STATUS QUO |

SCENARIO A Fewer ED Visits, No Change in Non-Local Spending |

SCENARIO B Fewer ED Visits, Decrease in Non-Local Spending |

SCENARIO C Fewer ED Visits, Increase in Non-Local Spending |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount | Amount | Change | Amount | Change | Amount | Change | |

| Medicare Spending | |||||||

| Local Spending | $22,676,498 | $22,651,959 | −0.1% | $22,651,959 | −0.1% | $22,651,959 | −0.1% |

| Non-Local Spending | $68,029,495 | $68,029,495 | 0.0% | $65,988,610 | −3.0% | $70,070,380 | 3.0% |

| Total Spending | $90,705,993 | $90,681,454 | −0.0% | $88,640,569 | −2.3% | $92,722,339 | 2.2% |

| Savings | $24,540 | $2,065,424 | ($2,016,345) | ||||

| Pct Savings | 0.0% | 2.3% | −2.2% | ||||

| ED Visits | |||||||

| ED Visits | 12,500 | 11,250 | −10.0% | 11,250 | −10.0% | 11,250 | −10.0% |

| Revenue | |||||||

| Medicare Facility Cost | $1,154,000 | $1,241,000 | 7.5% | $1,241,000 | 7.5% | $1,241,000 | 7.5% |

| Medicare Physician Fee | $1,113,000 | $1,002,000 | −10.0% | $1,002,000 | −10.0% | $1,002,000 | −10.0% |

| Medicare Shared Savings | $0 | $1,033,000 | ($1,008,000) | ||||

| Subtotal Medicare | $2,268,000 | $2,243,000 | −1.1% | $3,276,000 | 44.4% | $1,235,000 | −45.5% |

| Other Payers Facility Fee | $675,000 | $608,000 | −9.9% | $608,000 | −9.9% | $608,000 | −9.9% |

| Other Payers Physician Fee | $338,000 | $304,000 | −10.1% | $304,000 | −10.1% | $304,000 | −10.1% |

| Subtotal Other Payers | $1,012,000 | $911,000 | −10.0% | $911,000 | −10.0% | $911,000 | −10.0% |

| Uninsured Facility Fee | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | |||

| Uninsured Physician Fee | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | |||

| Subtotal Uninsured | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | |||

| Total Revenue | $3,280,000 | $3,154,000 | −3.8% | $4,187,000 | 27.7% | $2,146,000 | −34.6% |

| Cost | |||||||

| Baseline Cost | $3,213,000 | $3,213,000 | 0.0% | $3,213,000 | 0.0% | $3,213,000 | 0.0% |

| Care Management | $0 | $87,000 | $87,000 | $87,000 | |||

| Total Cost | $3,213,000 | $3,300,000 | 2.7% | $3,300,000 | 2.7% | $3,300,000 | 2.7% |

| Margin | |||||||

| Margin | $68,000 | ($146,000) | −314.7% | $887,000 | 1,204.4% | ($1,154,000) | −1,797.1% |

| Pct Margin | 2.1% | −4.4% | 26.9% | −35.0% | |||

ACOs, Shared Savings, and Global Payments

Most small rural hospitals are unlikely to benefit from forming an Accountable Care Organization (ACO) or participating in shared savings programs. Under the Medicare Shared Savings Program, the only way a hospital can receive more money is by reducing Medicare spending by a sufficient amount, and over one-third of the ACOs in the program have been unable to do that. It is particularly difficult for small rural ACOs to receive shared savings bonuses because they have to achieve a bigger percentage reduction in spending to qualify for a bonus than larger ACOs, and the rates of service utilization are generally lower in small rural communities so there are fewer opportunities to generate savings.

Many small rural hospitals could be harmed financially by participation in shared savings programs. If a hospital hires additional staff or consultants to help it succeed in the shared savings program, it will increase its costs with no guarantee of receiving any additional payments to offset the higher expenses. If the hospital reduces the number of services it delivers to patients, it will create savings for payers but it will also reduce its own revenues by more than any shared savings bonus it would receive.

Small rural hospitals could be particularly harmed if they accept “downside risk.” In the future, ACOs will be required to pay penalties if total healthcare spending for their patients increases. Small rural hospitals do not deliver and cannot control many of the most expensive services their residents may need, and a requirement that the rural hospital pay penalties when rural residents need expensive services at urban hospitals would worsen the rural hospitals’ financial problems. There are also serious problems with the methodologies used for risk adjustment and setting of spending targets that could particularly harm small ACOs in rural areas.

Residents of rural communities could be harmed by the incentives in shared savings and downside risk programs. The primary goal of these incentive programs is to reduce spending for payers, not to improve the quality of care for patients. Bonuses and penalties based on changes in payer spending create a financial incentive for ACO participants to withhold services that patients need, to discourage patients from receiving high-cost services, and to avoid providing care to patients who have serious health problems. The limited number of quality measures in shared savings programs cannot prevent this from occurring.

The Promise and Problems of ACOs

Many small rural hospitals have been told that their best and perhaps only path to sustainability is to form or join an “Accountable Care Organization” (ACO), because of the potential to receive higher payments for delivering high-quality, efficient care than they can receive under standard fee-for-service or cost-based payment systems.

