outpatient revenue from all payers, and each payer’s share of the budget may differ from year to year depending on how many of that payer’s members received services during the year and what kinds of services they received. In Pennsylvania, a hospital had a separate budget amount for each payer, and there was no requirement that those budgets change in proportion to the relative numbers and types of services received by each payer’s insured patients.

Hospitals Received Periodic Budget Payments, Rather Than Fees for Services. In Maryland, hospitals continue to get paid fees for individual services; the global budget is a mechanism for forcing the fee amounts to increase or decrease so that total revenue stays within the global budget amount. In Pennsylvania, Medicare and participating payers no longer paid fees to a participating hospital for individual services delivered; instead, they paid the hospital a predetermined amount regardless of the number of services the hospital delivered to patients insured by that payer.

Pennsylvania Had No Authority to Ensure Budgets Are Adequate to Support Costs of Services for Insured and Uninsured Patients. In Maryland, the HSCRC has the power to regulate the amounts that every payer, including Medicare, pays each hospital for its services, and it can use that power to ensure that a hospital’s total revenue is adequate to support the costs of services, including the costs of serving uninsured patients, and that each hospital receives revenues equal to its global budget. Although the Pennsylvania Rural Health Redesign Center Authority was supposed to determine what the global budgets for hospitals should be, it could not force Medicare or any health insurance plan to pay hospitals based on those budgets.

Not All Pennsylvania Hospitals Were Eligible to Participate. In contrast to Maryland, where all hospitals are required to participate in the global budget system, participation in the Pennsylvania Rural Health Model was limited to hospitals in counties designated as “rural” by the Center for Rural Pennsylvania.

Participation by Hospitals in Pennsylvania was Voluntary. Whereas all hospitals in Maryland are required to be paid under a global budget, participation in the Pennsylvania Rural Health Model was voluntary, and continued operation of the program was contingent on a minimum number of hospitals agreeing to participate. The agreement between CMMI and Pennsylvania required that a minimum of 6 hospitals participate in the program during the first year and that a minimum of 18 hospitals participate during the second year. However, only 5 hospitals agreed to participate in the first year and only 13 hospitals signed up for the second year (2020), even though a total of 67 hospitals were eligible to participate (two of the eligible hospitals closed since the program was first created). Four additional hospitals agreed to participate in 2021.

Participation by Payers in Pennsylvania was Voluntary. In Maryland, all payers are required to participate in the global budget structure, but payer participation in the Pennsylvania Rural Health Model was voluntary. Not all commercial plans in the state participated, including several large national payers. The agreement between CMMI and Pennsylvania required that at least 90% of hospitals’ revenues come from payers who are participating in the program, but no information has been released as to whether that has happened.

Patient Cost-Sharing Was Not Controlled in Pennsylvania. Maryland regulates the amounts paid by all payers, which includes the prices charged to individual patients who do not have insurance; moreover, by regulating the prices charged to insurance companies, Maryland also indirectly controls the cost-sharing amounts paid by insured patients. However, in Pennsylvania, the amounts that Medicare and other payers paid the hospital under the global budget represented only the insurer’s share of the payment for services. The hospital still billed for individual services, and patients were still required to pay their share of those bills –patients without insurance were responsible for 100% of the hospital’s charge, and patients with insurance were responsible for the cost-sharing required under their insurance plan.

Because of these differences, the impacts of the Pennsylvania Rural Health Model on hospitals, patients, and payers were very different from the impacts seen under the Maryland system. For example:

In Pennsylvania, a hospital’s total revenue would still increase or decrease based on changes in the volume of services delivered to patients whose insurance plans are not participating in the model. If a hospital delivered fewer services to these patients, the hospitals would experience financial losses.

In Pennsylvania, a participating payer could unilaterally reduce the size of its global budget at a hospital regardless of whether patients were receiving fewer services, and it could refuse to increase the size of the budget even if the hospital’s costs had increased for reasons beyond its control. A payer whose membership decreased in the community served by a hospital could decide to reduce the budget amount it contributed, while a payer that had an increase in membership could refuse to increase its contribution. These kinds of changes could lead to financial losses at participating hospitals.

In Pennsylvania, a hospital could still increase its total revenue by increasing the amounts it charges patients for services, since there is no global budget for the revenues the hospital receives directly from patients. Pennsylvania does not regulate the prices hospitals charge, and an insurance plan participating in the global budget program would no longer have any reason to negotiate the amounts paid for individual services because the insurance company is paying the same amount in total regardless of what the hospital charges for individual services. Consequently, patients could pay significantly more for services than they did prior to use of the global budget regardless of whether the volume of services decreases.

In Pennsylvania, if patients began going to non-participating hospitals to receive services instead of participating hospitals, the hospitals delivering the services would receive more revenue, since those hospitals would be paid through standard fees for services.20 Since the Pennsylvania Rural Health Model was required to limit the growth in total Medicare hospital spending, an increase in the number of services delivered at non-participating hospitals would mean that the global budgets at the participating hospitals had to be reduced, potentially causing financial losses for the hospitals.21

In addition to the above differences, the Pennsylvania Rural Health Redesign Center Authority was funded entirely with federal funds under a grant from CMMI, whereas the HSCRC in Maryland is funded through an assessment on the hospitals in the state. Although the Pennsylvania General Assembly enacted legislation creating the Pennsylvania Rural Health Redesign Center Authority, it did not appropriate any state funds to support it nor did it provide any other mechanism for it to generate funding. Consequently, there is no assurance that it will continue operating after the federal grant funds run out.

How Global Budgets in Pennsylvania Are Set

In the first year that a hospital participated in the Pennsylvania Rural Health Model, its global budget payment from Medicare was determined using a simple formula. The global budget was supposed to be equal to the greater of: 1) the hospital’s Medicare revenue from the most recent fiscal year for which complete claims data are available or 2) the average of the revenue in the three prior years. Although there was a presumption that a similar methodology will be used by other payers, there was no requirement that they do so.

Even if a hospital had been losing money with current fee-for-service or cost-based payment amounts, there was no explicit provision for increasing the initial global budget amount to ensure it is adequate to cover the cost of delivering services at the hospital. The presumption was that the flexibility provided by the global budget would enable the hospital to modify its services in some fashion to reduce its costs without harming the quality of care for patients.

Most payment model demonstrations developed by the CMS Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation have set the initial payment amounts for participants at a level below the amount they would otherwise have expected to receive in order to produce savings for the Medicare program. Presentations by CMMI about the global budget concept in Pennsylvania indicated that some kind of “discount” would be applied to the global budget payments, either initially or after several years, in order to reduce spending for payers, so depending on the amounts and timing of these reductions, they could potentially create financial losses for hospitals that had not had losses to date and they could increase current losses rather than reduce them.

In subsequent years, the hospital’s global budget amount for Medicare was to be determined by adjusting the prior year’s budget for inflation, demographic shifts, service line changes, shifts in patient volume between hospitals, the hospital’s performance on quality measures and population health outcome measures, expected reductions in potentially avoidable admissions, and other factors. However, no details on how these adjustments were made have been publicly released, so it is unclear whether and how it will differ from the Maryland methodology.

There was a provision in the Pennsylvania Rural Health Model for increasing a hospital’s global budget amount from Medicare in later years if (1) there had been a reduction in Medicare’s total spending for patients living in the hospital’s service area and (2) the overall program had been successful in achieving at least two of three population health goals: a) increasing access to primary and specialty care, b) reducing rural health disparities through improved chronic disease management and preventive screenings, and c) decreasing deaths from substance use disorder and improving access to treatment for opioid abuse. However, there was no explicit mechanism for increasing the global budget amount to provide the participating hospitals with additional resources to achieve those goals. Here again, there was an implicit presumption that the flexibility provided by the global budgets would enable participating hospitals to reallocate their resources in a way that would result in better outcomes.

