Problems and Solutions for Rural Hospitals

The Importance of Rural Hospitals

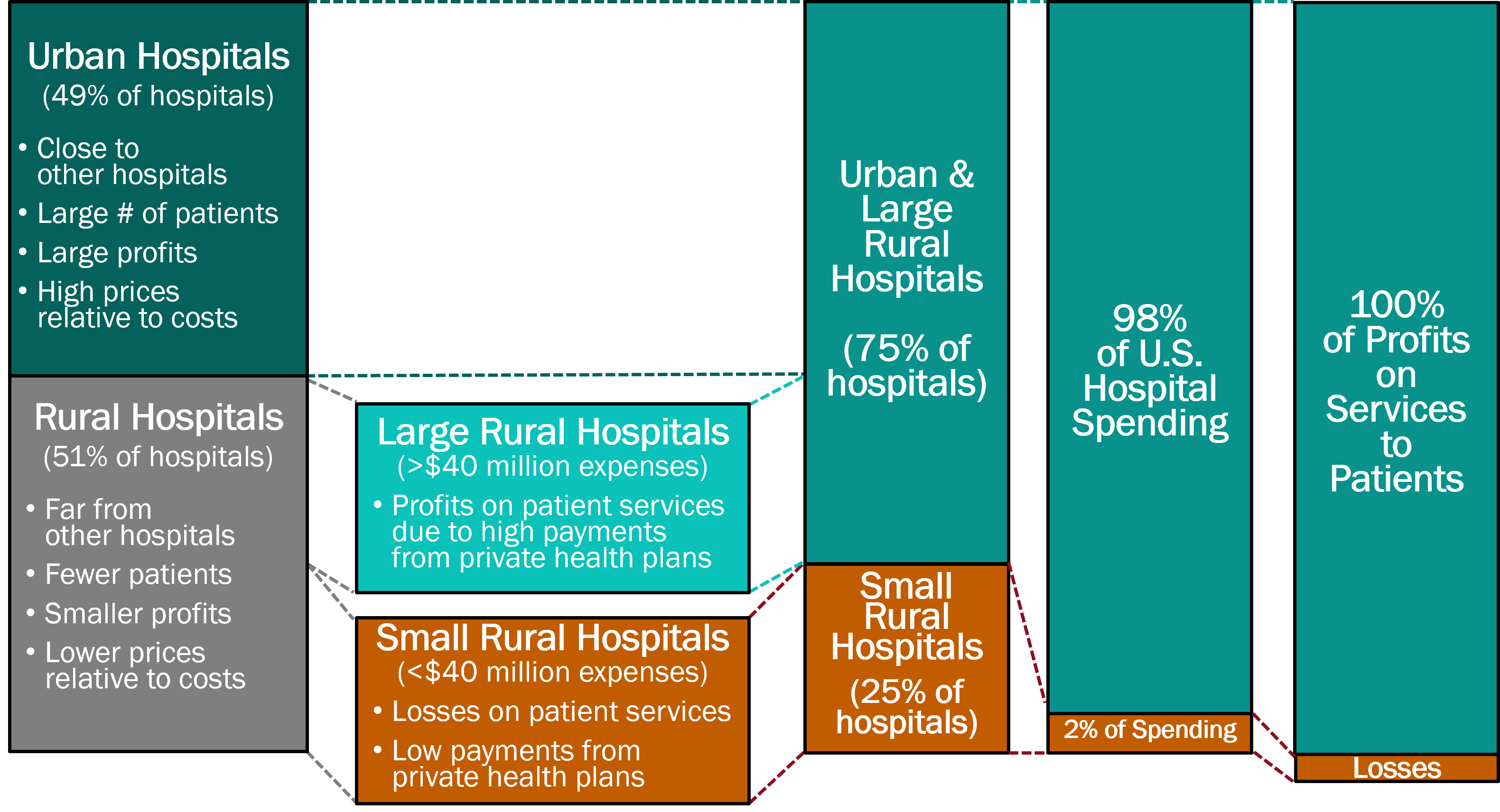

There are two very different types of hospitals in the U.S: (1) small rural hospitals, and (2) urban and large rural hospitals. There are over 1,000 small rural hospitals1, representing nearly one-fourth of all the short-term general hospitals in the country, but they receive less than 3% of total national spending on hospitals.

Small rural hospitals provide most or all of the healthcare services in the small communities they serve. Small rural hospitals deliver not only traditional hospital services such as emergency care, inpatient care, and laboratory testing, but most of them also deliver primary care and inpatient rehabilitation services. The majority of the communities they serve are at least a half-hour drive from the nearest alternative hospital, and many communities have no alternate sources of health care.

The services provided by small rural hospitals are also important for residents of urban areas. Most of the nation’s food supply and energy production comes from rural communities. Farms, ranches, mines, drilling sites, wind farms, and solar energy facilities cannot function without an adequate, healthy workforce, and people are less likely to live or work in rural communities that do not have an emergency department and other healthcare services. Many popular recreation, historical, and tourist sites are located in rural areas, and visitors to those sites need access to emergency services if they have an accident or medical emergency.

The Crisis Facing Rural Healthcare

Small rural hospitals are struggling to survive and rural communities are being harmed. The majority of small rural hospitals are losing money delivering patient services. More than 100 rural hospitals have closed in the past decade, and most of these were small rural hospitals. In most cases, the closure of the hospital resulted in the loss of both the emergency department and other outpatient services, and residents of the community must now travel much farther when they have an emergency or need other healthcare services. This increases the risk of death or disability when accidents or serious medical conditions occur, but it also increases the risk of health problems going undiagnosed or inadequately treated due to lack of access to care.

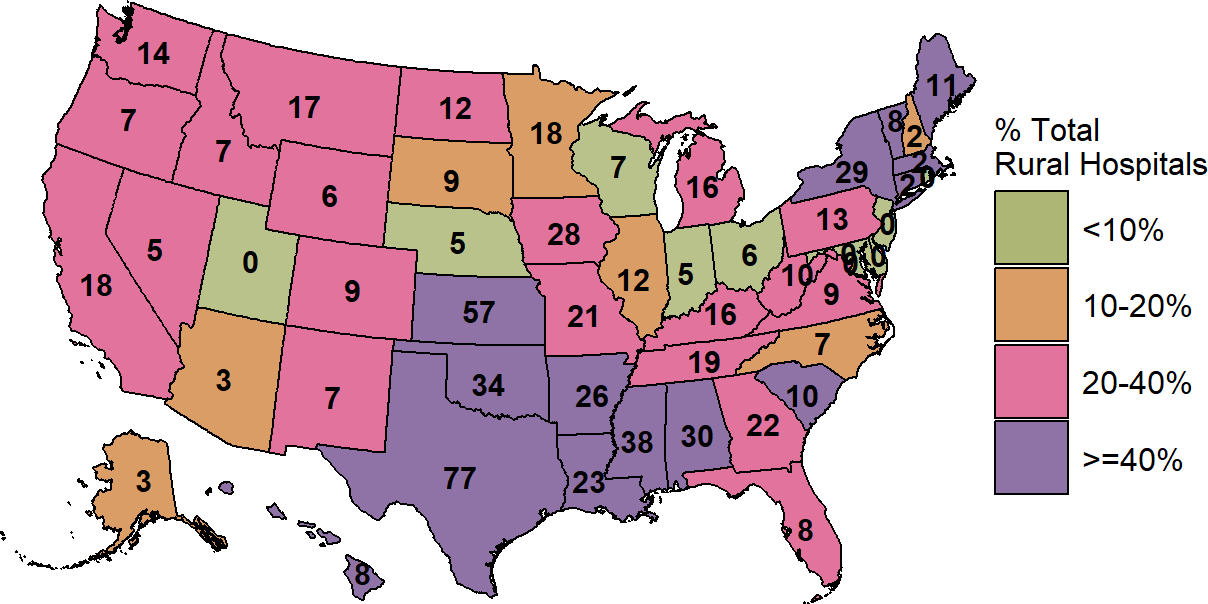

Over 700 rural hospitals – one-third of all rural hospitals in the country – are at risk of closing in the near future, and over 300 of these hospitals are at immediate risk of closing. Most of the at-risk hospitals are small rural hospitals located in isolated communities where loss of the hospital will severely limit access to health care services. Millions of people could be directly harmed if these hospitals close, and people in all parts of the country could be affected through the impacts on workers in agriculture and other industries.