The Affordable Care Act defined an ACO as a group of providers that work together to manage and coordinate care for their patients and that are willing to be accountable for the quality, cost, and overall care of those patients.1 It might seem that a small rural hospital that operates one or more Rural Health Clinics would be ideally suited to serve as an ACO, since it delivers primary care and the most commonly-used outpatient services to the residents of its community, as well as inpatient and post-acute care for common medical conditions and chronic diseases. Moreover, if participation in the ACO could result in higher payments for the rural hospital, it could improve the hospital’s financial status, helping it to continue delivering existing services to the community and potentially even to improve and expand those services.

The problem is that the “shared savings” and “two-sided risk” payment systems used by Medicare and other payers to pay ACOs can actually make a small rural hospital worse off financially than it would be under current payment systems. Although it is possible that a small rural hospital could improve its financial margin by forming or joining an ACO that is paid in these ways, it is more likely that the hospital will receive no financial benefit at all or even be penalized financially for being part of the ACO. Moreover, because current ACO programs have failed to generate significant savings for payers, the payment methodologies are being changed in ways that will make it even more difficult for rural hospitals to benefit in the future and more likely that they will be financially harmed.

How “Shared Savings” Actually Works

A shared savings program sounds simple and attractive. Physicians and hospitals are told that if they form an ACO and if they are able to deliver high-quality health care to patients while reducing the amount that the patients’ health insurance plans spend on their care, they will receive a bonus payment based on a share of the savings that the payer has received. The devil is in the details, however, particularly in the way determinations are made about which patients the ACO is accountable for, when savings have occurred, and how much of the savings should be shared.

The Medicare Shared Savings Program uses the following methodology to make those determinations:2

CMS determines what subset of the Original Medicare beneficiaries in the community are “assigned” to the ACO. This is based on whether a beneficiary has received most of their primary care services at the hospital’s clinic or from primary care practices in the community that have agreed to be part of the ACO. A beneficiary can also be assigned to the ACO if they explicitly notify CMS that the clinic or affiliated practice is responsible for coordinating their overall care. An ACO is only eligible to participate in the Medicare Shared Savings Program if it has one or more affiliated primary care clinics/practices and if there will be at least 5,000 Medicare beneficiaries assigned to those clinics/practices.

When the rural hospital or any other provider delivers a service to a Medicare beneficiary who has been assigned to the ACO, CMS pays the exact same amount for that service as it does currently. Participation in the ACO does not allow a hospital to be paid directly for any services that the hospital or clinic provide if they cannot be paid for them under standard payment systems.

At the end of each year, CMS calculates the total amount it has paid for all healthcare services to the assigned beneficiaries during the year. CMS compares that actual amount of spending to a “benchmark” amount that represents what CMS projects it would have spent during the year if the ACO had not existed. The benchmark is calculated by taking the average total per-patient spending on the ACO’s patients in previous years, risk-adjusting that amount, and then inflating that based on the amount that risk-adjusted per-beneficiary spending increased in other parts of the country during the previous year. Medicare spending on the beneficiaries assigned to the ACO does not have to actually decrease in order for the ACO to be credited with “savings.” Spending on the assigned beneficiaries merely has to increase less than what CMS projects would have happened in the absence of the ACO.

If (and only if) the actual spending on the ACO’s patients is lower than this benchmark amount by more than the “Minimum Savings Rate” (MSR) established by CMS, the ACO is potentially eligible to receive a bonus payment. The Minimum Savings Rate that must be achieved is higher for smaller ACOs because of the concern that small ACOs could appear to have savings that are simply due to random variations in spending from year to year. CMS requires that for an ACO with 5,000 beneficiaries, actual spending must be at least 3.9% below the projected benchmark in order to qualify for a bonus, whereas an ACO with 60,000 beneficiaries only needs to have spending that is 2.0% lower.

Assuming this minimum savings level is achieved, the maximum bonus that the ACO can receive is equal to a percentage of the difference between the benchmark and the actual spending. The percentage is either 40%, 50%, or 75% depending on the specific “Track” in the Medicare Shared Savings Program in which the ACO is participating.

The actual bonus (the “earned performance payment”) is determined by reducing the maximum bonus amount based on the ACO’s “quality score.” The quality score is determined by calculating the performance of the hospital, clinic, and other providers who are part of the ACO on 23 quality measures and comparing their performance to national percentiles. If the quality score is too low, there will be no bonus at all.

If the ACO does qualify for a quality-adjusted bonus, the amount is reduced by 2% to meet Congressional sequestration requirements. If the amount of savings is so large that it exceeds a maximum percentage of the benchmark expenditures established by CMS, the bonus is capped at the maximum.

In order to receive a higher percentage of any savings, a subset of ACOs have agreed to accept “two-sided risk,” which means that in addition to receiving bonuses when savings occur, they are required to pay penalties if actual spending exceeds the benchmark spending level by more than a “Minimum Loss Rate.” When this occurs, the penalty is based on a percentage of the difference between the actual and benchmark spending, up to a maximum amount. Under revisions to the program announced in 2019, all ACOs will ultimately have to accept two-sided risk.3

Other payers use variations on this same approach, but private health plans generally do not make the details of their shared savings methodologies publicly available, so it is difficult to determine whether it is easier or harder for physicians and hospitals to receive shared savings bonuses from them.