Hospital Participation in the Pennsylvania Rural Health Model

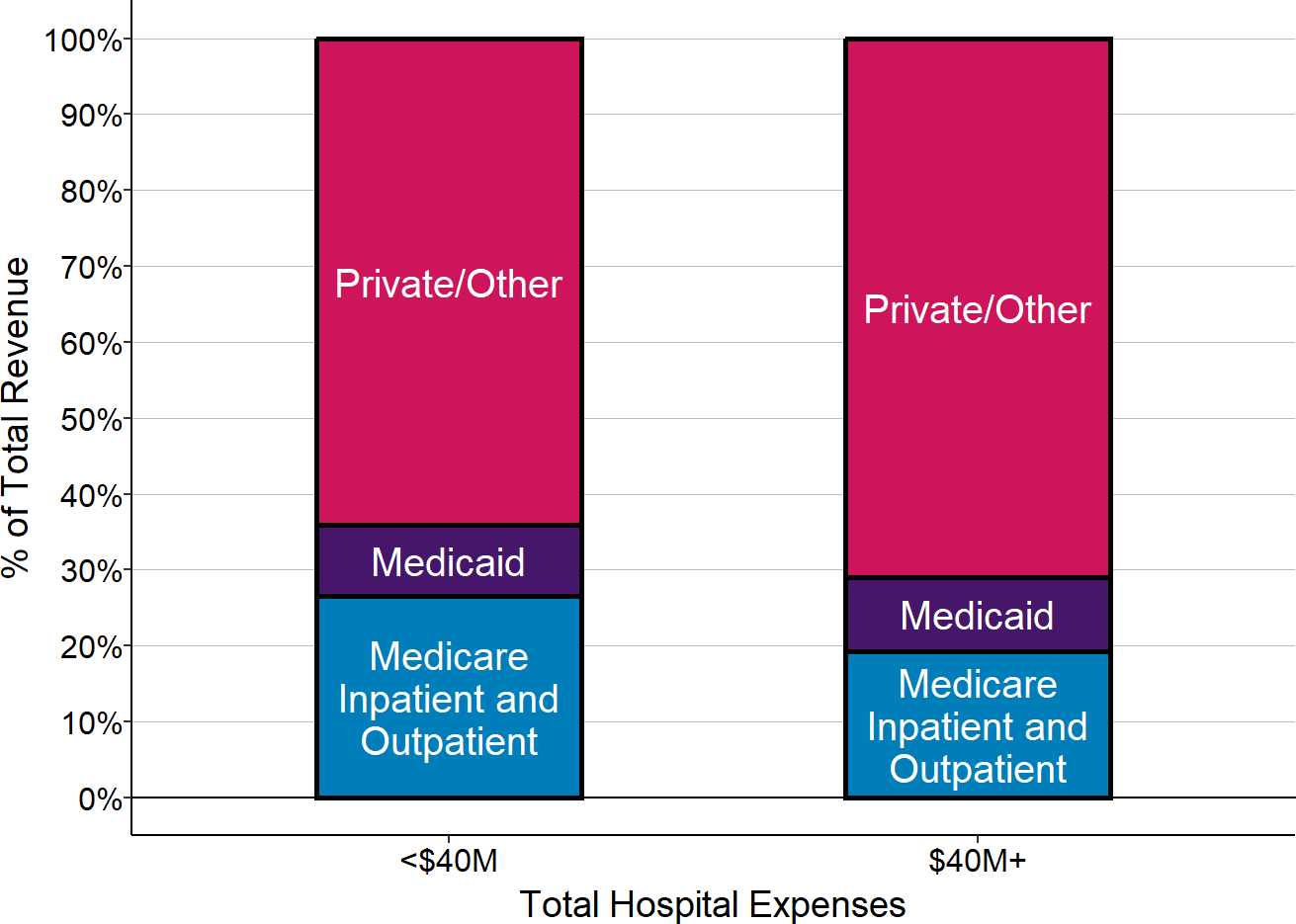

Most of the hospitals that agreed to participate in the Pennsylvania Rural Health Model were not small, rural hospitals. Because the program defines “rural” differently than other federal programs, nearly one-third (5) of the 18 hospitals participating were not classified as rural hospitals under standard CMS or HRSA definitions, and some hospitals that were classified as rural under federal standards were not eligible to participate in the Pennsylvania program. Of the participating hospitals that were located in rural areas, two-thirds had total expenses of more than $45 million, and one-third had total expenses of $100 million or more. Only 4 hospitals were the kinds of small rural hospitals that are having the most serious problems nationally.