Rural Hospitals at Risk of Closing

Risk of closure is defined as financial losses on patient services during the most recent two years and insufficient financial reserves to allow continued operation unless the hospital receives large grants, local taxes, or other revenues not derived from services to patients.

| RURAL HOSPITALS AT RISK OF CLOSING | ||||||||||||

| State | Hospital Closures Since 2015 |

Inpatient Service Closures (REH)2 |

Open Rural Inpatient Hospitals |

Hospitals With

Losses on Services1 |

Hospitals at

Risk of Closing |

Hospitals at

Immediate Risk |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Percent | Number | Percent | Number | Percent | |||||||

| Kansas | 8 | 3 | 100 | 82 | 82% | 68 | 68% | 30 | 30% | |||

| Mississippi | 3 | 7 | 67 | 38 | 57% | 35 | 52% | 24 | 36% | |||

| Texas | 14 | 4 | 154 | 105 | 68% | 84 | 55% | 23 | 15% | |||

| Alabama | 3 | 3 | 48 | 32 | 67% | 28 | 58% | 22 | 46% | |||

| Oklahoma | 7 | 5 | 74 | 45 | 61% | 48 | 65% | 20 | 27% | |||

| New York | 3 | 3 | 51 | 24 | 47% | 23 | 45% | 15 | 29% | |||

| Tennessee | 10 | 2 | 52 | 20 | 38% | 17 | 33% | 13 | 25% | |||

| Arkansas | 0 | 5 | 47 | 38 | 81% | 31 | 66% | 12 | 26% | |||

| Georgia | 3 | 1 | 73 | 34 | 47% | 25 | 34% | 11 | 15% | |||

| Louisiana | 1 | 1 | 56 | 34 | 61% | 25 | 45% | 11 | 20% | |||

| Missouri | 9 | 2 | 57 | 28 | 49% | 28 | 49% | 10 | 18% | |||

| Pennsylvania | 3 | 0 | 52 | 17 | 33% | 17 | 33% | 9 | 17% | |||

| Illinois | 3 | 0 | 79 | 23 | 29% | 16 | 20% | 8 | 10% | |||

| Indiana | 3 | 0 | 55 | 16 | 29% | 9 | 16% | 8 | 15% | |||

| Washington | 0 | 0 | 45 | 29 | 64% | 19 | 42% | 7 | 16% | |||

| Minnesota | 3 | 1 | 97 | 33 | 34% | 19 | 20% | 6 | 6% | |||

| North Carolina | 6 | 0 | 56 | 13 | 23% | 9 | 16% | 6 | 11% | |||

| West Virginia | 1 | 0 | 34 | 16 | 47% | 13 | 38% | 6 | 18% | |||

| California | 2 | 0 | 59 | 23 | 39% | 16 | 27% | 5 | 8% | |||

| Virginia | 2 | 0 | 31 | 6 | 19% | 8 | 26% | 5 | 16% | |||

| Wisconsin | 0 | 0 | 81 | 19 | 23% | 12 | 15% | 5 | 6% | |||

| Maine | 3 | 0 | 24 | 10 | 42% | 10 | 42% | 4 | 17% | |||

| South Carolina | 3 | 0 | 22 | 7 | 32% | 7 | 32% | 4 | 18% | |||

| Florida | 5 | 0 | 22 | 7 | 32% | 8 | 36% | 3 | 14% | |||

| Michigan | 2 | 1 | 66 | 15 | 23% | 9 | 14% | 3 | 5% | |||

| Montana | 0 | 0 | 53 | 26 | 49% | 16 | 30% | 3 | 6% | |||

| Nebraska | 1 | 1 | 71 | 19 | 27% | 6 | 8% | 3 | 4% | |||

| North Dakota | 0 | 0 | 38 | 27 | 71% | 14 | 37% | 3 | 8% | |||

| Ohio | 1 | 0 | 74 | 13 | 18% | 7 | 9% | 3 | 4% | |||

| Oregon | 0 | 0 | 34 | 12 | 35% | 7 | 21% | 3 | 9% | |||

| South Dakota | 0 | 1 | 48 | 9 | 19% | 6 | 12% | 3 | 6% | |||

| Wyoming | 0 | 0 | 27 | 10 | 37% | 6 | 22% | 3 | 11% | |||

| Colorado | 0 | 0 | 43 | 16 | 37% | 10 | 23% | 2 | 5% | |||

| Connecticut | 0 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 75% | 3 | 75% | 2 | 50% | |||

| Iowa | 2 | 0 | 94 | 19 | 20% | 9 | 10% | 2 | 2% | |||

| Kentucky | 2 | 2 | 69 | 21 | 30% | 15 | 22% | 2 | 3% | |||

| New Hampshire | 0 | 0 | 18 | 7 | 39% | 4 | 22% | 2 | 11% | |||

| New Mexico | 1 | 1 | 27 | 8 | 30% | 8 | 30% | 2 | 7% | |||

| Alaska | 1 | 0 | 16 | 3 | 19% | 2 | 12% | 1 | 6% | |||

| Idaho | 0 | 1 | 27 | 13 | 48% | 10 | 37% | 1 | 4% | |||

| Massachusetts | 0 | 0 | 7 | 4 | 57% | 2 | 29% | 1 | 14% | |||

| Nevada | 1 | 0 | 14 | 6 | 43% | 4 | 29% | 1 | 7% | |||

| Rhode Island | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 100% | 1 | 100% | 1 | 100% | |||

| Vermont | 0 | 0 | 13 | 8 | 62% | 8 | 62% | 1 | 8% | |||

| Arizona | 1 | 0 | 27 | 5 | 19% | 4 | 15% | 0 | 0% | |||

| Delaware | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 33% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | |||

| Hawaii | 0 | 0 | 13 | 10 | 77% | 8 | 62% | 0 | 0% | |||

| Maryland | 1 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | |||

| New Jersey | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | |||

| Utah | 0 | 0 | 22 | 5 | 23% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | |||