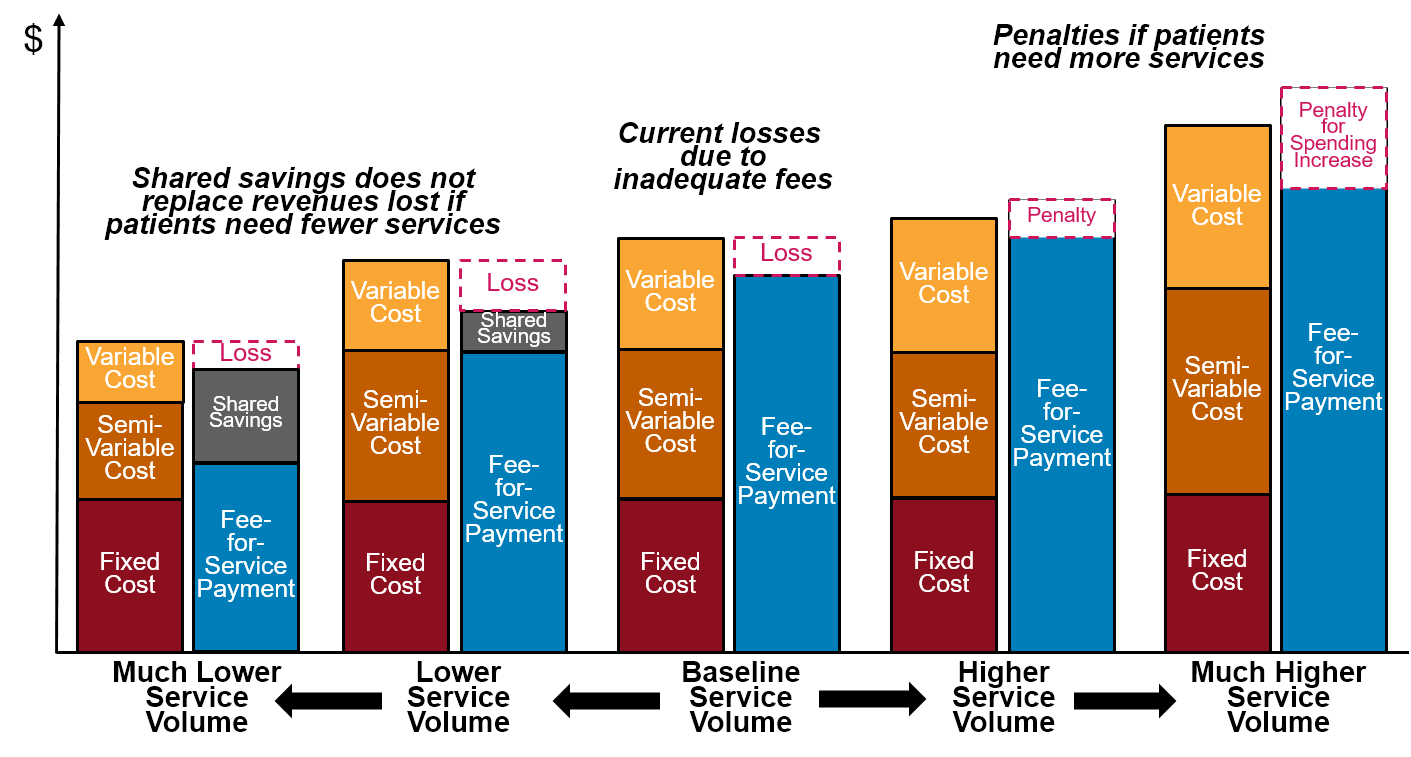

Why Shared Savings Programs Don’t Fix the Problems With Current Payment Systems

Under a Shared Savings program, a hospital receives bonuses and pays penalties based on how spending changes for payers, regardless of whether and how much costs change for the hospital and whether the hospital’s revenues are adequate to support those costs. Since the majority of costs are fixed for small hospitals, and the majority of costs are fixed in the short run for all hospitals, small changes in the number of services delivered will generally change the hospitals’ revenues more than its costs. Tying the hospital’s payments solely to whether payers spend more or less does not ensure that the revenues will match the hospital’s costs.

For example, the table below shows an Emergency Department at a hypothetical Critical Access Hospital that creates a care management program to help local residents stay healthy and avoid trips to the Emergency Department. The ED is assumed to have 12,500 visits per year and to have operating costs similar to what was shown in .

It is assumed that the rural hospital participates in a shared savings program for the Medicare beneficiaries living in the community. Under the program, the hospital will receive a bonus equal to 50% of the savings if total Medicare spending on the local residents is reduced by at least 2%4, but the hospital will have to pay a penalty of 50% if spending increases by more than 2%.5 Savings are measured based on how total Medicare spending on the local residents changes, including both spending at the rural hospital and spending at other hospitals outside the local community.

The example assumes that spending on ED visits represents 10% of total spending at the hospital and that spending at the hospital represents 25% of total Medicare spending on the local residents (i.e., 75% of Medicare spending is for services delivered by hospitals located in other communities or by local healthcare providers other than the rural hospital).