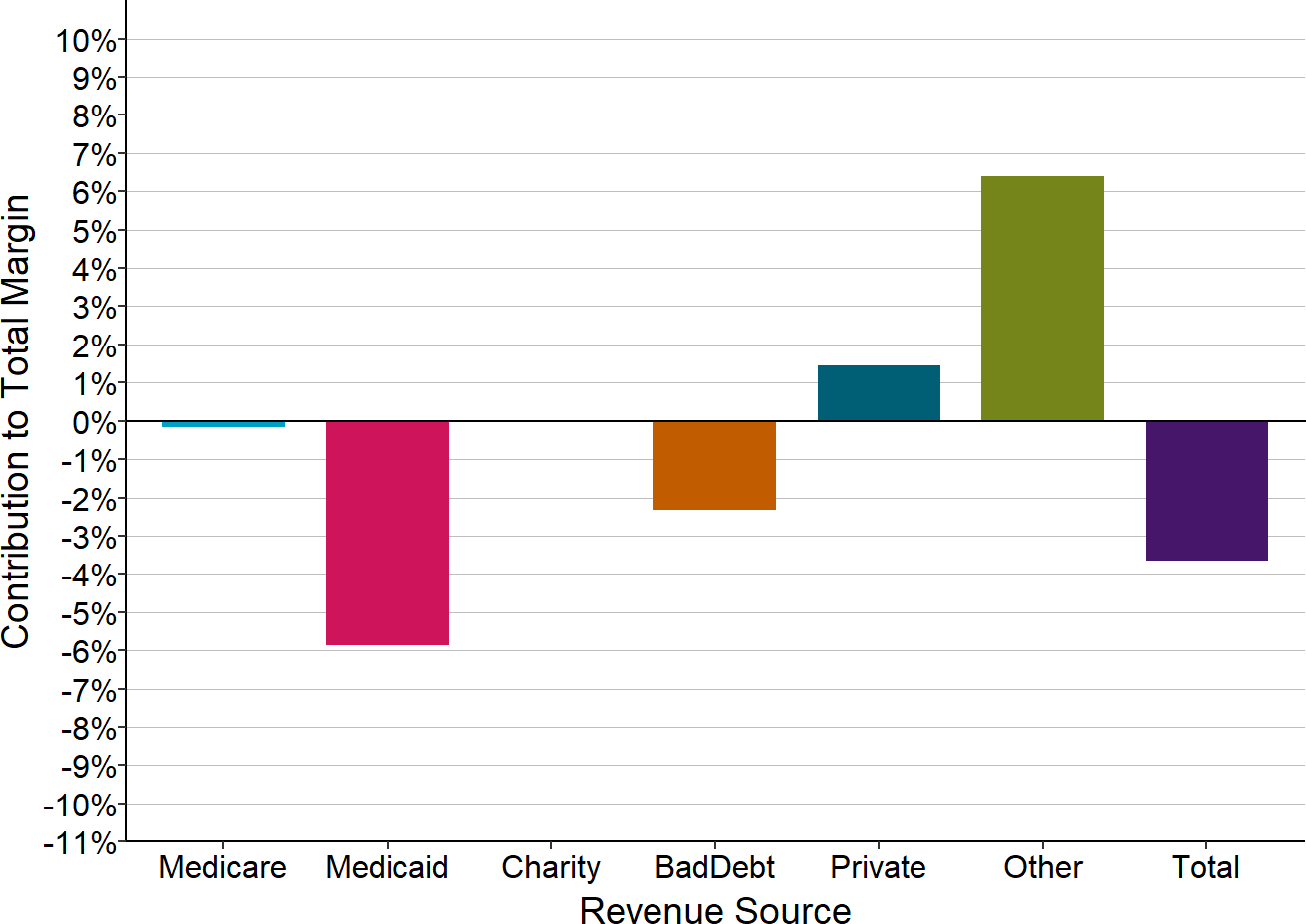

The four small rural hospitals that participated in the program had been losing money when they agreed to join, but the primary causes of the losses differed from those experienced by small rural hospitals in other parts of the country. The losses for the four small rural hospitals in the Pennsylvania Rural Health Model were primarily coming from low Medicaid payments and patient bad debt (which likely represents either uninsured or underinsured patients). Unlike most small rural hospitals across the country (and unlike other small rural hospitals in Pennsylvania), the majority of the small rural hospitals that were participating in the Pennsylvania program had not been losing money on their private pay patients. Since the Pennsylvania program is not designed to increase Medicaid payments and since private payers appear to already have been paying more than the cost of services at most hospitals, it not clear how the global budget payments in the program would help the hospitals reduce their financial losses. The most recent data available indicate that the majority of the hospitals were still losing money despite participating in the program.

Figure 6

Components of Total Margin at Small Rural Hospitals

Participating in the Pennsylvania Rural Health Model

Median for most recent year available (2023 or 2024). Margin for payer is divided by hospital’s total expenses. Includes only rural hospitals with less than $45 million total expenses that were participating in the PA Rural Health Model in 2024.

The CMS CHART Model

In August 2020, the CMS Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) announced the “Community Health Access and Rural Transformation (CHART) Model.”22 The “Community Transformation Track” of the CHART Model included a component in which rural hospitals could be paid by Medicare, Medicaid, and potentially other payers through a global hospital budget approach.23 A Notice of Funding Opportunity (NOFO) for the Community Transformation Track was issued on September 15, 2020.24 In September of 2021, CMMI selected 4 states - Alabama, South Dakota, Texas, and Washington - as sites to implement the Community Transformation Track.

In February 2023, CMMI announced that it was terminating the Community Transformation Track (and thereby the entire CHART Model) because rural hospitals were unwilling to participate. 25

The CHART Community Transformation Track had some similarities to the Pennsylvania Rural Health Model, but it also differed in significant ways.

How Rural Hospitals Would Have Been Paid in the CHART Model

Eligibility Criteria for Rural Hospitals

Rural hospitals were only eligible to participate in the Community Transformation Track of the CHART Model if they provided services to residents in one of 15 rural “Communities” across the country. The Communities were selected by CMMI based on applications submitted by state Medicaid agencies and other eligible “Lead Organizations.”26

A Community had to consist of one or more counties or census tracts, all of which are classified as rural by the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy. A Community needed to be relatively large, since its counties and census tracts would collectively need to have at least 10,000 Original Medicare beneficiaries living within them.27 Most Communities would likely have needed to have total populations of more than 60,000 total residents in order to qualify.28 Medicare beneficiaries who are enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans did not count toward the 10,000-beneficiary minimum, so Communities had to be larger in rural areas that had a high penetration of Medicare Advantage plans.

A rural hospital was eligible to participate in the CHART Model if either:

- it was located in one of the selected Communities and received at least 20% of its Medicare revenue from eligible hospital services provided to residents of that Community; or

- regardless of where the hospital is physically located, it delivered services representing at least 20% of the amount Medicare spends on eligible hospital services for all Medicare beneficiaries living in the Community.

In other words, either the residents of the Community had to represent a large share of the hospital’s services, or the hospital had to deliver a large share of the hospital services the residents of the Community received.

In addition, in order to participate in the CHART Model, the hospital had to agree to implement activities described in a Transformation Plan developed by the Lead Organization and to report quality and other information to CMMI.