| U.S. Total | 108 | 44 | 2,256 | 960 | 43% | 734 | 33% | 309 | 14% | |||

|

1 Rural hospitals that had a negative margin (loss) on patient services in the most recent year available (2024).

2 Conversion to Rural Emergency Hospital (REH) which requires closure of inpatient services. |

||||||||||||

| Data current as of October 2025 | ||||||||||||

The Causes of the Financial Problems at Small Rural Hospitals

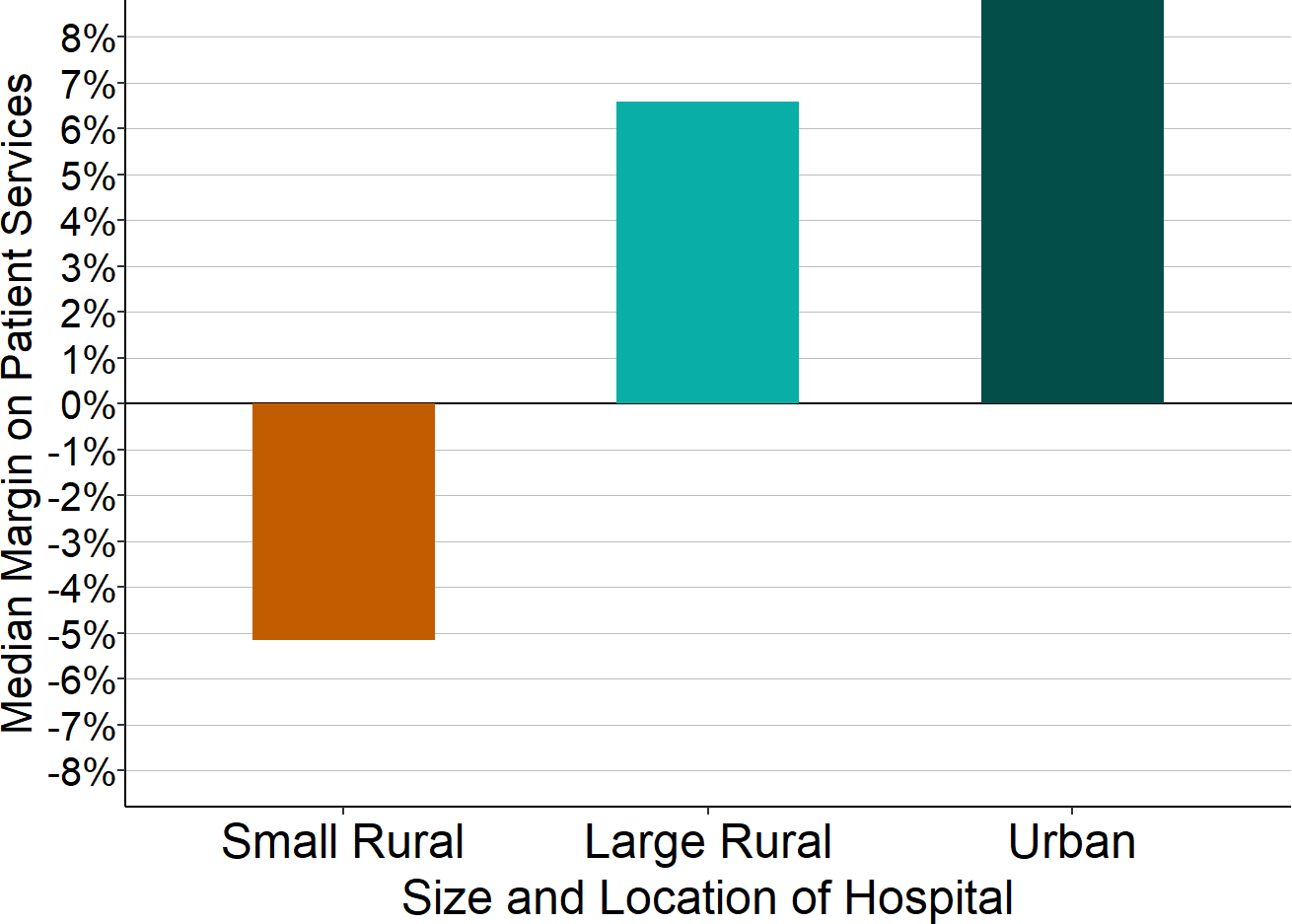

Small rural hospitals are being forced to close because they are not paid enough to cover the cost of delivering care to patients in rural areas. Most small rural hospitals lose money delivering services to patients, while most urban hospitals and larger rural hospitals make profits on patient services.

Median Margin on Patient Services

Sources: CMS Healthcare Cost Report Information System, 2024 Data

A “small” rural hospital is one that has total annual expenses below the median for all rural hospitals.

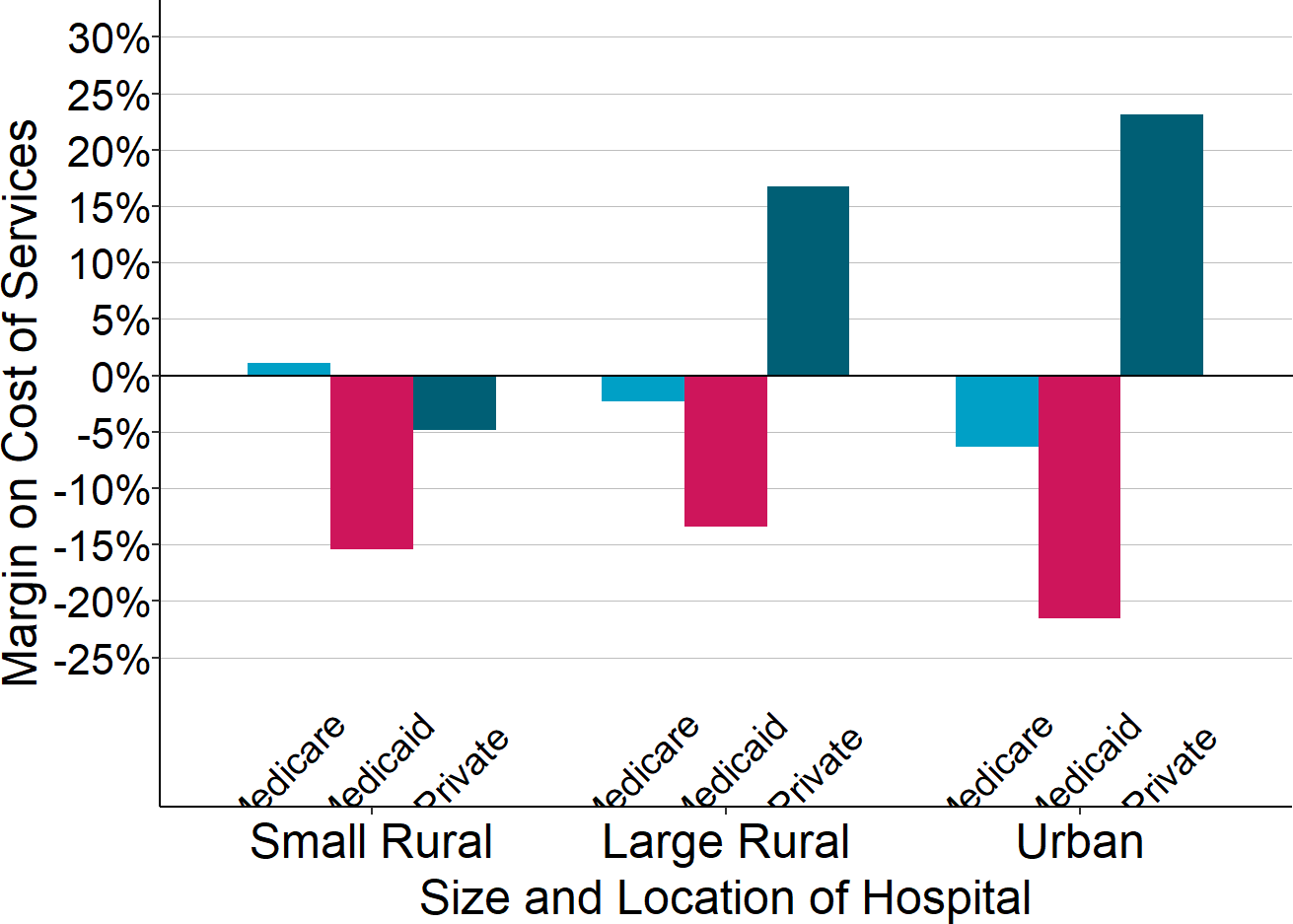

Small rural hospitals lose money on patient services because of inadequate payments from private insurance plans, whereas urban hospitals and larger rural hospitals make large profits on services to patients with private insurance. Most hospitals, regardless of their size, lose money on Medicaid and uninsured patients. However, while large hospitals can offset these losses with the profits they make on patients who have private insurance, small rural hospitals cannot.

Margins on Services to Patients with Medicare, Medicaid, and Private Insurance

Source: CMS Healthcare Cost Report Information System, 2024 data

A “small” rural hospital is one that has total annual expenses below the median for all rural hospitals.

Many small rural hospitals remain open only because they receive significant supplemental funding from state grants or local taxes. In some states, state governments provide grants that reduce or eliminate losses at small rural hospitals, while there is little or no such assistance in other states. Some small rural hospitals are organized as public hospital districts, and residents of these communities tax themselves to offset underpayments by private health plans and Medicaid. There is no guarantee that that these hospitals can continue receiving these large amounts of revenue in the future, and without them, the hospitals would likely be forced to close.