In Scenario A, the number of ED visits decreases by 10%, but there is no change in any other services received by the local residents. The hospital’s ED revenue decreases because a portion of its revenue is tied to fees for each visit (under a Shared Savings program, there is no change in the way the hospital is paid for individual services). Although the decrease in the hospital’s revenue for ED visits represents savings for Medicare, the savings falls short of the minimum amount needed to qualify for a shared savings bonus. Since the hospital has incurred additional expenses to hire the care manager, has lost revenues on ED visits, and does not qualify for any shared savings payment, the hospital incurs a loss.

In Scenario B, the number of ED visits also decreases by 10%. However, the better care management services delivered by the hospital also results in local residents receiving fewer services at other hospitals and so spending elsewhere decreases by 3%. This overall reduction in spending is large enough to qualify for a shared savings bonus. That bonus is greater than the cost of the care manager and the loss of ED revenues, so the hospital makes a significant profit.

In Scenario C, the number of ED visits decreases by 10%, but spending at other hospitals increases by 3% rather than decreases. This increase is large enough to result in a penalty for the hospital under the shared savings/risk program. Now, in addition to incurring additional costs for the care manager and losing revenue for ED visits, the hospital has to make a payment to Medicare, so the hospital incurs a significant loss.

The result is that the hospital is still penalized for reducing ED visits; its profitability depends on how much Medicare spends at other hospitals, not at the hospital itself. Since the rural hospital has no direct control over what services other hospitals deliver, it is more likely that the hospital would experience losses than profits under the shared savings program.

Figure 1

Changes in Hospital Margins Under Shared Savings/Risk

With a Care Management Program to Reduce ED Visits

The fundamental flaws in the shared savings approach became particularly apparent during the 2020 coronavirus pandemic:

Hospitalization rates increased because of the large number of patients infected with the virus, but the increases differed dramatically from community to community depending on the rate of infection and the susceptibility of the population to infection. The Shared Savings Program’s risk-adjustment methodology does not adjust for changes or differences in the rate at which patients experience acute conditions, so ACOs in communities with high infection rates could be penalized because spending on inpatient care increased by a higher amount.

Many patients who were not infected by the virus delayed or avoided receiving other healthcare services, including services that they may have needed to prevent more serious conditions and avoid the need for more expensive treatments. Under the Shared Savings Program methodology, this reduction could be treated as “savings” in 2020, but if patients have simply deferred the services until 2021, or if they end up needing even more services because they avoided preventive care, then spending will increase in 2021, reducing or eliminating the potential for a shared savings bonus and potentially subjecting ACOs to penalties. Although every community will have experienced these problems to some degree, bonuses and penalties in the Shared Savings Program are based on the relative changes in spending between communities, so different ACOs will likely be affected differently by this.

Suspending the Shared Savings program during the pandemic in order to avoid unfair penalties for ACOs would also prevent ACOs from obtaining shared savings bonuses that they needed to offset the cost of care management or other services they had implemented using their own resources.

Why Shared Savings Programs Are Particularly Problematic for Small Rural Hospitals

Both the general approach and the details of the methodology used by Medicare make the shared savings model particularly problematic for small rural hospitals:

The smallest rural hospitals are too small to participate. A hospital, clinic, or other group of providers is only eligible to participate in the Medicare Shared Savings Program if they will have at least 5,000 assigned Medicare beneficiaries. The majority of counties in the country have less than 5,000 Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries6, which means that even if every one of the beneficiaries living in the county was assigned to the ACO, the ACO would not be large enough to participate.7 80% of small rural hospitals (those with less than $45 million in total expenses) are located in counties with fewer than 5,000 Medicare beneficiaries. In general, the only way for a small rural hospital to participate in an ACO is if a large hospital is also participating or if multiple small rural hospitals and clinics join together to create an ACO that spans a large enough geographic area to ensure that at least 5,000 Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries will be assigned.

There is no additional revenue for the hospital unless the payer determines there have been savings, and there is no permanent change in payment. The shared savings program is just a pay-for-performance system added on top of the standard payment systems. A hospital still receives the same fee for each individual service it delivers; in the Medicare program, a Critical Access Hospital or Rural Health Clinic still receives the same cost-based payment as it would otherwise. If the hospital does receive a shared savings bonus, it is only for one year, and there is no guarantee that the hospital will qualify again the following year. The Medicare Shared Savings Program does nothing to increase payments for existing services to ensure the payments are adequate to cover the cost of delivering those services.