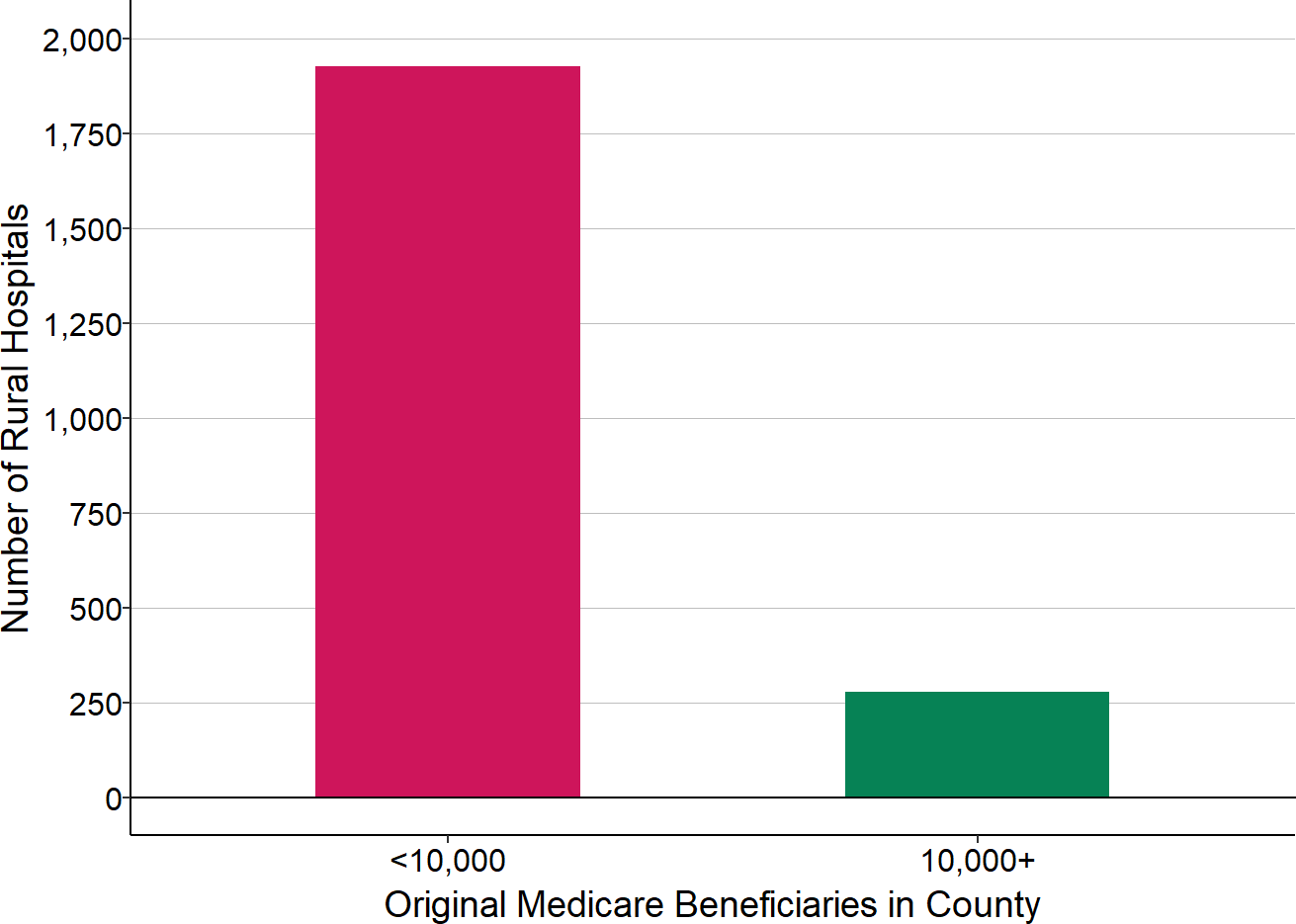

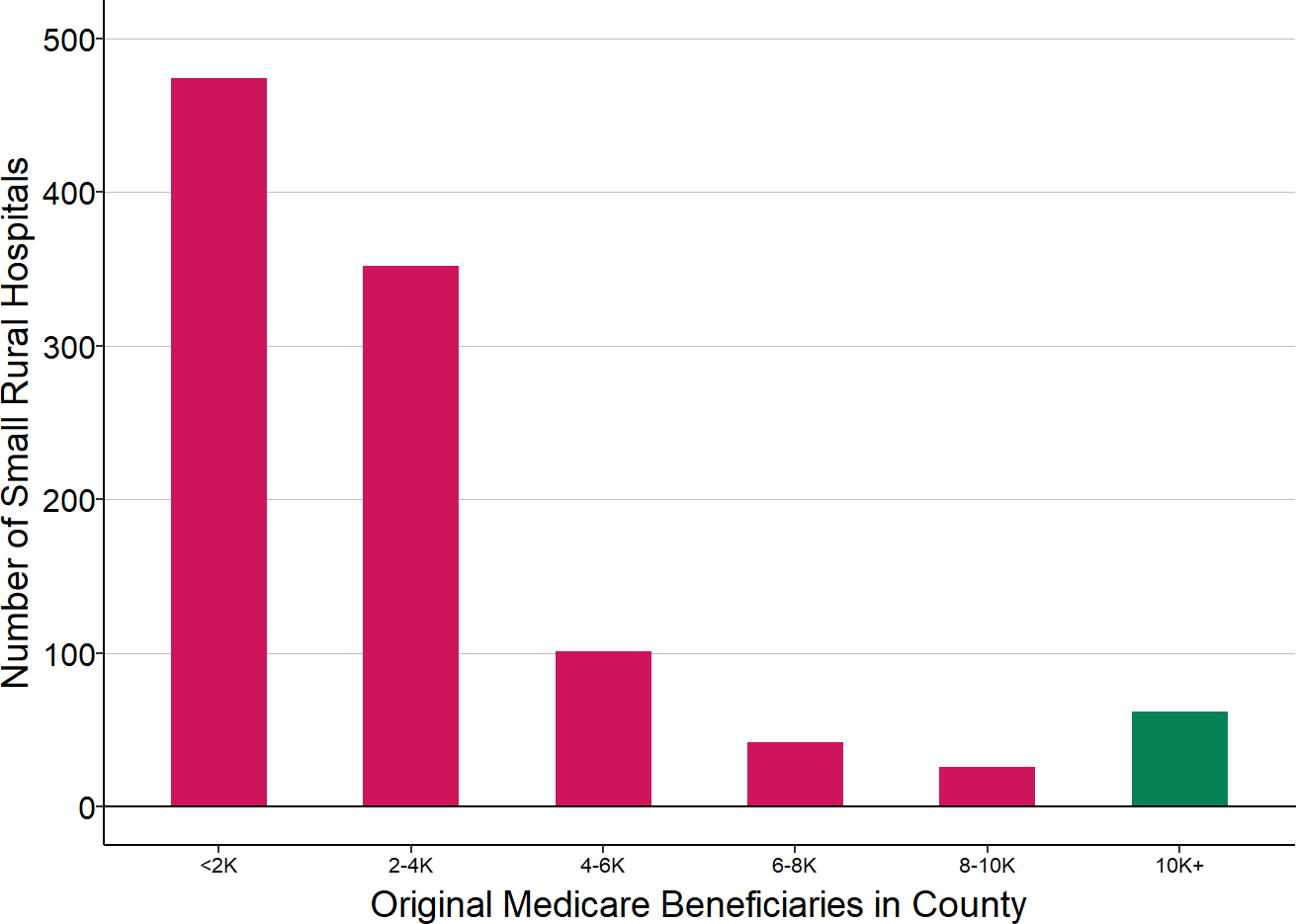

The eligibility criteria precluded most rural hospitals from participating individually. Only 16% of rural hospitals are located in a county that has 10,000 or more residents on Original Medicare, and less than 10% of small rural hospitals are located in such a county. This means that in most cases, multiple counties would have to be included and two or more hospitals would have to agree to participate in order for a Community to qualify.

Figure 7

Number of Rural Hospitals Located in Counties With More or Less Than 10,000 Medicare Beneficiaries

Source: CMS Geographic Variation Public Use File and Provider of Services File

Over 70% of small rural hospitals (those with less than $30 million in total expenses) are located in counties with fewer than 4,000 Medicare beneficiaries, and more than 40% are in counties with fewer than 2,000 beneficiaries, so this means that 3, 4, 5, or even more small hospitals would have all needed to be part of the same Community in order for any of the small rural hospitals to be eligible.

Figure 8

Number of Medicare Beneficiaries in Counties Where Small Rural Hospitals Are Located

Source: CMS Geographic Variation Public Use File and Provider of Services File. Small rural hospitals are those with less than $45 million in total expenses in the most recent year for which financial data are available. K = 000s

Method of Payment for Inpatient and Outpatient Services

If the hospital met the eligibility criteria and wished to participate in the CHART Model, the hospital would have received a single, predetermined Capitated Payment Amount (CPA) each month. This would have served as the hospital’s full payment for the eligible inpatient and outpatient services it delivered to Medicare beneficiaries. The hospital would no longer receive standard Medicare payments for these services, i.e., Critical Access Hospitals would no longer receive cost-based payments, and other hospitals would no longer receive DRG-based payments for inpatient admissions or payments under the Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS) for outpatient hospital services.

The Capitated Payment Amount would have applied only to (1) inpatient hospital services, (2) outpatient hospital services, and (3) inpatient rehabilitation services that are delivered in swing beds at Critical Access Hospitals. There would have been no change in the way a rural hospital was paid for physician services and other professional services, Rural Health Clinic services, swing bed services at non-Critical Access Hospitals, home health services, hospice services, ambulance services, or inpatient rehabilitation services outside of swing beds. It was not clear whether the CPA would only apply to hospital services delivered to beneficiaries who resided in the community, or whether it would have also replaced standard Medicare payments for services delivered to beneficiaries who do not live in the Community.29

The CPA amount would have been the same each month regardless of how many or what types of inpatient or outpatient services the hospital provided to residents of the Community during the month. For example, if the hospital admitted fewer Medicare beneficiaries for inpatient care in a particular month, it would have still received the same CPA amount as it received in the previous month, and if it delivered more outpatient testing to Medicare beneficiaries, it would not have received any additional payments from Medicare. However, as described below, the amount of payment in future years would have changed based on how what proportion of the total hospital services in the Community the hospital delivered.