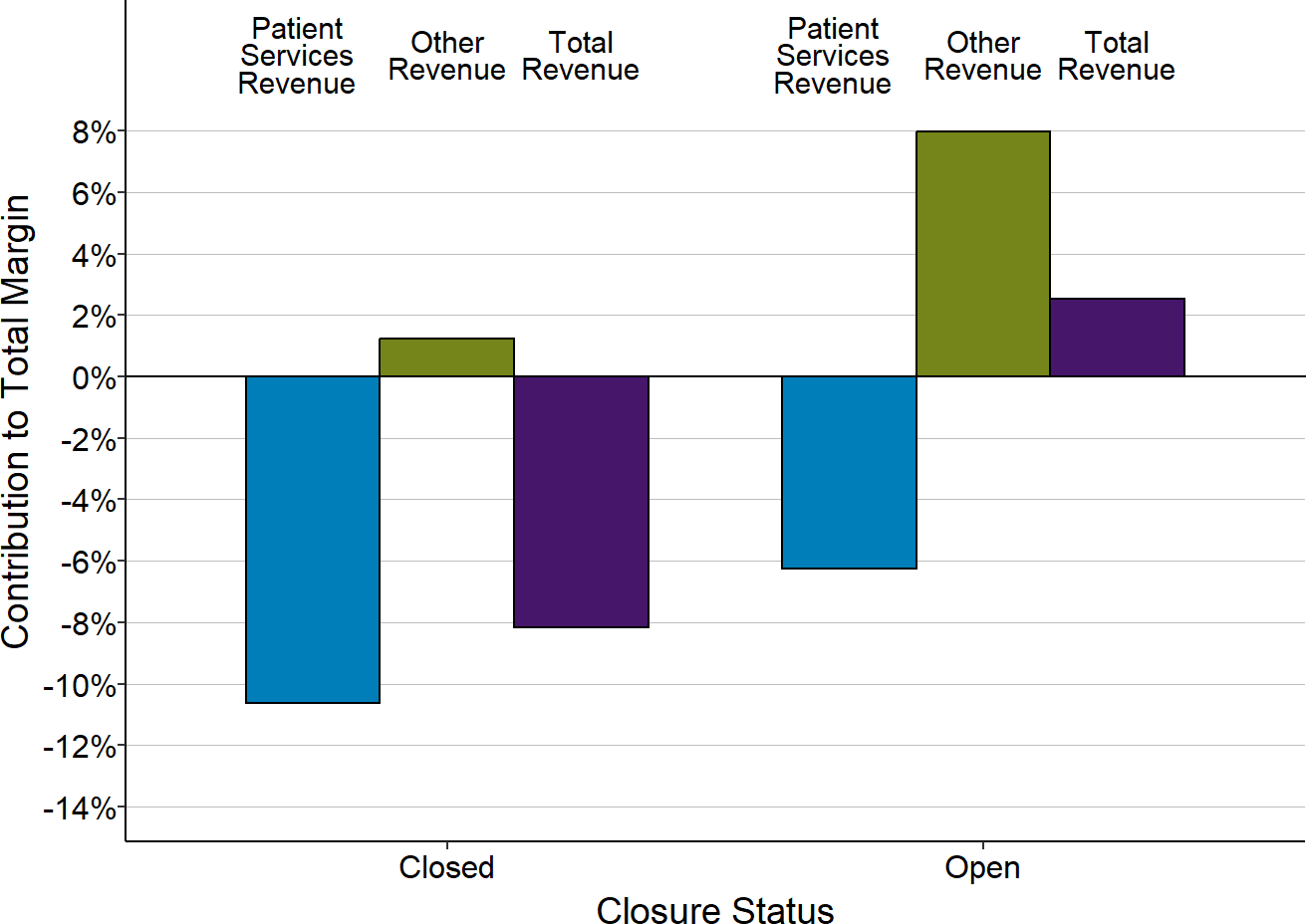

Contributions of Patient Services and Other Revenues

to Total Margins at Closed and Open Small Rural Hospitals

Each bar represents the median value for rural hospitals that (1) have closed since 2015 or (2) remained open in 2025. Only rural hospitals with less than $45 million in expenses are included. The value for each hospital is the median for the three years prior to closure (for hospitals that had closed) or the median for 2024 (for hospitals that were open in 2025) of (a) the dollar margin (i.e., profit or loss) earned on services to patients, (b) the amount of revenue received from sources other than patient serivces, or (c) the total hospital revenue, divided by the hospital’s total expenses. This shows how much revenue from patient services and other sources of revenue contributed to the hospital’s total margin.

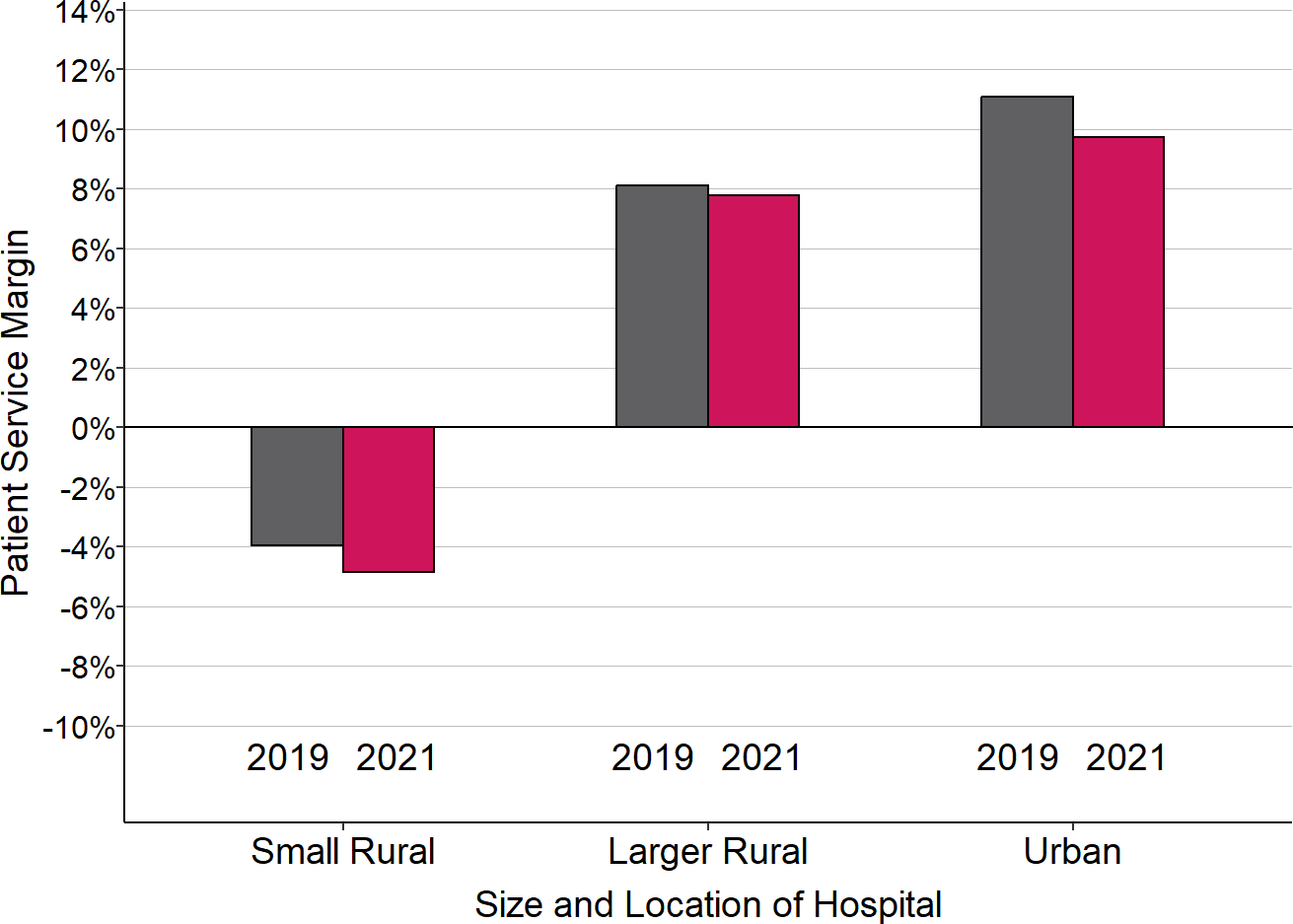

The Impact of the Pandemic on Rural Hospitals

Small rural hospitals had greater losses on patient services during the pandemic. Most rural hospitals experienced lower margins on patient services during the pandemic. Since the majority of small rural hospitals were losing money on patient services prior to the pandemic, the reductions in margins during the pandemic pushed them even further into the red. In contrast, even though larger rural hospitals and urban hospitals also experienced lower margins, most of them continued to generate profits on patient services overall.

Change in Median Margins on Patient Services

“Small Rural” hospitals are rural hospitals with annual expenses less than the median for all rural hospitals. 2020 is defined here as the hospital’s fiscal year that included the March-June 2020 period. 2021 is the year that followed 2020, and 2019 is the year that preceded it.