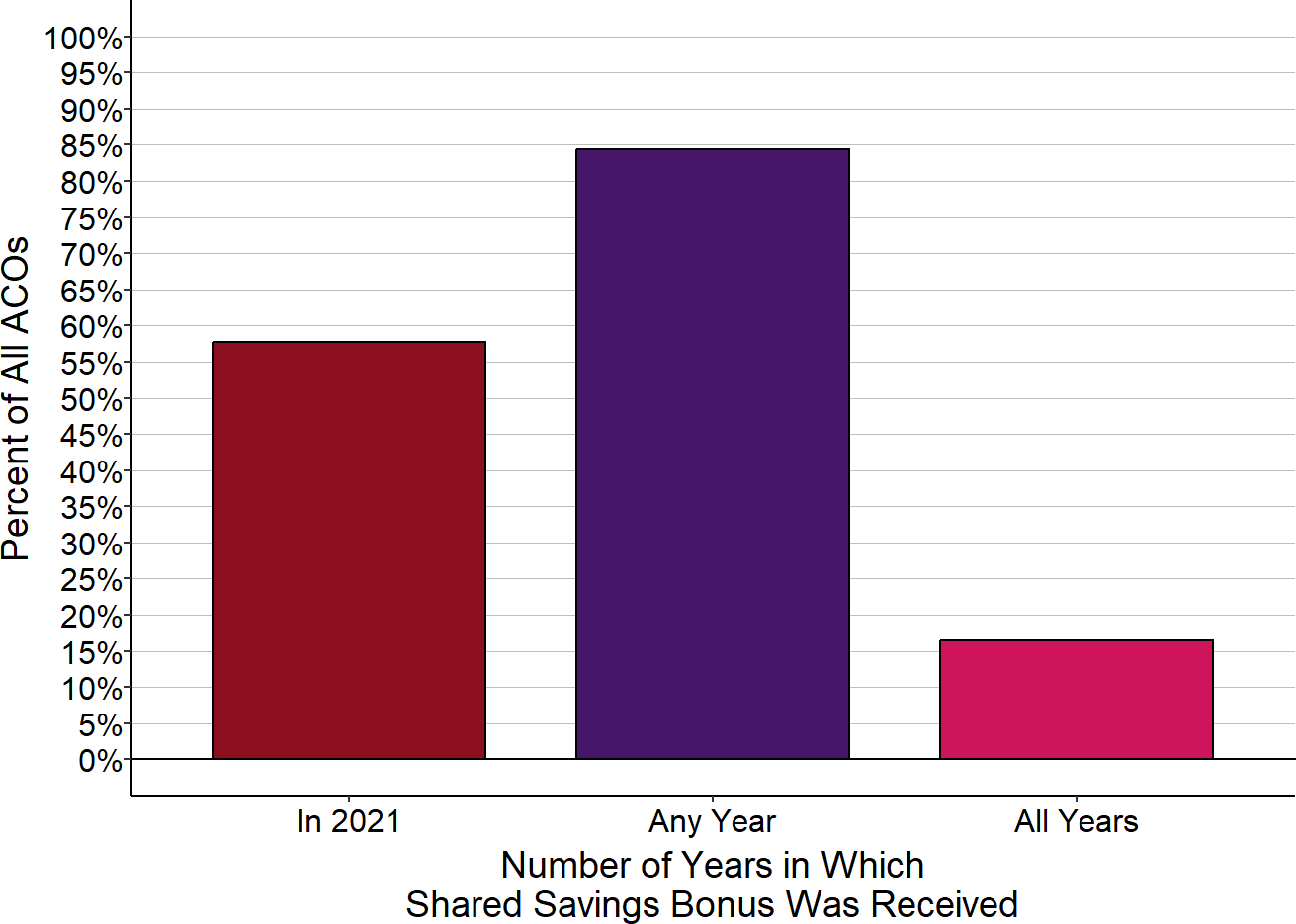

Only about half of ACOs were able to qualify for shared savings payments in 2021, and fewer have qualified in multiple years. As shown below, over 40% of ACOs participating in the Medicare Shared Savings Program did not receive a shared savings bonus in 2021. One-sixth did not achieve a shared savings bonuses in any year they had participated and fewer than 20% had received a shared savings bonus in every year that they participated.8

Figure 2

Shared Savings Bonuses Received by ACOs

in the Medicare Shared Savings Program

Includes only Accountable Care Organizations participating during 2021. “Any year” and “all years” represent 2021 and any prior year in which the ACO was part of MSSP.

It is particularly difficult for small rural ACOs to receive a shared savings payment. There are a number of aspects of the Medicare Shared Savings Program and the methodology it uses to calculate spending and bonuses that can make it much more difficult for an ACO formed by a small rural hospital to qualify for a shared savings bonus, including:

Rates of service utilization are already below average in many counties where small rural hospitals are located. Medicare beneficiaries living in counties served by small rural hospitals have fewer inpatient days, hospital readmissions, laboratory tests, and imaging studies than those living in counties served by larger rural or urban hospitals.9 It is harder for a rural hospital ACO to reduce spending when rates of service utilization are already below average compared to other communities. The Shared Savings Program gives no credit to an ACO for having kept spending low in the past; it only gets credit for reducing spending in the future.

Risk-adjustment can make spending in rural counties appear higher than it really is. The CMS methodology risk-adjusts spending amounts in order avoid penalizing an ACO for higher spending because its patients are sicker. However, the risk-adjustment methodology CMS uses fails to accurately measure the true differences in patients’ health because it uses Hierarchical Condition Category (HCC) scores. HCC scores are only based on past chronic conditions, not acute conditions or new chronic conditions, so there is no adjustment for patients who have injuries, who develop pneumonia or other acute conditions, or who are newly diagnosed with diabetes, cancer, or other serious chronic conditions. Moreover, the risk scores are based only on diagnosis codes that have been recorded on claims forms submitted when services are delivered. Since Critical Access Hospitals are not paid using diagnosis-based DRGs and because Rural Health Clinics receive a single payment for each visit rather than separate fees for individual services, the diagnosis codes recorded in claims files for patients in rural areas are generally not as complete or accurate as those submitted by larger hospitals and primary care practices.10 This can make the rural patients appear less sick than patients in other communities, which in turn makes risk-adjusted spending appear higher, increasing the potential for penalties.

