How to Prevent Rural Hospital Closures

More than 700 rural hospitals – one-third of all rural hospitals in the country – are at risk of closing in the near future. Most of these are small rural hospitals located in isolated communities where loss of the hospital will severely limit access to health care services. Millions of people could be directly harmed if these hospitals close, and people in all parts of the country could be affected through the impacts on workers in agriculture and other industries.

Adequate, appropriate payments for small rural hospitals are essential for preventing closures. Most closures will not be prevented by elimination of inpatient services, creation of global hospital budgets, shared savings programs, technical assistance programs, or one-time grants. The only way to prevent closures and support high-quality rural healthcare is to pay rural hospitals adequately for the services they deliver to patients. A Patient-Centered Payment system is needed that will: (1) ensure availability of essential services in small rural communities; (2) enable safe and timely delivery of the services patients need at prices they can afford to pay; and (3) encourage better health and lower healthcare spending.

It would cost only $6 billion per year to prevent closures of the at-risk hospitals and preserve access to rural healthcare services, an increase of only 1/10 of 1% in total national healthcare spending. The increase in spending needed to prevent rural hospital closures is tiny in comparison to the total amount currently spent on healthcare. Moreover, spending would likely increase even if hospitals close because reduced access to preventive care and prompt treatment will cause residents of the rural communities to need even more services in the future. Paying more now to preserve local services is a better way to invest resources.

Most of the increase in spending will support primary care and emergency care, not inpatient or ancillary services. Available information indicates the biggest causes of losses at most small rural hospitals are underpayments for primary care and emergency services.

Every payer will need to change the way it pays small rural hospitals, but the biggest changes must be made by private health insurance companies. Although most payers are underpaying small rural hospitals, the biggest cause of negative margins in most small rural hospitals in most states is low payments from private insurance plans and Medicare Advantage plans.

Employers and residents in rural communities need to choose private insurance plans that pay their hospitals adequately and appropriately. Most private insurance plans are unlikely to increase or change their payments unless businesses, local governments, and residents choose health plans based on whether they pay the local hospital adequately and appropriately. State insurance departments and state insurance exchanges can help by requiring health plans to disclose their payment methods and amounts for small rural hospitals and by encouraging the plans to use Patient-Centered Payments instead of traditional fees.

Medicaid programs and managed care organizations need to pay rural hospitals adequately and appropriately for their services. Expanding eligibility for Medicaid will help more rural residents afford healthcare services and reduce losses at hospitals from serving uninsured patients. However, small rural hospitals will benefit most from receiving higher Medicaid payments for their services. CMS should authorize states to require Medicaid Managed Care Organizations (MCOs) to use Patient-Centered Payments and to pay adequately for services at small rural hospitals.

Congress should create a Patient-Centered Payment program in Medicare for small rural hospitals. Although Medicare is not the primary cause of deficits at small rural hospitals, creation of a Patient-Centered Payment system in Medicare can serve as a model for other payers. In contrast, Medicare’s “global budget” demonstration program and Rural Emergency Hospital program are unlikely to help most rural hospitals and they could harm many of the smallest hospitals.

Rural hospitals need to be transparent about their costs, efficiency, and quality, and they should do what they can to control healthcare spending for local residents. In order for purchasers and patients in rural communities to support higher and better payments at their hospitals, they need to have confidence that the hospitals will use the payments to deliver high-quality services at the lowest possible cost, and that the hospitals will proactively identify and pursue opportunities to control healthcare costs for community residents. Small rural hospitals should estimate the minimum feasible costs for delivering essential services using an objective methodology, proactively work to improve efficiency of services, and publicly report on the quality of their care.

The Need for Rapid Action to Prevent Closures and Sustain Rural Healthcare

Over the past decade, more than 100 rural hospitals have closed. As a result, the millions of Americans who live in those communities no longer have access to an emergency room, inpatient care, and many other hospital services that citizens in most of the rest of the country take for granted.