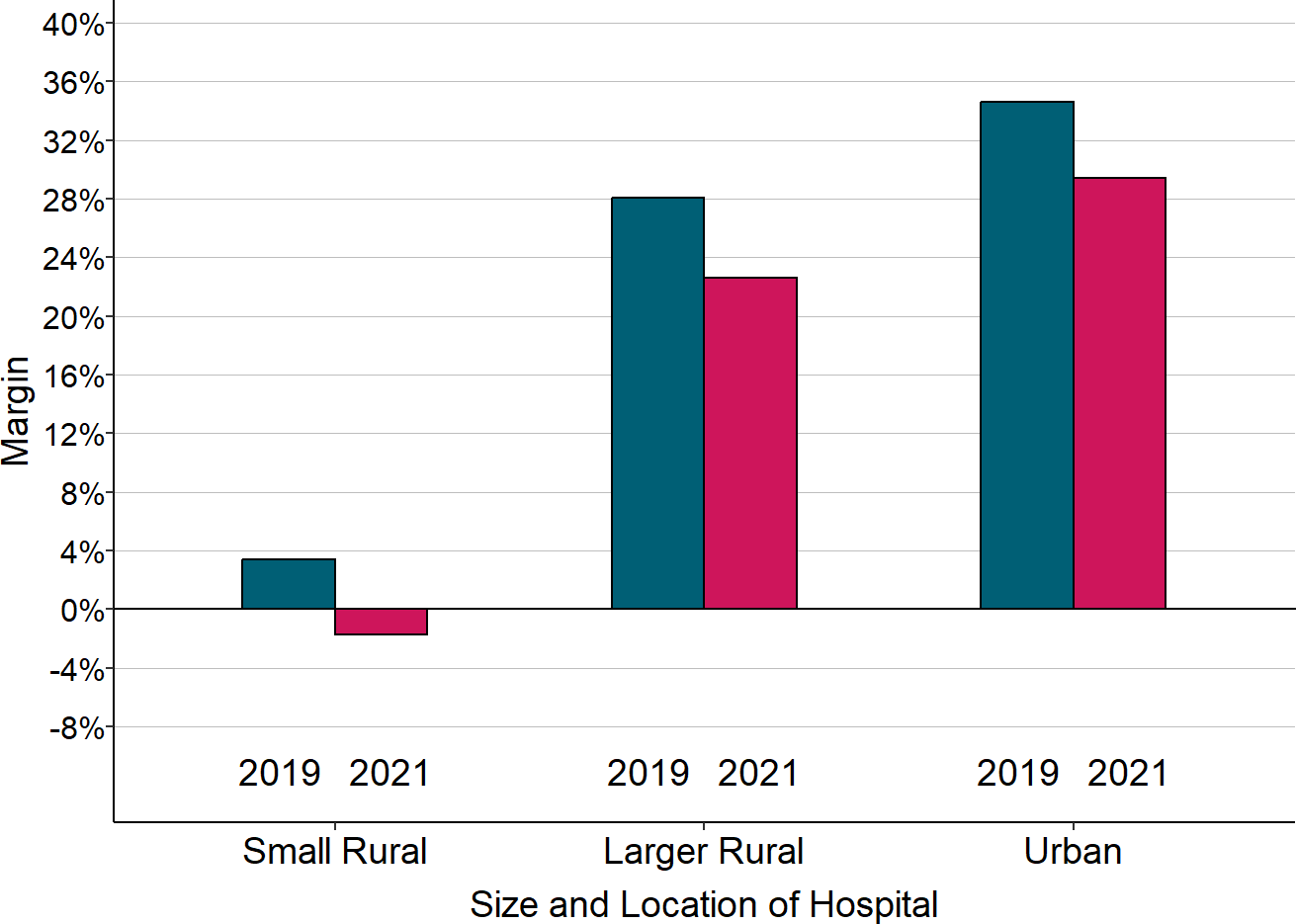

The primary reason overall patient service margins at rural hospitals decreased during the pandemic was higher losses on patients insured by private health plans (including Medicare Advantage plans). The losses on patients insured by private health plans hurt the smallest rural hospitals the most because they were already receiving low payments from private payers prior to the pandemic. Although hospitals of all sizes experienced lower margins during the pandemic on services to patients with private health insurance, the reductions meant that most small rural hospitals lost money providing services to these patients.

Median Margin on Patients With Private Insurance

“Small Rural” hospitals are rural hospitals with annual expenses less than the median for all rural hospitals. 2020 is defined here as the hospital’s fiscal year that included the March-June 2020 period. 2021 is the year that followed 2020, and 2019 is the year that preceded it. The margin shown is the difference between the revenues received from private insurance plans (including Medicare Advantage plans) and the cost of the services delivered to the patients insured by those plans, divided by the cost.

Federal assistance enabled small rural hospitals to continue operating during the pandemic, but because that assistance has now ended, many hospitals could be forced to close. Despite the higher losses on patient services they experienced, only a few rural hospitals closed during the pandemic because of the special federal funding that was available. Most rural hospitals received significant amounts of federal aid that enabled them to continue operating. However, this federal assistance was only temporary. The losses on patient services will likely continue or worsen because of the higher costs that rural hospitals are now facing, and without the extra federal assistance, many hospitals will be at risk of closing.

The Problems With Current Payment Methods

Standard payments for hospital services are not large enough to cover the higher cost of delivering services in small rural communities. The average cost of an emergency room visit, inpatient day, laboratory test, imaging study, and primary care visit is inherently higher in small rural hospitals and clinics than at larger hospitals because there is a minimum level of staffing and equipment required to deliver each of these services regardless of how many patients need to use them. For example, a hospital Emergency Department has to have at least one physician available around the clock in order to respond to injuries and medical emergencies quickly and effectively, regardless of how many patients actually visit the ED. A smaller community will have fewer ED visits, but the cost of the ED will be the same, so the average cost per visit will be higher. Consequently, fees that are high enough to cover the average cost per service at larger hospitals will fail to cover the costs of the same services at small hospitals. Many private health plans pay small rural hospitals less than they pay larger hospitals for the same services, even though the cost per service at the smaller hospitals is inherently higher.

Critical Access Hospital status reduces a small rural hospital’s losses only on services to Original Medicare beneficiaries, and it makes services less affordable for the patients. Most small rural hospitals are classified as Critical Access Hospitals, which enables them to receive cost-based payment for patients with Original Medicare and some Medicaid programs. Although this results in higher payments for Original Medicare patients than the hospital would otherwise receive, it does nothing to reduce losses on uninsured patients and losses on those with other types of insurance, including patients with a Medicare Advantage plan. Moreover, Medicare rules require patients to pay higher cost-sharing amounts in order to receive services at Critical Access Hospitals than at other hospitals, so the higher payments for the hospital can have a negative financial impacts on its patients.

Current methods of payment penalize hospitals for efforts to improve the health of rural residents. If community residents are healthier and need fewer ED visits and other services, the hospital’s revenues will decrease, but the cost of maintaining the essential services will not change, thereby increasing financial losses at the hospital. The same problem occurs under Medicare’s cost-based payment system for Critical Access Hospitals because Medicare’s share of the hospital’s costs decreases if Medicare beneficiaries need fewer services.

The Serious Problems With Commonly Proposed Solutions

Four policies commonly proposed to help rural hospitals are: (1) converting hospitals to “Rural Emergency Hospitals” by eliminating inpatient services; (2) creating a “global budget” for the hospital; (3) paying a hospital “shared savings” bonuses if it reduces total healthcare spending for its patients; and (4) expanding Medicaid eligibility. None of these proposals will solve the problems facing rural hospitals.