Reducing avoidable services at Critical Access Hospitals does not necessarily create savings for Medicare or shared savings bonuses for the hospital. At most hospitals, a reduction in emergency department visits or hospital readmissions would result in lower spending for Medicare (as well as less revenue for the hospital). However, at small hospitals, a reduction in the number of services delivered may not enable the hospital to eliminate any costs, and because Critical Access Hospitals receive cost-based payment, the hospital may receive the same revenue from Medicare as it did before, making it more difficult to achieve a minimum level of savings.

Increasing patient utilization of primary care services in rural areas can increase spending more than in urban areas. Medicare pays much more for a visit to a Rural Health Clinic operated by a small hospital than it does for visits to primary care practices in urban areas, so if the rural ACO encourages residents to obtain primary care, Medicare spending would likely increase more than it would at ACOs in other areas.

Home care services are less likely to be available in rural areas. One of the primary ways that ACOs have achieved savings is by reducing the use of inpatient rehabilitation services for patients who have been hospitalized. Many patients who currently go to a Skilled Nursing Facility (SNF) following discharge from an acute inpatient stay could instead go home with appropriate home health care and other home supports, and this can not only reduce spending but improve outcomes for many patients. However, home health care is more difficult and expensive to provide in rural areas, so rural ACOs do not have the same home care options available to them that ACOs in urban areas do.

The rural hospital and clinic have little or no control over the services they do not deliver directly. Expensive, frequently-used treatments such as chemotherapy and percutaneous coronary interventions (i.e., stents and angioplasties) represent a large share of total healthcare spending, and so the decisions made about whether to use those treatments on individual patients will have a significant impact on how much spending increases or decreases. Most small rural hospitals and clinics do not deliver these treatments nor do they employ the specialists who order them, so the rural hospital will have limited, if any, ability to control those aspects of spending.

A small number of patients with serious health problems can eliminate any savings. In a large ACO, a small number of patients who need unusually expensive services or an unusually large number of services will only affect total spending by a small amount. In a small ACO, however, even a few patients who need expensive services can eliminate the chance of reaching the minimum level of savings needed to qualify for a shared savings bonus. For example, the rate of new lung cancer diagnoses is about 300 per 100,000 Medicare beneficiaries, which means that in an ACO with 5,000 assigned beneficiaries, there might be an average of 15 new lung cancer cases per year. However, the actual number will likely vary significantly from year to year in a small community. Since treatment for lung cancer can cost as much as $100,000 per patient, if there were 10 new cases in the community in one year and 20 cases the next year, spending would increase by $1 million (10 additional cases x $100,000 per case). That increase would likely cause the total spending attributed to the ACO to increase by 2%.11 Since an ACO with only 5,000 beneficiaries has to reduce the growth in spending by 3.9%, the increased spending on cancer treatment would mean that spending on other services has to be reduced by an average of 6%. This could eliminate the chance of the ACO receiving a shared savings bonus, even though the increase in spending on cancer treatment could not and should not have been prevented by the ACO.

Receiving a shared savings bonus does not necessarily mean the hospital has received more revenue in total. If the rural hospital ACO is able to reduce spending by reducing ED visits, unnecessary hospital admissions, readmissions, inpatient rehabilitation, and other avoidable services, many of those services would have been delivered by the rural hospital itself. In a Shared Savings Program, there is no change in the way the hospital is paid for individual services, so if the hospital delivers fewer fee-based services, it will receive less revenue. That reduction in revenue will count as “savings” for Medicare or other payers, and if the reduction exceeds the Minimum Savings Rate, the hospital may receive a shared savings payment equal to a fraction of the savings. However, by definition, the shared savings payment will be less than the amount the hospital would have been paid for its services, so the net effect will be a reduction in the hospital’s total revenue. This is particularly true for small rural hospitals with swing beds. When large hospitals reduce the use of Skilled Nursing Facilities, the SNFs experience the reduction in revenue, not the hospitals. But in a small rural hospital, the inpatient rehabilitation often occurs in the hospital swing bed, not a separate SNF facility, so if inpatient rehabilitation decreases, the hospital would lose all or part the revenue.12

A shared savings bonus may not offset the higher costs required to manage the ACO. The rural hospital could receive an increase in revenue if there is a sufficient reduction in the number or types of services local residents receive at other hospitals or physician practices that are not part of the ACO. In general, however, in order to achieve that, the hospital that is managing the ACO will need to obtain analytic information on all of the services the assigned beneficiaries are receiving (not just the hospital’s own services), and it will likely need to invest in care management staff and other services in order to try and reduce use of specialty services, readmission rates, ED visits, and other avoidable services. There is no direct funding available through the Shared Savings Program to support the additional costs of doing these things, nor is there any guarantee that if a shared savings bonus is earned, it would be sufficient to cover the additional costs. Consequently, the hospital would have to draw on its own reserves to pay the upfront costs and if it does not qualify for a bonus greater than that investment, its financial situation would be worse.

It is certainly possible for an ACO formed by one or more small rural hospitals to receive shared savings payments that will actually improve their financial margins. However, all of the many factors above make that unlikely, particularly in any consistent way that the hospital could rely on.