In addition, 42 hospitals have eliminated inpatient services in order to qualify for federal grants that are only available for Rural Emergency Hospitals (REHs). Every year, more than 10,000 rural residents had received inpatient care in those hospitals, but now seriously ill individuals in their communities will have to be transferred to a hospital far from home in order to receive the services they need.

Hundreds More Rural Hospitals Could Close in the Near Future

Over 700 rural hospitals – one-third of all rural hospitals in the country – are at risk of closing in the near future. These hospitals are at risk because of the serious financial problems they are experiencing:

- Losses on Patient Services: Health insurance plans do not pay these hospitals enough to cover the cost of delivering services to patients.1 Their losses will likely be greater in the future due to the higher costs that all hospitals, particularly small rural hospitals, are experiencing because of inflation and workforce shortages. Although many of these hospitals have received grants, local tax revenues, or profits from other activities that offset their losses on patient services in the past, there is usually no guarantee that these funds will continue to be available in the future or sufficient to cover higher losses.

- Low Financial Reserves: If the hospitals do not receive grants or other funds to cover losses on services, the hospitals would not have sufficient net assets (including pandemic-related funding but excluding buildings & equipment) to offset the losses on patient services for more than 6-7 years.2

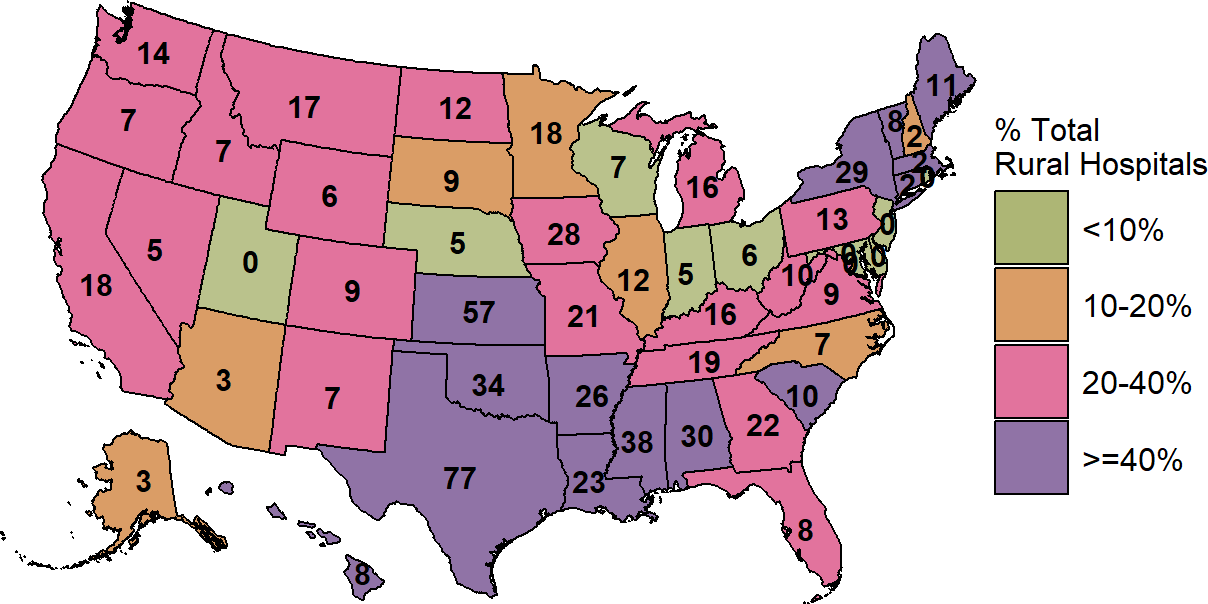

There are hospitals with these characteristics in almost every state. In the majority of states, 25% or more of the rural hospitals are at risk of closing, and in 10 states, 50% or more are at risk.