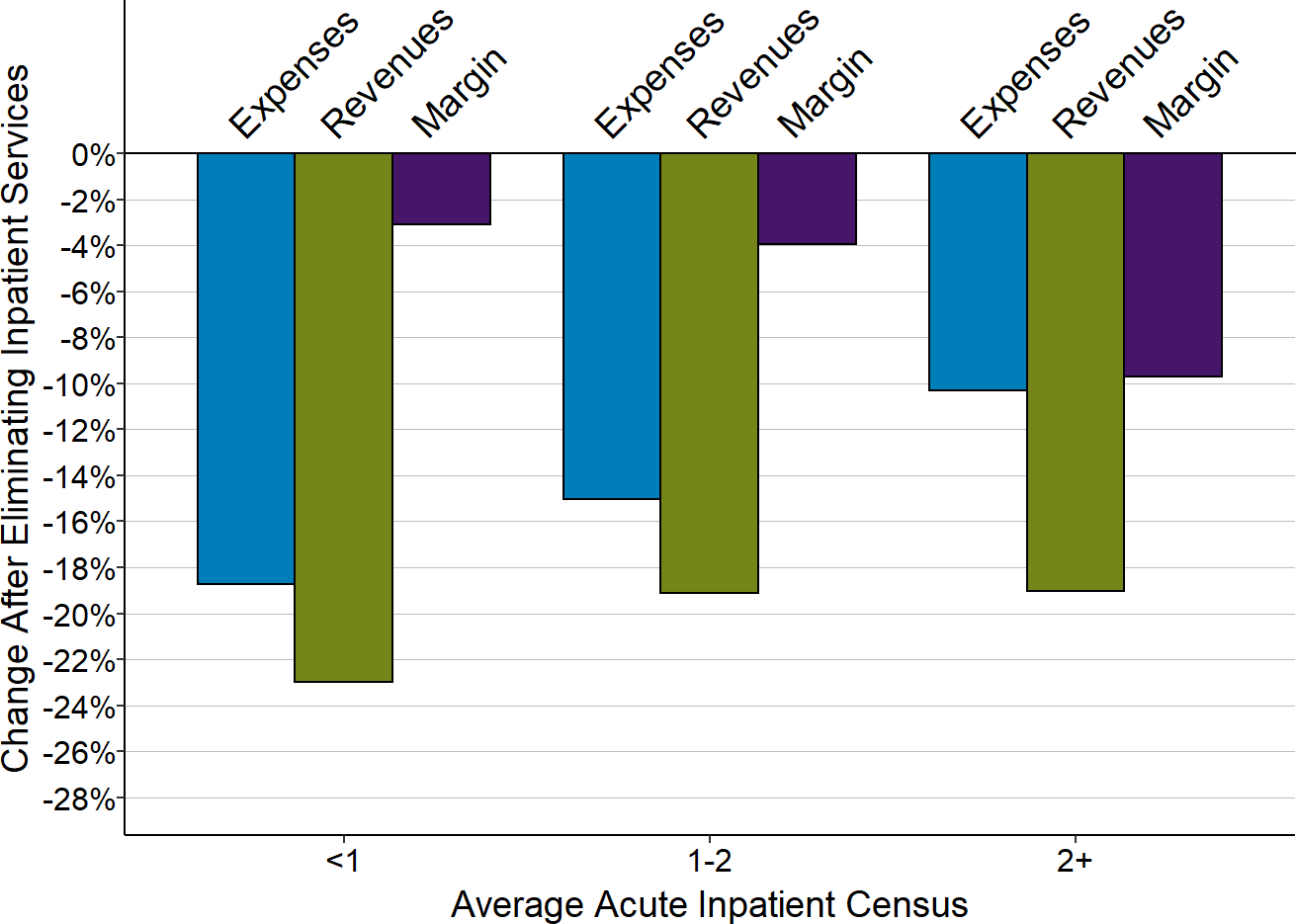

Requiring rural hospitals to eliminate inpatient services would increase their financial losses while reducing access to inpatient care for local residents. Beginning in 2023, hospitals with fewer than 50 beds are allowed to convert to “Rural Emergency Hospital” status if they eliminate their inpatient services. In most cases, the revenues generated by inpatient care at a small rural hospital exceed the direct costs of delivering that care, so even though eliminating the inpatient unit would reduce the hospital’s costs, its revenues could decrease even more, making it worse off financially. In addition, if the hospital converts to a Rural Emergency Hospital, it would no longer be eligible for cost-based payments from Medicare for outpatient services, which could cause additional losses. Although the hospital would receive a supplemental annual payment of about $3 million from Medicare, that may or may not be sufficient to offset these losses. Residents who have a medical condition that requires a short hospital admission could no longer be admitted to the hospital, so they would have to be transferred to another city. Also, local residents who currently receive inpatient rehabilitation and/or long-term nursing care in the hospital’s swing beds could no longer receive those services close to home.

Impacts of Elimination of Inpatient Services

Amounts shown are the medians for the most recent three years available (excluding 2020) based on the estimated reduction in costs and revenues for inpatient care at rural hospitals.

Giving the hospital a global budget would increase losses when patients need more services or the hospital’s costs increase. Most global budget programs have been created in order to limit or reduce payments to hospitals, not to address shortfalls in payment or prevent closure of small rural hospitals. Although hospitals in communities that are experiencing significant population losses or that deliver unnecessary services could benefit from a global budget program in the short run, hospitals that experience higher costs or higher volumes of services due to circumstances beyond their control would likely be harmed, since their revenues would no longer increase to help cover the additional costs.

Although Maryland’s global budget program has been cited as an example of how rural hospitals can benefit from this approach, the smallest rural hospital in Maryland closed in 2020 despite operating under the global budget system.

Under the Pennsylvania Rural Health Model that was created by CMS, hospitals received global budgets that were based on the amount of revenues they received in the past, with no assurance the budgets would be adequate to support the higher cost of delivering essential services in the future. (This project ended in 2024.)

Under demonstration projects developed by the CMS Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation called the Community Health Access and Rural Transformation (CHART) Model and the States Advancing Health Equity Approaches and Development (AHEAD) Model, the “capitated payments” to rural hospitals would have been reduced below the inadequate amounts they currently receive in order to reduce total Medicare spending. (The CHART project was terminated in 2023.)

Access to care for patients can be harmed if budgets are not large enough to support the costs of services, which has led many other countries to modify or replace their global budget systems.

Small rural hospitals would be unlikely to benefit from “shared savings” programs, and most would be harmed by taking on downside risk for total healthcare spending. Most small rural hospitals are unlikely to benefit from forming an Accountable Care Organization (ACO) in order to participate in shared savings programs. It is difficult for small rural ACOs to qualify for shared savings bonuses because the minimum savings threshold is higher than for larger ACOs and because there are fewer opportunities to generate savings. “Downside risk” is especially problematic for small rural hospitals, because they do not deliver and cannot control many of the most expensive services their residents may need, and a requirement that the rural hospital pay penalties when community residents need expensive services at urban hospitals would worsen the rural hospitals’ financial problems.