Determination of the Capitated Payment Amount

Obviously, the impact of the CHART Model on a rural hospital’s finances would have depended heavily on how large the Capitated Payment Amount was compared to the payments the hospital would have otherwise received. In the Notice of Funding Opportunity, CMS described the methodology it would use to determine the Capitated Payment Amount, although it stated that the description was “for informational purposes and may change at CMMI’s sole discretion” and that “the final CPA financial methodology will be detailed further in a time and manner to be specified by CMMI.”30

Payment Amount in the First Year

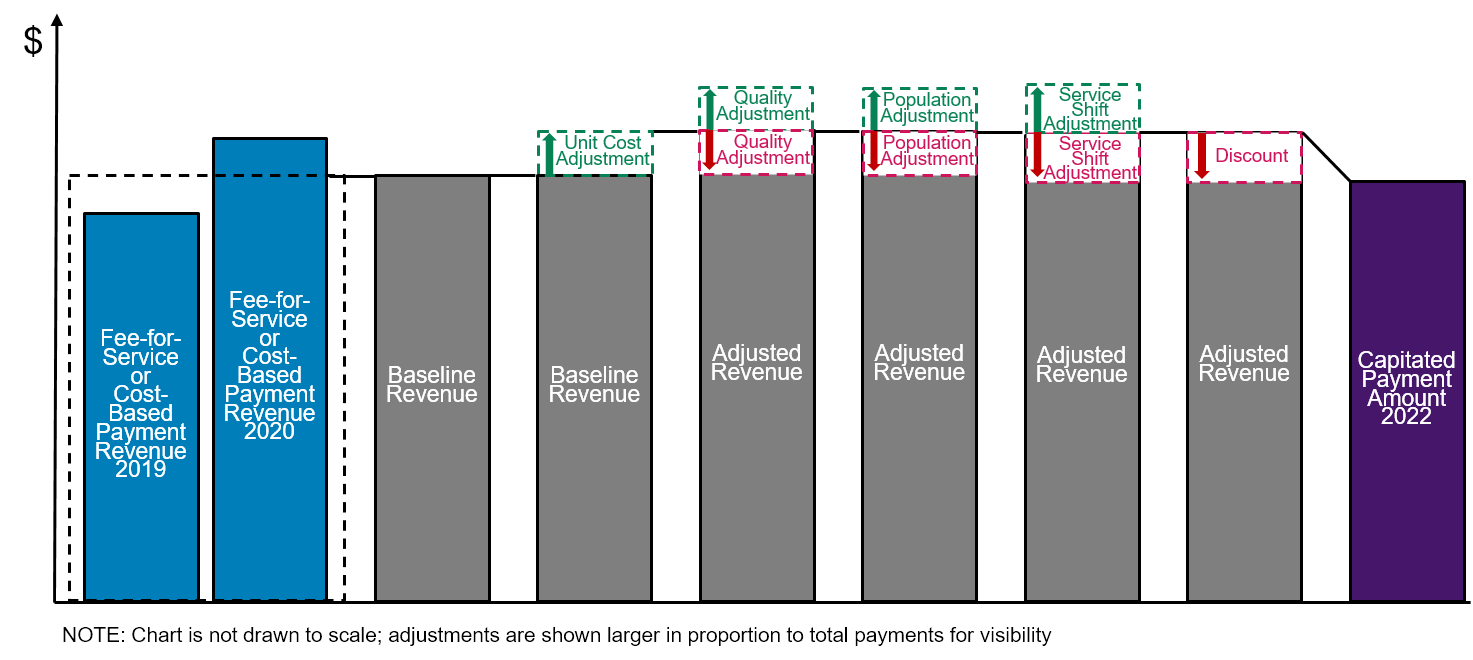

The Capitated Payment Amount (CPA) in the first year of the CHART Model was to have been determined through a complex series of steps:

- The hospital’s “baseline revenue” is calculated. The amounts Medicare paid the hospital for eligible inpatient and outpatient services two years and three years prior to the start of the model would be determined and averaged. (Because of the impacts of the pandemic, CMS announced that initally, the baseline revenue would be the average of the Medicare payments to the hospital during 2018 and 2019. )31

- A “unit price adjustment” is made. The baseline revenue reflected the amounts paid for services 2-3 years in the past, but the costs of delivering individual services and the amounts Medicare pays for services would have changed between that period and the year in which the Capitated Payment Amount is paid. The unit price adjustment was presumably intended to address this. The adjustment was to be calculated differently for Critical Access Hospitals and other hospitals:

- Critical Access Hospitals. According to the CMS methodology, “the unit price adjustment consists of the change in the interim payment rate between the cost report that the Critical Access Hospital (CAH) submitted for the baseline years and the most recently available, adjudicated cost report.”32 It is not clear exactly what “payment rate” was being referred to, since a CAH is paid for inpatient services using a per diem rate and it is paid for outpatient services based on a cost-to-charge ratio applied to the charges for services. The most recently available cost report available when the rate is initially set would likely be the later of the two baseline years (e.g., since the payments for 2023 would need to be determined in 2022, the most recent adjudicated cost report would be for 2021). There was a provision for adjusting the Capitated Payment Amount mid-year if a more recent cost report has been filed and adjudicated.

- Other hospitals. For hospitals paid through the Inpatient Prospective Payment System and Outpatient Prospective Payment System, there were two components to the unit price adjustment. (The Notice of Funding Opportunity did not describe exactly how these two components would be combined or used to adjust the baseline revenue.)

- Geographic Adjustment Factor. The changes in the wage index and capital geographic adjustment factor applicable to the hospital would be used to adjust the inpatient and outpatient portions of the baseline revenue.33

- Trend. In addition, an adjustment would be made based on the “expected” percentage change in national Medicare FFS expenditures from the baseline period to the year in which the payment will be made. This would not really be a “unit price” adjustment, since the change in total expenditures is a function of not only changes in the prices of services but in the volume and mix of services delivered to Medicare beneficiaries. Because the Capitated Payment Amount was to be set prior to the beginning of the year, the actual national Medicare spending amount for the year would not be known, so it would have to be estimated by CMS. According to the methodology description, “If the observed regional trend differs from the projected national trend by more than three percentage points, CMS may retrospectively update the trend at the time that end-of-year adjustments are made,” which presumably means that the CPA could be increased or decreased after the year ends depending on how accurate the estimate of spending was.34 It is not clear what exactly was meant by “the regional trend” or what adjustment would be made if there was a difference of more than three percentage points.

- Adjustments are made for quality. The payment would have been adjusted for any changes in the penalties applicable to the hospital under the CMS Value-Based Purchasing Program, the Hospital Acquired Condition Reduction Program, and the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program between the baseline years and the current year. Since these programs only apply to inpatient services, not outpatient services, presumably the adjustment would have only appled to the subset of the baseline revenues derived from inpatient services.

- Adjustments are made for changes in the population served. This would have included three separate components:

- Population size adjustment. The population served was to be defined as the number of Original Medicare beneficiaries who “reside” in the Community for the majority of the 12 month period35 that began 18 months prior to the year in question (i.e., either the baseline years or the current year) times the number of months they are there.36 The number of beneficiaries in the community in the baseline years would have been compared to the number in the current year, and the CPA would be adjusted based on the change in the number of beneficiaries. The methodology did not specify exactly what the adjustment would be, but presumably if the number of beneficiaries had increased or decreased by a certain percentage, the CPA would be increased or decreased by the same percentage. (The document stated that “the population adjustment will avoid over-payment for Eligible Hospital Services by reducing revenue from a Participant Hospital’s baseline CPA if the population served by the Participant Hospital decreased between the baseline years and the Performance Period.”37)

- Demographic adjustment. The demographic-only HCC scores of the population in the two time periods were to be compared to determine whether the population had increased in age or the gender mix had changed.38 The methodology did not specify whether the CPA would be adjusted in direct proportion to the change in the average HCC score.

- Shift in eligible hospital services. The third adjustment was to be based on whether there had been a “change in the distribution of services between hospitals.” The method of calculating this was not specified, but the document stated the adjustment was intended to “avoid over-payment for Eligible Hospital Services by reducing revenue from a Participant Hospital’s baseline CPA if … Eligible Hospital Services shifted between health care providers between the baseline years and the Performance Period,” so presumably this meant that if the residents of the community received a higher proportion of their hospital services at other hospitals, the CPA for the rural hospital would be reduced.39

- A “discount” is applied. After all of the other adjustments had been made, the resulting amount would be reduced by a percentage that CMS referred to as the “discount.” The discount in the first year was 0.5% (i.e., one-half of one percent). The document stated that the discount was included “in order for payers to realize savings.”40

- Mid-year adjustments are made. The Capitated Payment Amount was to be adjusted mid-year if additional data became available about changes in the population served or if a newly adjudicated cost report for a Critical Access Hospital became available.