Figure 1

Rural Hospitals at Risk of Closing

| RURAL HOSPITALS AT RISK OF CLOSING | ||||||||||||

| State | Hospital Closures Since 2015 |

Inpatient Service Closures (REH)2 |

Open Rural Inpatient Hospitals |

Hospitals With

Losses on Services1 |

Hospitals at

Risk of Closing |

Hospitals at

Immediate Risk |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Percent | Number | Percent | Number | Percent | |||||||

| Kansas | 8 | 3 | 100 | 82 | 82% | 68 | 68% | 30 | 30% | |||

| Mississippi | 3 | 7 | 67 | 38 | 57% | 35 | 52% | 24 | 36% | |||

| Texas | 14 | 4 | 154 | 105 | 68% | 84 | 55% | 23 | 15% | |||

| Alabama | 3 | 3 | 48 | 32 | 67% | 28 | 58% | 22 | 46% | |||

| Oklahoma | 7 | 5 | 74 | 45 | 61% | 48 | 65% | 20 | 27% | |||

| New York | 3 | 3 | 51 | 24 | 47% | 23 | 45% | 15 | 29% | |||

| Tennessee | 10 | 2 | 52 | 20 | 38% | 17 | 33% | 13 | 25% | |||

| Arkansas | 0 | 5 | 47 | 38 | 81% | 31 | 66% | 12 | 26% | |||

| Georgia | 3 | 1 | 73 | 34 | 47% | 25 | 34% | 11 | 15% | |||

| Louisiana | 1 | 1 | 56 | 34 | 61% | 25 | 45% | 11 | 20% | |||

| Missouri | 9 | 2 | 57 | 28 | 49% | 28 | 49% | 10 | 18% | |||

| Pennsylvania | 3 | 0 | 52 | 17 | 33% | 17 | 33% | 9 | 17% | |||

| Illinois | 3 | 0 | 79 | 23 | 29% | 16 | 20% | 8 | 10% | |||

| Indiana | 3 | 0 | 55 | 16 | 29% | 9 | 16% | 8 | 15% | |||

| Washington | 0 | 0 | 45 | 29 | 64% | 19 | 42% | 7 | 16% | |||

| Minnesota | 3 | 1 | 97 | 33 | 34% | 19 | 20% | 6 | 6% | |||

| North Carolina | 6 | 0 | 56 | 13 | 23% | 9 | 16% | 6 | 11% | |||

| West Virginia | 1 | 0 | 34 | 16 | 47% | 13 | 38% | 6 | 18% | |||

| California | 2 | 0 | 59 | 23 | 39% | 16 | 27% | 5 | 8% | |||

| Virginia | 2 | 0 | 31 | 6 | 19% | 8 | 26% | 5 | 16% | |||

| Wisconsin | 0 | 0 | 81 | 19 | 23% | 12 | 15% | 5 | 6% | |||

| Maine | 3 | 0 | 24 | 10 | 42% | 10 | 42% | 4 | 17% | |||

| South Carolina | 3 | 0 | 22 | 7 | 32% | 7 | 32% | 4 | 18% | |||

| Florida | 5 | 0 | 22 | 7 | 32% | 8 | 36% | 3 | 14% | |||

| Michigan | 2 | 1 | 66 | 15 | 23% | 9 | 14% | 3 | 5% | |||

| Montana | 0 | 0 | 53 | 26 | 49% | 16 | 30% | 3 | 6% | |||

| Nebraska | 1 | 1 | 71 | 19 | 27% | 6 | 8% | 3 | 4% | |||

| North Dakota | 0 | 0 | 38 | 27 | 71% | 14 | 37% | 3 | 8% | |||

| Ohio | 1 | 0 | 74 | 13 | 18% | 7 | 9% | 3 | 4% | |||

| Oregon | 0 | 0 | 34 | 12 | 35% | 7 | 21% | 3 | 9% | |||

| South Dakota | 0 | 1 | 48 | 9 | 19% | 6 | 12% | 3 | 6% | |||

| Wyoming | 0 | 0 | 27 | 10 | 37% | 6 | 22% | 3 | 11% | |||

| Colorado | 0 | 0 | 43 | 16 | 37% | 10 | 23% | 2 | 5% | |||

| Connecticut | 0 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 75% | 3 | 75% | 2 | 50% | |||