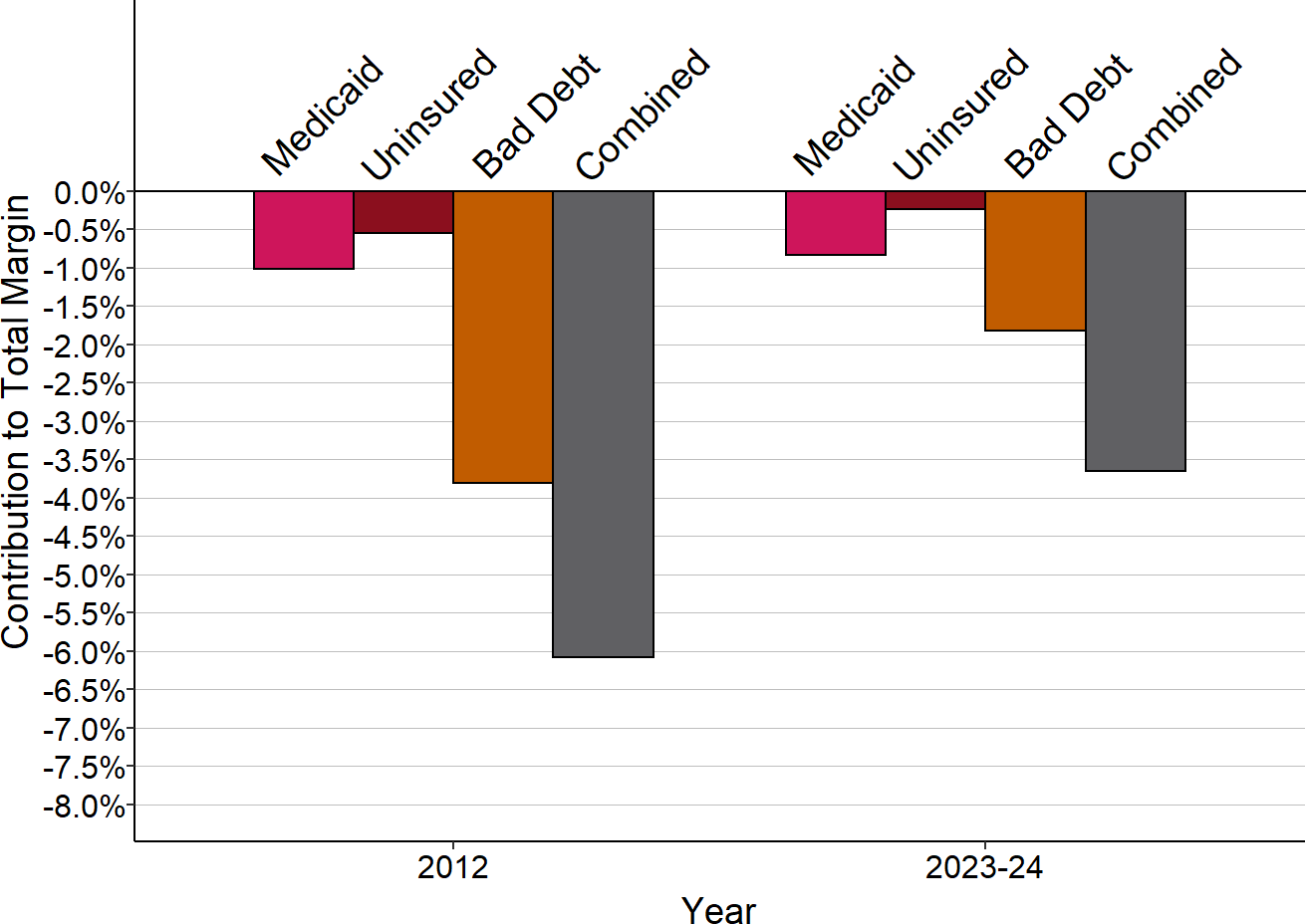

Expansion of eligibility for Medicaid would reduce hospitals’ losses on uninsured patients and bad debt, but it will not reduce the losses on services delivered to Medicaid patients due to low payment amounts. In states that have expanded Medicaid, losses on uninsured charity cases and bad debt decreased, but losses on services to Medicaid patients increased. While the net effect was a reduction in the combined loss from all three categories, the total loss remained high. Health insurance is only of limited value to an individual if there is no hospital or primary care clinic in their community where they can use that insurance because the payments are too low to sustain local services.

Contributions to Small Rural Hospital Margins

in States That Expanded Medicaid

Median for rural hospitals <$45M total expenses. 2012 is pre-expansion, 2024 is post-expansion.

A Better Way to Pay Rural Hospitals

A good payment system for rural hospitals must achieve three key goals:

- Ensure availability of essential services in the community;

- Enable timely delivery of the services patients need; and

- Support delivery of appropriate, high quality, affordable care.

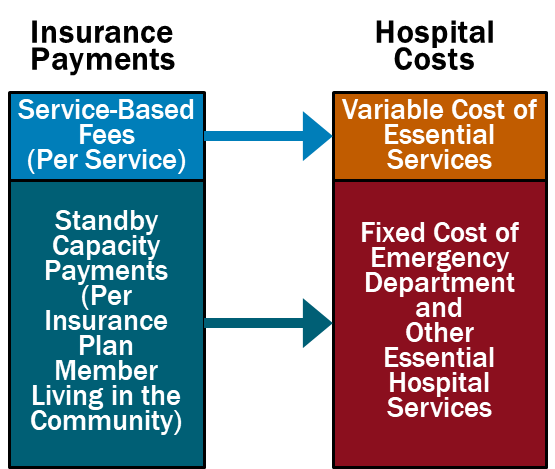

Patient-Centered Payment for rural hospitals can achieve all three goals through the following four components:

Patient-Centered Payment

- Standby Capacity Payments to Support the Fixed Costs of Essential Services. Each health insurance plan (Medicare, Medicaid, Medicare Advantage, and commercial insurance) should pay a Standby Capacity Payment to the rural hospital based on the number of members of that plan who live in the community (regardless of the number of services the patients receive). This ensures that the hospital has adequate revenues to support the minimum standby costs of essential services such as the emergency department, inpatient unit, and laboratory.

- Service-Based Fees for Diagnostic and Treatment Services Based on Variable Costs. Rural hospitals should continue to receive payments from health plans for delivering individual services, but under Patient-Centered Payment, the Service-Based Fees could be much lower than current payments. Since the hospital would receive Standby Capacity Payments to support the fixed costs of essential services, the Service-Based Fees would only need to cover the additional costs incurred when additional services are delivered. This means that if patients stay healthy and need fewer services, the hospital’s revenues and costs will decrease by similar amounts, so the hospital’s margin will not be harmed.

- Accountability for Quality and Spending. In return for receiving adequate payments to support essential services, rural hospitals should take accountability for delivering evidence-based services safely and efficiently.

- Value-Based Cost-Sharing for Patients. TThe amount that a patient has to pay out of pocket to receive necessary services should be affordable for the patient, so patients are not prevented from obtaining the care needed to improve their health.

In addition, rural hospitals that operate Rural Health Clinics or primary care practices need to be paid for primary care services using Patient-Centered Primary Care Payment. The clinic/practice should receive monthly Wellness Care Payments and Chronic Condition Management Payments to support proactive preventive care and chronic disease care delivered by primary care teams, rather than being paid only for office visits with physicians/clinicians, as well as Acute Care Visit Fees when patients experience a new symptom or problem. The payments should provide the clinic/practice with adequate resources and flexibility to help patients stay as healthy as possible and to deliver timely, evidence-based care when the patients experience health problems.

This is a patient-centered approach to payment because it is designed to support the services that patients need, not to increase profits for either hospitals or health insurance plans. Patient-Centered Payment would provide adequate funding to support services in small rural communities without the kinds of problematic incentives to deliver unnecessary services or to stint on care that exist in current payment systems and “value-based” payments.