- Additional adjustments are made after the end of the year. Although the Capitated Payment Amount was supposed to be a “prospective payment,” it was to be retroactively adjusted six months after the end of the year based on claims data. In addition to the population adjustments described above, the NOFO said there “may” be an option for the hospital to receive an “outlier adjustment” to address “unexpected, catastrophically expensive utilization.” If CMS concluded that the Capitated Payment Amounts paid to the hospital had been too high, CMS would reduce the CPA to the hospital in the next year or potentially require a lump-sum repayment of the difference.41

The final Capitated Amount could be higher or lower than revenues in previous years depending on the relative magnitudes of the various adjustments.

Figure 9

Methodology for Determining the Initial Capitated Payment Amount in the CMS CHART Model

Payment Amount in Subsequent Years

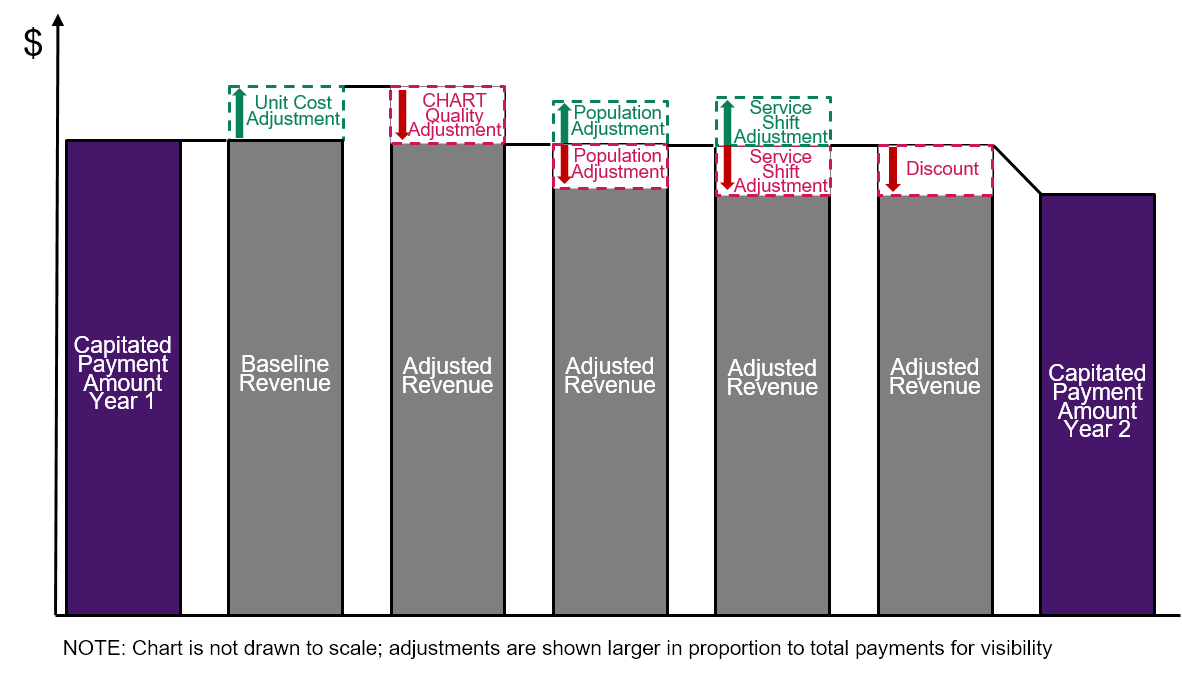

In subsequent years, the methodology for determining the Capitated Payment Amount was to be similar to what is described above, but with three changes:

- The adjustments for changes in unit prices, population size, demographics, and service use would be applied to the Capitated Payment Amount from the previous year. The initial CPA was based on the average of the amount of fee-for-service or cost-based payments the hospital received in prior years. However, in the second and subsequent years, the current CPA would serve as the starting point for determining the next year’s CPA using all of the various adjustments described above.

- Additional reductions in payments would be made based on quality measures. In addition to the adjustments based on current CMS hospital quality programs described above, the CPA was to be reduced by up to 2% based on quality measures specifically defined for the CHART program.42 The quality adjustment would be based on a hospital’s performance on six measures, three of which would be required for all hospitals (per capita hospital admissions for chronic conditions, the all-cause readmission rate, and HCAHPS patient experience ratings), and an additional three that would be selected by the Lead Organization from a menu of seven measures (use of pharmacotherapy for opioid use disorder, use of high dosage opioids for non-cancer patients, the rate of Cesarean sections, the rate of post-partum contraceptive care, the rate of flu vaccination, screening and follow-up plan for depression, and continuity of primary care for children with medical complexity). It is not clear what would have been considered good or bad performance by a small rural hospital on these measures; most of the measures on the second list would have relatively small denominators and would be difficult or impossible to measure reliably in small rural communities.43

- Payments would be reduced by larger amounts each year through higher discounts.

- A 1% discount in Year 2. In the second year of the program, the CPA was to be reduced by 1.0% rather than 0.5%.44

- Discounts as high as 2.5% in Year 3. In the third year, the amount of the discount was to range from 1.0% to as much as 2.5% depending on the total amount Medicare was paying through Capitated Payments for services in the Community. If the total of the CPA payments to all participating hospitals in the Community was less than or equal to $15 million, all of the payments were to be reduced by 2.5%. If the total CPA payments were higher than $15 million, smaller discounts were to be used, with a minimum discount of 1% for communities where $120 million or more of CPA payments were being made. The document stated that the higher discounts were intended to provide “an incentive for Communities to recruit more hospitals to participate” and to increase “the likelihood that the [program] will yield savings that meet or exceed” the amount of the grant funding that is being provided to the Community as part of the CHART model.45

- Maximum discounts between 3% and 4% in Years 4 through 6. In subsequent years, the maximum discount was to increase to as much as 4%, and the threshold for receiving only a 1% discount was to increase to $300 million in total CPA payments.

Figure 10

Methodology for Determining the Second Year Capitated Payment Amount in the CMS CHART Model

Payments from Other Payers

The state Medicaid agency was required to participate and serve as an “Aligned Payer” in order for a Community to be selected. However, Medicaid payments did not need to change until the second year of the program. Moreover, only 50% of the participating hospitals’ Medicaid revenue needed to be paid through a Capitated Payment Arrangement in the second year; that percentage was to increase to 60% in the third year and 75% in the fourth and subsequent years. The document did not say whether these percentages would apply to all Medicaid revenues or only the revenue for services delivered to residents of the Community.46

Participation by commercial payers as Aligned Payers was “recommended but not required,” and there was no requirement for Medicare Advantage plans to participate, so it is possible that payments would have only changed for Original Medicare beneficiaries and a portion of Medicaid beneficiaries.47

The payment methodology used by Medicaid and other Aligned Payers was supposed to be “similar” to the Medicare methodology, but it did not need to be identical. The NOFO stated that an “Aligned Payer may implement their capitated payment arrangement with Participant Hospitals differently based on their plan benefits and member populations.”48 The NOFO specifically stated that other payers did not need to make adjustments for Critical Access Hospitals based on changes in the hospitals’ costs.49

The Impact of the CHART Model on Rural Hospitals

The complexity of the payment methodology made it difficult for a rural hospital to understand what impact participation in the CHART Model would have. However, careful examination shows that:

- Rural hospitals would have been paid less for services under the CHART Model than under current payment systems.