Some organizations are encouraging multiple rural hospitals, even hospitals located in different states, to band together to form ACOs that have a large enough number of beneficiaries to qualify for the lowest Minimum Savings Rate and to reduce the chances of having to pay penalties if the ACO is required to accept two-sided risk. However, the bonuses or penalties for each rural hospital would then be dependent on how well all of the other rural hospitals control spending in their communities while maintaining or improving quality. This also creates the potential for a “free-rider” problem – any individual hospital participating in such a large ACO could decide to do nothing at all to reduce spending or improve quality, while still sharing in any benefits produced by the other hospitals.

Figure 3

How Changes in Volume Affect Margins Under Shared Savings/Risk

How Shared Savings Programs Can Harm Patients

Although the primary goal of an Accountable Care Organization should be to improve health care and health outcomes for patients, the primary goal of a shared savings program is to save money for Medicare or other payers:

There are no changes in payments for individual services that would enable the providers in the ACO to deliver new high-value services that would benefit patients.

There is no bonus for an ACO if it successfully improves the quality of care for patients more than other providers, no matter how large the improvement is. The ACO only receives a bonus if it reduces spending compared to other providers by a large amount.

There is no penalty for an ACO that reduces the quality of care; the only penalty occurs if total spending increases.

If an ACO reduces spending sufficiently to qualify for a shared-savings bonus, the bonus will be reduced if its providers deliver lower-quality care than other providers; this is the only “penalty” for poor quality care, and it only exists if the ACO has also reduced spending sufficiently. There is no comparable reward for delivering better quality care; even if the ACO qualifies for a shared savings bonus, the bonus will not be increased regardless of whether the ACO delivers better quality care than others do; the bonus can only be reduced.

Many of the ACOs in the Medicare Shared Savings Program have made a variety of changes in service delivery that have improved care for patients in very desirable ways. However, the ACOs made these changes because the hospitals and physicians who formed the ACO were large enough and had access to enough resources to make investments in better care, not because the Shared Savings Program enabled them to do so. Many hospitals that have formed ACOs have reported that they have actually reduced their financial margins as a result of these changes because the shared savings payments they have received, if any, were less than the costs they incurred to deliver improved services. Small rural hospitals are unlikely to have the ability to do this.

Because of the single-minded focus on achieving savings, a shared savings program creates problematic financial incentives that have the potential to harm rural hospitals, physicians, and other providers that are part of an ACO paid through shared savings:

a financial incentive to withhold services or discourage patients from receiving high cost services. Delivering fewer services to patients will reduce spending, and that reduction in spending is counted as savings whether the patients needed the services or not. As a result, while the shared savings program creates a financial incentive to avoid ordering or delivering unnecessary services, it also creates a financial incentive to avoid ordering and delivering services that patients need. The quality measures in the program do not prevent this because there are no measures applicable to many types of patients and many aspects of care. For example, cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, and other conditions are expensive to treat properly, but there are no measures of whether patients in the ACO who have these conditions are receiving appropriate care. If there is a choice of two drugs to treat a health condition, one of which has a lower cost but is more likely to cause undesirable side effects for patients, an ACO is more likely to qualify for a bonus if its physicians prescribe the lower-cost drug, and no quality measure would be affected if patient side effects increase as a result. In fact, none of the data that are available about ACOs enables patients to determine whether ACOs are achieving savings by reducing unnecessary services versus reducing necessary care.

a financial incentive to avoid providing primary care to patients who have serious health problems. A resident of the community with serious health problems who had not been receiving primary care would likely benefit from receiving primary care services from the hospital’s clinic or a primary care practice that is part of the ACO. However, once the individual begins coming to the clinic or PCP, the patient would be assigned to the ACO, and all of the healthcare spending associated with the services that patient is receiving from any providers would be counted toward the ACO’s spending level. Because of the flaws in the risk adjustment methodology used in the shared savings program, the more patients with serious health problems who are assigned to the ACO, the less likely the ACO will be to qualify for a shared savings bonus and the more likely it will be subject to a penalty under a shared risk agreement.

a financial incentive to identify patients’ health problems but not to treat them. Because spending will appear lower if the ACO’s patients have higher risk scores, an ACO is more likely to qualify for a shared savings bonus if its patients have more diagnosis codes appearing in claims data. ACOs can potentially receive a greater financial return by investing in efforts to improve diagnosis coding than by investing in better services to treat the patients’ health problems.

Greater Risk for Hospitals ≠ Better Quality Care for Patients

The Phase-Out of Shared Savings in Favor of Downside Risk

Although the Medicare Shared Savings Program was designed specifically to achieve savings for Medicare, it actually caused Medicare spending to increase in its first four years. Per-beneficiary spending increased above the benchmark levels in more than one-third of ACOs from 2012-2016. Only about one-third of ACOs reduced spending enough to receive a shared savings bonus, but those bonuses were greater than the small amount net savings CMS received due to the overall changes in spending, so paying the bonuses increased total Medicare spending. In 2017 and 2018, Medicare did save more than it paid out in bonuses, but the net savings was very small – net savings to the Medicare program only amounted to $36 per beneficiary in 2017 and $75 in 2018, less than 1% of total spending.

CMS did not attribute the lack of significant savings in the Shared Savings Program to the many problems in the payment methodology. Instead, CMS said that ACOs did not have enough “financial risk” and announced that the program’s “upside only” track would be phased out. Now, all ACOs will ultimately be required to accept “downside risk,” i.e., to pay penalties if spending increases beyond the benchmark established by CMS.