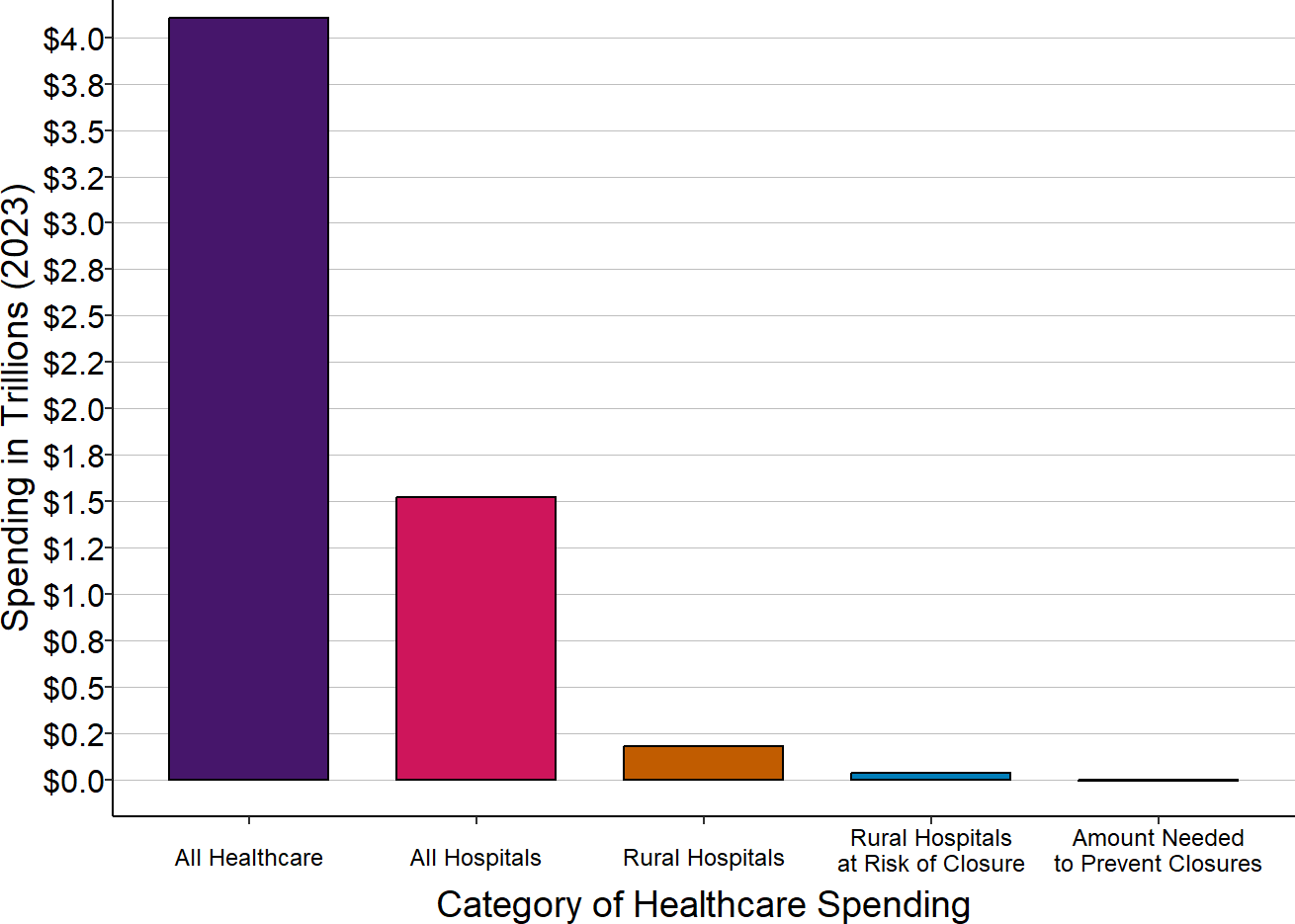

How to Save Rural Hospitals and Strengthen Rural Healthcare

It would cost about $6 billion per year to prevent closures of the at-risk hospitals and preserve access to rural healthcare services, an amount equal to only 1/10 of 1% of total national healthcare spending. No payment system will sustain rural hospitals and clinics unless the amounts of payment are large enough to cover the cost of delivering high-quality care in small rural communities. Because current payments are below the costs of delivering services, an increase in spending by all payers will be needed to keep rural hospitals solvent, but $6 billion is a tiny amount in comparison to the more than $4 trillion currently spent on healthcare and the more than $1.5 trillion spent on all urban and rural hospitals in the country. Moreover, most of the increase in spending will support primary care and emergency care, since these are the services at small rural hospitals where the biggest shortfalls in current payments exist.

Spending Needed to Eliminate Deficits at Rural Hospitals Compared to National Healthcare Spending

Amount needed to prevent closures is the average annual loss, in the most recent three years for which data were available (other than 2020), for hospitals classified as being at risk of closure. National spending on all healthcare services and on hospitals is for 2023. Spending at rural hospitals is for the most recent year available.

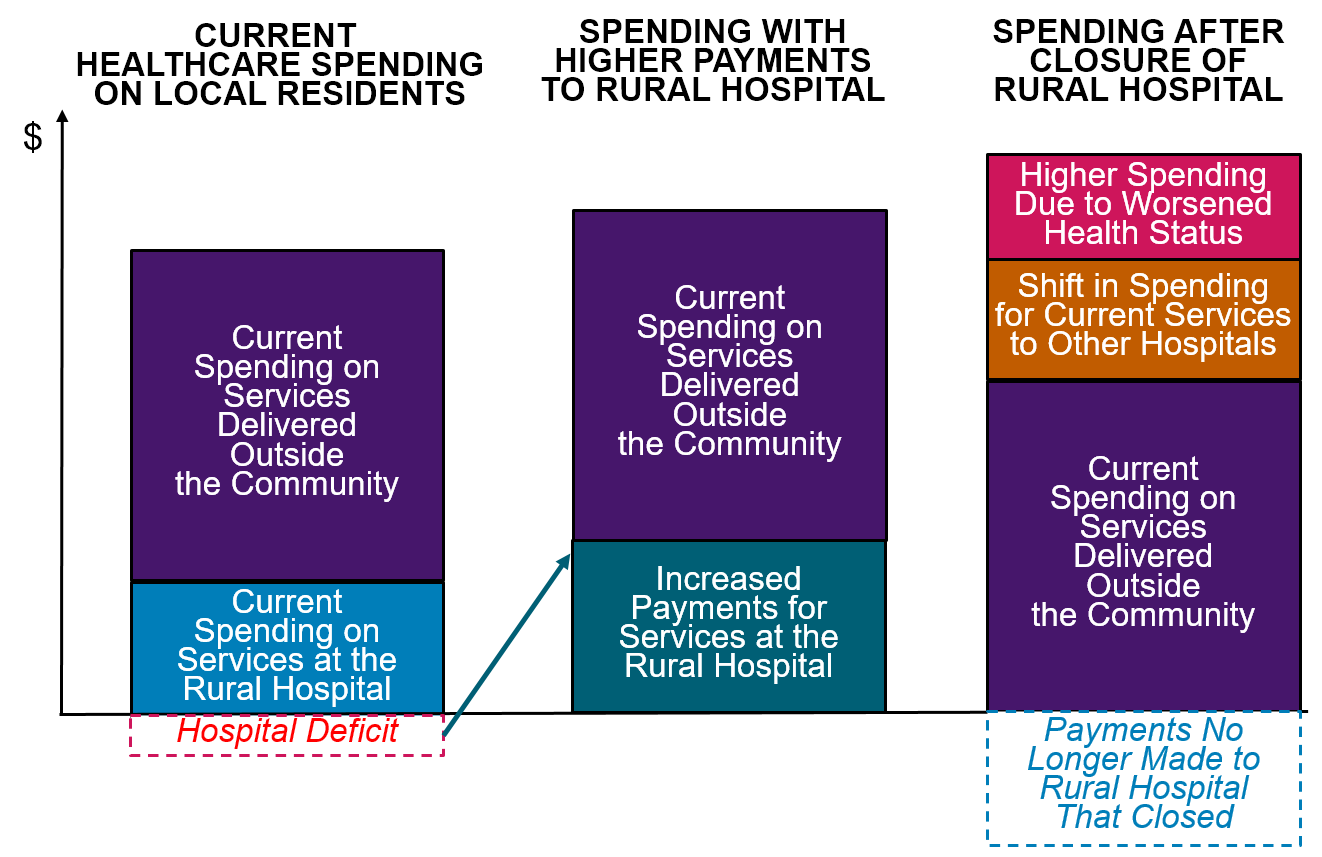

Spending would likely increase even if the hospitals close. The reduced access to preventive care and delays in treatment resulting from a rural hospital closure will cause residents of the community to need even more services in the future. Paying more now to preserve local healthcare services is a better way to invest resources.

Spending Could Increase Even More if Rural Hospitals Are Allowed to Close

Citizens, businesses, local governments, state government, and the federal government must all take action to ensure that every payer provides adequate and appropriate payments for small rural hospitals and clinics:

- Businesses, state and local governments, and rural residents must demand that private health insurance companies change the way they pay small rural hospitals. The biggest cause of negative margins in most small rural hospitals in most states is low payments from private insurance plans and Medicare Advantage plans. Private insurance companies are unlikely to increase or change their payments unless businesses, state and local governments, and residents choose health plans based on whether they pay the local hospital adequately and appropriately.

- State Medicaid programs and managed care organizations need to pay small rural hospitals adequately and appropriately for their services. Expanded eligibility for Medicaid will help more rural residents afford healthcare services, but small rural hospitals cannot deliver the services patients need if Medicaid payments are too low. CMS should authorize states to require Medicaid MCOs to use Patient-Centered Payments and to pay adequately for services at small rural hospitals.

- Congress should create a Patient-Centered Payment program in Medicare for small rural hospitals. Although Medicare is not the primary cause of deficits at small rural hospitals, Medicare needs to pay rural hospitals and clinics in a way that will better sustain services in the long run.

Rural hospitals need to be transparent about their costs, efficiency, and quality, and they should do what they can to control healthcare spending for local residents. In order to support higher and better payments for hospitals, purchasers and patients in rural communities need to have confidence that the hospitals will use the payments to deliver high-quality services at the lowest possible cost, and that the hospitals will proactively identify and pursue opportunities to control healthcare costs for community residents. Small rural hospitals should estimate the minimum feasible costs for delivering essential services using an objective methodology, they should proactively work to improve the efficiency of their services, and they should publicly report on the quality of their care.

Footnotes

A “rural” hospital is a hospital located in an area that is classified as rural by the Health Resources and Services Administration. A “small” rural hospital is one that has total annual expenses below the median for all rural hospitals ($45 million in 2024).↩︎