| Iowa | 2 | 0 | 94 | 19 | 20% | 9 | 10% | 2 | 2% | |||

| Kentucky | 2 | 2 | 69 | 21 | 30% | 15 | 22% | 2 | 3% | |||

| New Hampshire | 0 | 0 | 18 | 7 | 39% | 4 | 22% | 2 | 11% | |||

| New Mexico | 1 | 1 | 27 | 8 | 30% | 8 | 30% | 2 | 7% | |||

| Alaska | 1 | 0 | 16 | 3 | 19% | 2 | 12% | 1 | 6% | |||

| Idaho | 0 | 1 | 27 | 13 | 48% | 10 | 37% | 1 | 4% | |||

| Massachusetts | 0 | 0 | 7 | 4 | 57% | 2 | 29% | 1 | 14% | |||

| Nevada | 1 | 0 | 14 | 6 | 43% | 4 | 29% | 1 | 7% | |||

| Rhode Island | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 100% | 1 | 100% | 1 | 100% | |||

| Vermont | 0 | 0 | 13 | 8 | 62% | 8 | 62% | 1 | 8% | |||

| Arizona | 1 | 0 | 27 | 5 | 19% | 4 | 15% | 0 | 0% | |||

| Delaware | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 33% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | |||

| Hawaii | 0 | 0 | 13 | 10 | 77% | 8 | 62% | 0 | 0% | |||

| Maryland | 1 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | |||

| New Jersey | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | |||

| Utah | 0 | 0 | 22 | 5 | 23% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | |||

| U.S. Total | 108 | 44 | 2,256 | 960 | 43% | 734 | 33% | 309 | 14% | |||

|

1 Rural hospitals that had a negative margin (loss) on patient services in the most recent year available.

2 Conversion to Rural Emergency Hospital (REH) which requires closure of inpatient services. |

||||||||||||

| Data current as of January 2026 | ||||||||||||

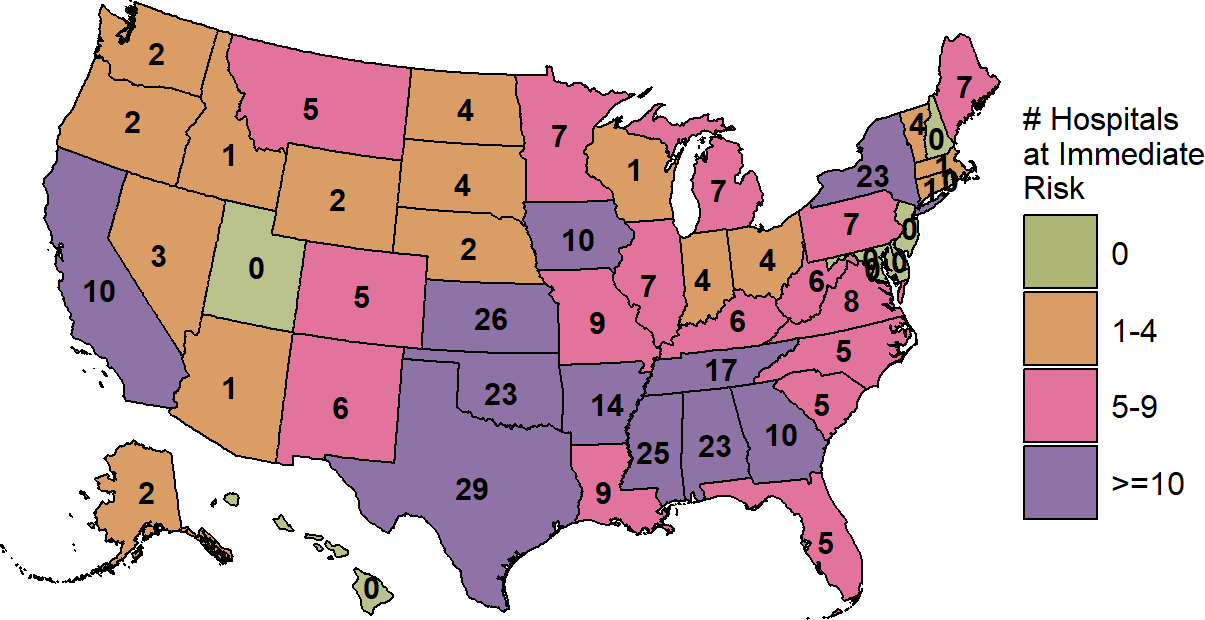

Many Rural Hospitals Are at Immediate Risk of Closing

More than 300 of these hospitals are at immediate risk of closing because of the severity of their financial problems:

- Inadequate Revenues to Cover Expenses. These hospitals have lost money delivering patient services over a multi-year period (excluding the first year of the pandemic), and they do not receive sufficient funds from other sources to cover those losses.

- Very Low Financial Reserves. The hospitals have more debts than assets, or the hospitals’ net assets (excluding buildings & equipment) could offset their losses for at most 2-3 years.

Figure 2

Rural Hospitals at Immediate Risk of Closing

Most Rural Hospitals at Risk of Closing Are in Isolated Rural Communities

Almost all of the rural hospitals that are at immediate or high-risk of closure are in isolated rural communities. Almost all are at least a 20-minute drive away from the next-closest hospital, and over half are more than 30 minutes away. In many cases, the closest hospital is also a hospital that is struggling financially.

When there is only one hospital in the community and the next-closest hospital is many miles away, closure of the hospital means that the community residents have no ability at all to receive emergency or inpatient care without traveling long distances. Maintaining timely access to emergency care and adequate capacity for inpatient care in small rural communities is particularly important when severe and unexpected events occur. The 2020 pandemic clearly demonstrated the value of having hospitals with standby capacity in both rural and urban areas, but similar issues arise on a smaller scale every year with hurricanes, wildfires, influenza outbreaks, and other emergencies.

The impact is much greater than just loss of access to an Emergency Department and inpatient care, however. In many small rural communities, the hospital is often the only place where residents can get laboratory tests or imaging studies, and it may be the only or principal source of primary care in the community. When one of these rural hospitals closes, the community can effectively lose its entire healthcare system, not just a hospital.