- Payments to rural hospitals under the CHART Model would still have been based on the volume of services delivered.

- Hospital costs and losses would have increased under the CHART Model. Hospitals would have still lost money if they reduced avoidable services such as unplanned hospital readmissions or Emergency Department visits.

Rural Hospitals Would Have Been Paid Less for Services Under the CHART Model

Most rural hospitals are losing money on the services they deliver to patients because the payments they receive from Medicare, Medicaid, and private health insurance plans are less than what it costs for the hospitals to deliver the services. The CHART Model would not only have failed to solve this problem, it would have made it worse, because it was explicitly intended to reduce the amount that payers spend.

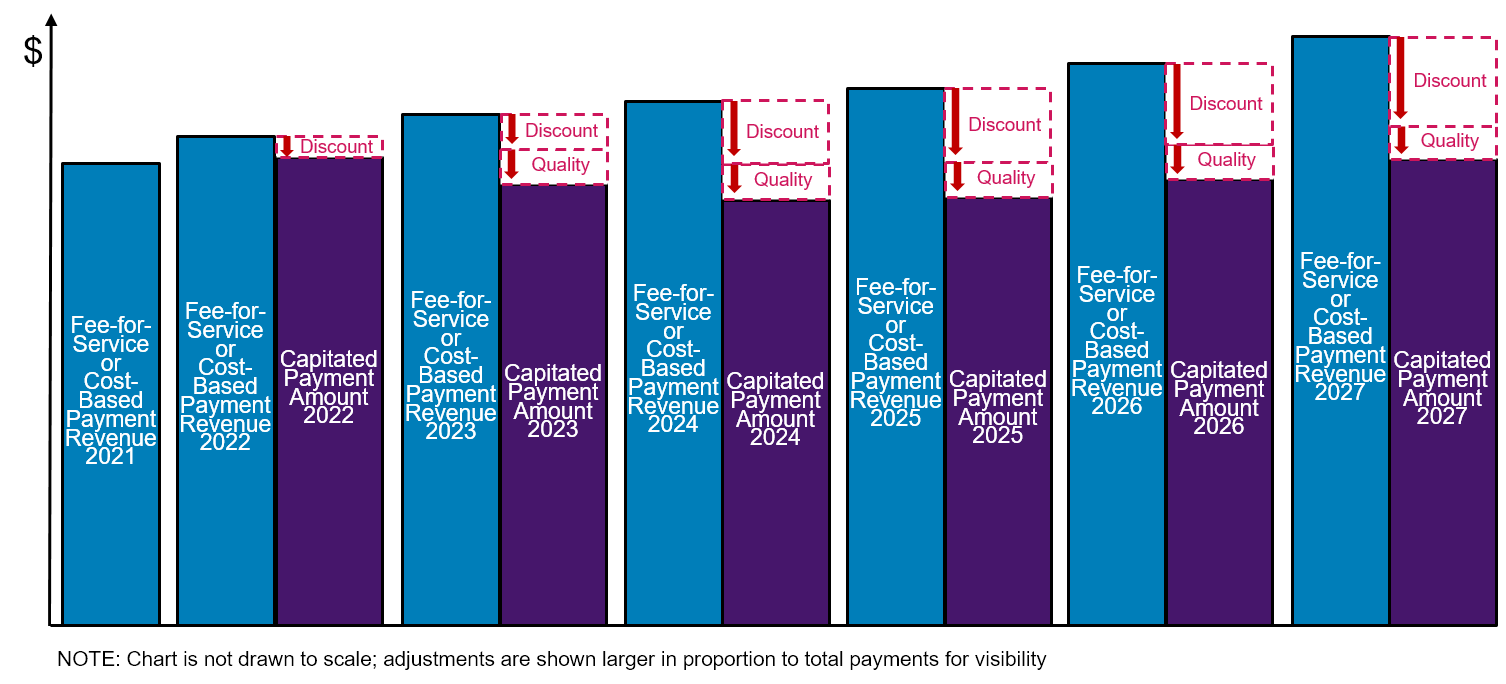

Capitated Payments Would Have Been Reduced Below Current Inadequate Levels. The “discount” in the methodology reduced the Capitated Payment Amount below what the hospital would have received under current payment systems. At most rural hospitals, payments from Medicare and other payers are below the cost of services, so if the Capitated Payment was even lower, the hospitals’ losses would have increased.50

Payment Reductions Would Increase Over Time. The discount in the first year was 0.5%, and it would have doubled to 1% in the second year. It would have doubled again to 2.0% or more in the third year for most hospitals,51 and it would have continued to increase by smaller amounts in each subsequent year to as much as 4.0% in the sixth year. In addition, beginning in the second year, a new quality adjustment would have been added that could have reduced payments by as much as 2% below the discounted amount. As a result, the hospital could receive less revenue during the demonstration than it received prior to entering.