However, there is no evidence that simply increasing the financial risk for the hospitals, physicians, and other providers in an ACO will result in greater savings for Medicare. Moreover, requiring all ACOs to pay penalties when spending increases by more than arbitrary thresholds will make the program even more problematic for small rural hospitals and rural communities:

Greater financial risk creates greater financial harm for rural hospitals. The factors described above that reduce the likelihood of ACOs receiving shared savings bonuses also increase the likelihood that they will have to pay penalties. Unlike large hospitals, rural hospitals are not making large profits on non-Medicare patients that can be used to pay penalties to Medicare, nor do they have financial reserves that would enable them to afford to pay penalties that are caused by random variations in spending.

Greater financial risk encourages stinting on patient care. The problematic financial incentives in the shared savings program to stint on patient care would be even stronger if a rural hospital is trying to avoid paying a penalty to Medicare rather than merely trying to qualify for a bonus payment.

The Problems with Global Payment Programs

A number of large physician practices, independent practice associations, and health systems have withdrawn from the Medicare Shared Savings Program or have refused to participate at all because of the problematic structure of the program and the fact that it makes no actual changes in the way healthcare providers are paid for services. They have called for Medicare to pay ACOs using a “global payment” or “population-based payment” instead. Many of these organizations already have capitation contracts with Medicare Advantage plans and commercial HMO plans that pay them in similar ways.

In response, CMS has created a new demonstration program called “Direct Contracting” in which entities called “Direct Contracting Entities (DCEs)” can take financial risk for the total Medicare spending on a group of assigned beneficiaries and receive capitation payments instead of fees for some or all of the services they provide.13

Whether one calls this “global payment,” “population-based payment,” “capitation,” or “direct contracting,” and whether one calls the entity receiving the payment a DCE, ACO, or something else, the basic concept is the same:

a group of healthcare providers (the DCE/ACO) receives a monthly payment for each Medicare beneficiary who is assigned to the group;

the providers in the DCE/ACO no longer receive separate fees for the individual services they deliver to the assigned beneficiaries;

if a provider who is not a member of the DCE/ACO delivers a service to one of the beneficiaries who is assigned to the DCE/ACO, that provider is paid a fee for that service by Medicare, but the monthly payments to the DCE/ACO are reduced by the amount of that fee.

as a result, the total amount that Medicare spends on the assigned beneficiaries is equal to the monthly payments to the DCE/ACO to which those beneficiaries are assigned.

This arrangement provides far more flexible payment for the providers in the DCE/ACO than they receive under the Shared Savings Program, since the monthly payments are not tied to how many or what types of services are delivered. However, it also creates greater financial risk for the providers in the DCE/ACO than under the shared savings program. This risk is manageable for a large physician organization or health system that orders and delivers most of the services that the assigned beneficiary receives, but it is not manageable for a small rural hospital and clinic that only order and deliver a fraction of those services.

Moreover, a global payment system not only retains many of the same problems as the shared savings program for both patients and hospitals, it also has some of the same kinds of problems associated with hospital global budgets. Perhaps most importantly, there is no assurance that the global payment amounts will be sufficient to cover the cost of delivering high-quality care to patients either when the program first begins or over time, nor is there any assurance that even if the payments are adequate, patients will actually receive the services they need. Capitation payment systems were widely used in the 1980s but then discontinued in most communities because of these problems.

The risks and problems associated with global payments far outweigh any benefits for small provider organizations. Consequently, global payments are not a solution for the problems facing rural hospitals and their communities.

Footnotes

Section 1899 of the Social Security Act (42 U.S.C. 1395jjj).↩︎

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Shared Savings Program: Shared Savings and Losses and Assignment Methodology. (August 2020).↩︎

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS Finalizes “Pathways to Success,” an Overhaul of Medicare’s National ACO Program, December 21, 2018.↩︎

Under the Medicare Shared Savings Program, a hospital this small would likely have to reduce spending by more than 2% in order to qualify for a shared savings bonus, but for simplicity, the minimum savings rate is assumed here.↩︎

For simplicity, it is assumed here that there is no adjustment in the bonuses or penalties based on quality measures.↩︎

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Geographic Variation Public Use File.↩︎

The Medicare Shared Savings Program only applies to Medicare beneficiaries in “Original Medicare,” not to those who have enrolled in a Medicare Advantage plan, so the number of beneficiaries who could be potentially be assigned to an ACO will often be 20-40% smaller than the total number of Medicare beneficiaries living in the county.↩︎

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Shared Savings Program Accountable Care Organization Public-Use Files.↩︎

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Geographic Variation Public Use File.↩︎

Kosar CM et al. “Association of Diagnosis Coding With Differences in Risk-Adjusted Short-Term Mortality Between Critical Access and Non-Critical Access Hospitals.” JAMA 324(5): 481-487 (2020).↩︎

Average spending per Medicare beneficiary is about $10,000 per year, so with 5,000 assigned beneficiaries, the total spending attributed to the ACO would be about $50 million.↩︎

This would happen even in a Critical Access Hospital receiving cost-based payment if the reduction in rehabilitation services occurs primarily among Medicare beneficiaries.↩︎

Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation. Direct Contracting Model Options.↩︎