Figure 11

Increasing Reductions in Capitated Payment Amounts Over Time

in the CMS CHART Model

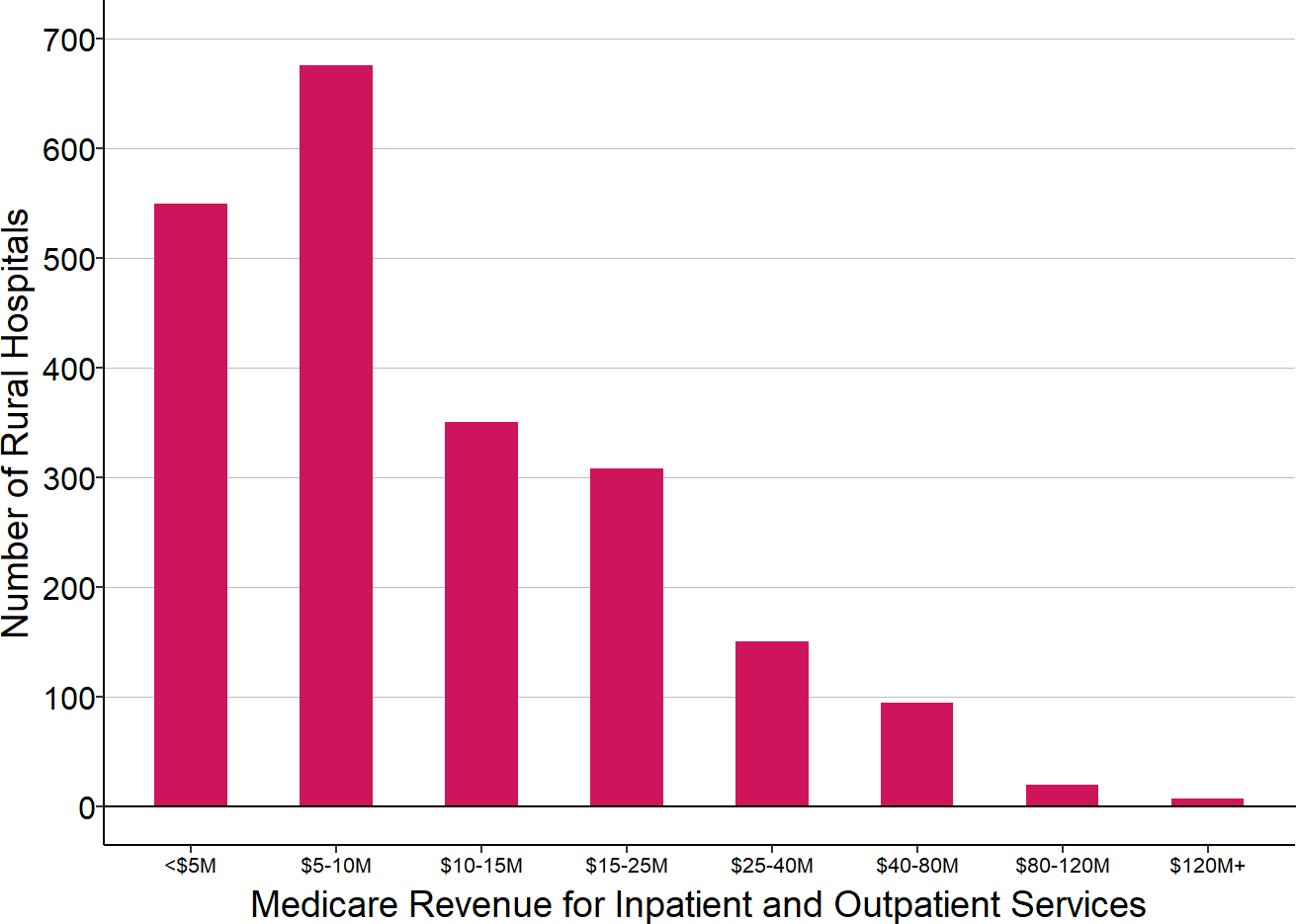

- Payment Reductions Would Have Been Larger for Smaller Rural Hospitals and Smaller Rural Communities. The size of the discount would have been based on the total amount of Medicare revenue included under the Capitated Payment Arrangement in a Community. The percentage reduction in payment to the hospital would be larger if the total amount of Medicare revenue involved was smaller. In the sixth year of the program, the Capitated Payment Amount was to be reduced by 4% if the hospitals in the Community received less than $15 million in Medicare payments for the services covered by the Capitated Payment Amounts, and the discounts would only have been 2% or less if there were more than $160 million in total Capitated Payments in the Community. As noted earlier, CMS stated that the higher discounts were intended to provide “an incentive for Communities to recruit more hospitals to participate” and to increase “the likelihood that the [program] will yield savings that meet or exceed the amount of the cooperative funding.” However, 72% of rural hospitals receive less than $15 million per year in Medicare payments for inpatient and outpatient services, and the majority of rural hospitals have less than $10 million in Medicare revenue, so a large number of hospitals would have had to participate in a Community in order to qualify for smaller discounts.

Figure 12

Total Medicare Inpatient and Outpatient Revenue

at Rural Hospitals

Amount in most recent year at U.S. rural hospitals.

- Payments for Critical Access Hospitals Would Have No Longer Increased When Costs Increased During the Year. Most small rural hospitals are classified as Critical Access Hospitals; currently, if their costs increase unexpectedly during the year, their cost-based payments from Medicare increase proportionately. For example, if one of the hospital’s emergency physicians or nurses resigns or becomes ill and the hospital has to pay more for a temporary employee to fill the gap, the increase in the hospital’s personnel cost that year will result in a higher Medicare payment for that year. Under CHART, however, the Capitated Payment Amount for the year would not have increased if the hospital’s costs increased unexpectedly during the year, resulting in lower revenues and higher losses under CHART than under the current payment system.

Hospital Payments Would Still Have Been Based on the Volume of Services

CMS said that the CHART Model payments would have provided “a predictable and stable revenue stream” and that hospitals’ revenues would no longer be “predicated on realized volumes.” However, most of the hospital’s revenue would still have come from fee-for-service payments, and even the Capitated Payments would still have been tied to the number of services delivered.

- Payments Would Not Have Changed at All for Most of the Hospital’s Services.

- Medicare: Although Medicare is a large payer at most rural hospitals, it does not represent the majority of revenues at most hospitals. Moreover, the Capitated Payment Amount would have applied only to inpatient hospital services and outpatient hospital services. Medicare would have continued to pay for physician services and other professional services, Rural Health Clinic services, swing bed services at non-Critical Access Hospitals, home health services, hospice services, ambulance services, and inpatient rehabilitation services outside of swing beds using fee-for-service payments. Medicare payments for inpatient and outpatient services only represent about one-third of total revenues at small rural hospitals and less than one-fourth of revenues at larger rural hospitals.

- Medicaid: Although the state Medicaid program was required to participate in the CHART Model in order for a Community to be selected, Medicaid payments were not required to change until the second year, and even then, only 50% of Medicaid payments had to be provided through a capitated payment arrangement. Medicaid revenues only represent about 9-10% of total revenues at small rural hospitals, so if only 50% of Medicaid payments changed, that would affect less than 5% of the hospital’s revenue.

- Private Insurance: There was no requirement that private health plans participate in the program, so under the CHART Model, a hospital would likely have continued to receive fee-for-service payments for most patients with private insurance.

- Total: In combination, it is likely that less than half of a hospital’s revenues would have been provided through Capitated Payments. For Critical Access Hospitals, that would primarily represent a change from cost-based payment, not a shift from fee-for-service payments.

- The CHART Model’s Capitated Payment Would Have Been Reduced if the Population of the Community Decreases. Many rural hospitals have had financial difficulties because population losses in the rural communities they serve have caused a reduction in the number of services they deliver and the associated fee-for-service revenues. The CHART Model would not have prevented these losses of revenue; if the number of Medicare beneficiaries living in the Community decreased, the “population adjustment” in the payment methodology would have reduced the hospital’s Capitated Payment Amount, which would have had the same negative impact on the hospital’s revenues as the loss of fee-for-service revenues. In some cases, the hospital could have been even worse off under the CHART Model, because the Capitated Payment would be reduced when the population decreased even if the number of services delivered did not decrease.

Figure 13

Sources of Revenue at Rural Hospitals

Median amounts in three most recent years (excluding 2020) at U.S. rural hospitals. Private/Other includes Medicare revenues for services other than inpatient and outpatient hospital services.

- The CHART Model’s Capitated Payment Would Have Been Reduced if the Hospital Discontinued a Service Line. Under the CHART Model, if a hospital stopped delivering a particular type of service, the Capitated Payment Amount would have been reduced in the following year. As stated in the Notice of Funding Opportunity, “When Participant Hospitals shut down a service line, they will lose revenue from that service line…”52 The same would have been true if the hospital delivered fewer services and patients obtained those services at another hospital instead; the Notice of Funding Opportunity stated that the Capitated Payment Amount would be reduced “if Eligible Hospital Services shifted between health care providers.” As a result, the hospital would have less revenue to cover the fixed costs of essential services. The only cases in which the hospital could continue to receive the same revenues when it delivered fewer services would be when it reduced avoidable utilization in an existing service line and patients did not go to other hospitals to receive those services.53

Rural Hospital Costs and Losses Would Have Increased Under the CHART Model

The CHART Model presumed that the “financial flexibility” of the Capitated Payment and “operational flexibilities” through regulatory waivers would allow a hospital to “achieve savings … through reductions in potentially avoidable utilization” and would “incent community-based, preventive care.” However, CMS provided no information to support this assertion. In fact, it is unlikely that hospital costs would decrease and more likely that they would increase under CHART. As a result, it is likely that rural hospitals participating in CHART would have experienced greater financial losses than they would otherwise.

- Reductions in Avoidable Utilization Would Cause Financial Losses. In the NOFO, CMS said “it is expected that Participant Hospitals can achieve savings, despite the presence of a discount, through reductions in potentially avoidable utilization.”54 However, at the smallest rural hospitals, staffing is typically at or near the bare minimum needed to deliver essential services, and even if some of those services could be avoided, the hospital could not eliminate any staff or equipment as a result. For example, a small rural hospital with one physician on duty in the ED will still need that physician on duty even if there are fewer visits to the ED. If a hospital reduces the frequency with which patients are readmitted to the hospital, it will not be able to reduce nursing staff on the inpatient unit.55 Although the Capitated Payment would not decrease if there was a reduction in avoidable utilization, the hospital would only be receiving the Capitated Payment for a subset of patients, so fee-for-service revenues would decrease for the remaining patients, causing losses.