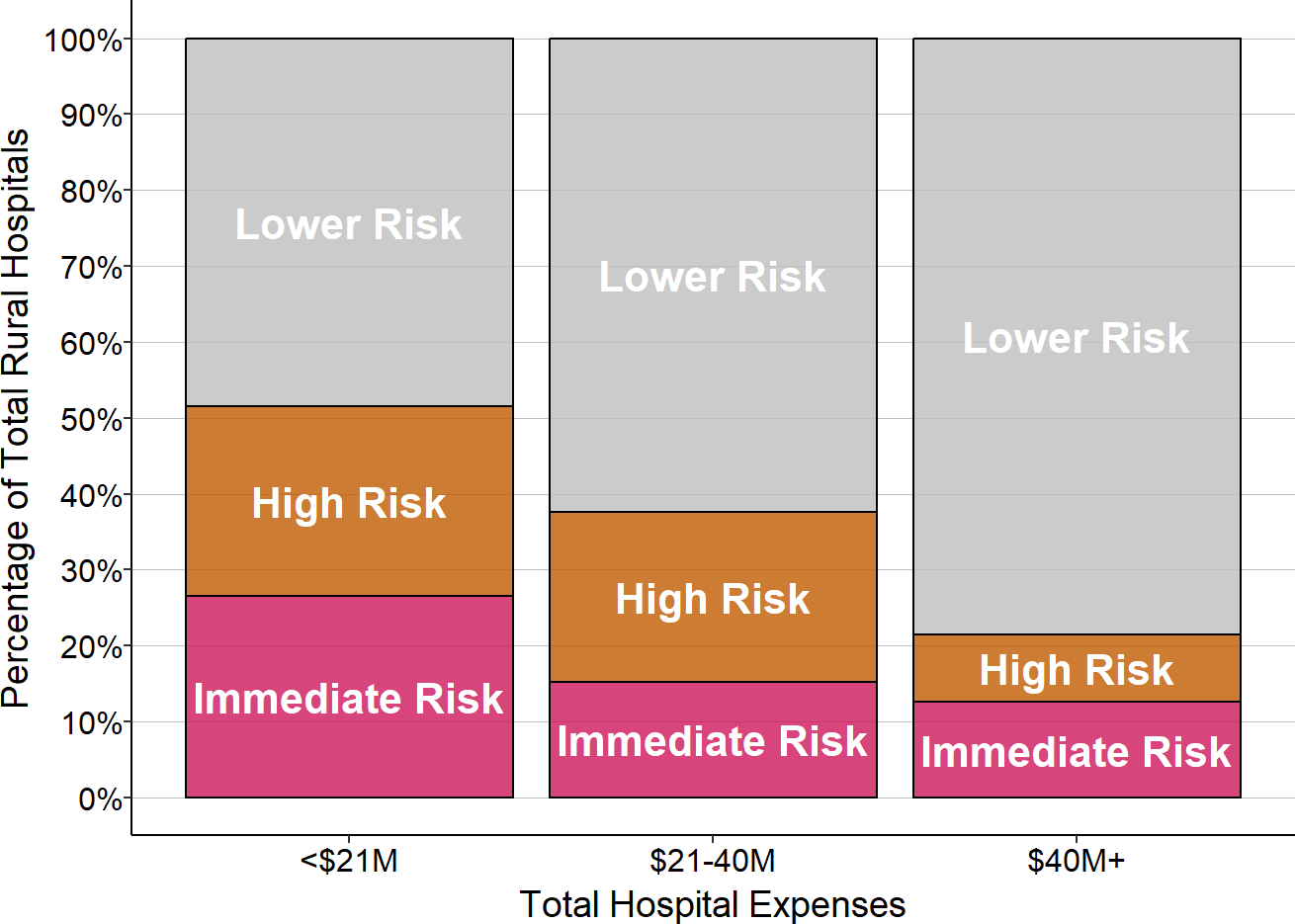

The Risk of Closure is Highest for the Smallest Rural Hospitals

Small rural hospitals are at much higher risk of closure than larger rural hospitals. Almost half of all rural hospitals with less than $45 million in total annual expenses are at risk of closure, and one-sixth are at immediate risk of closure. The majority of hospitals at risk of closure are small rural hospitals.

Figure 3

Risk of Closure in Small vs. Large Rural Hospitals

Rural Hospital Closures Affect Everyone, Not Just Rural Residents

Rural hospital closures affect not only the residents of rural communities, but also people who live in urban areas. The entire nation depends on rural communities to supply food, energy, and recreation, and the continued viability of those industries depends on whether their workers and families have access to adequate healthcare services. The 2020 pandemic proved that health problems in rural communities can lead to food shortages in urban areas.

The rural hospitals that are risk of closing are located in counties that produced over $170 billion in agricultural products in 2017, representing nearly one-fourth of the nation’s agricultural production. If large numbers of these hospitals are allowed to close, people everywhere could be harmed.

The Need for a Better Payment System for Rural Hospitals

What Will Not Solve The Problem

Although there is growing awareness and concern about the problem of rural hospital closures, most of the policies and programs that have been proposed or implemented will not solve the problem, and in some cases, they could make things worse:

- Creating “Rural Emergency Hospitals.” Requiring rural hospitals to eliminate inpatient services would increase their financial losses while reducing access to inpatient care for local residents. Residents of rural communities would have had even more difficulty finding a hospital bed during the pandemic if their hospital had been converted to a Rural Emergency Hospital.

- Expanding Medicaid Eligibility. Making more patients eligible for Medicaid would help low-income patients afford better care and it would reduce a portion of hospitals’ losses on uninsured patients and bad debt. However, uninsured patients are not the primary cause of losses at most rural hospitals; most losses are caused by low payments for patients who have insurance.

- Increasing Medicare payments. An increase in Medicare payments, such as eliminating the 2% sequestration reduction, would be beneficial for rural hospitals, but this would only increase the margin at a typical rural hospital by a small amount. The biggest cause of losses at most small rural hospitals is low payments from private health plans, not Medicare.3

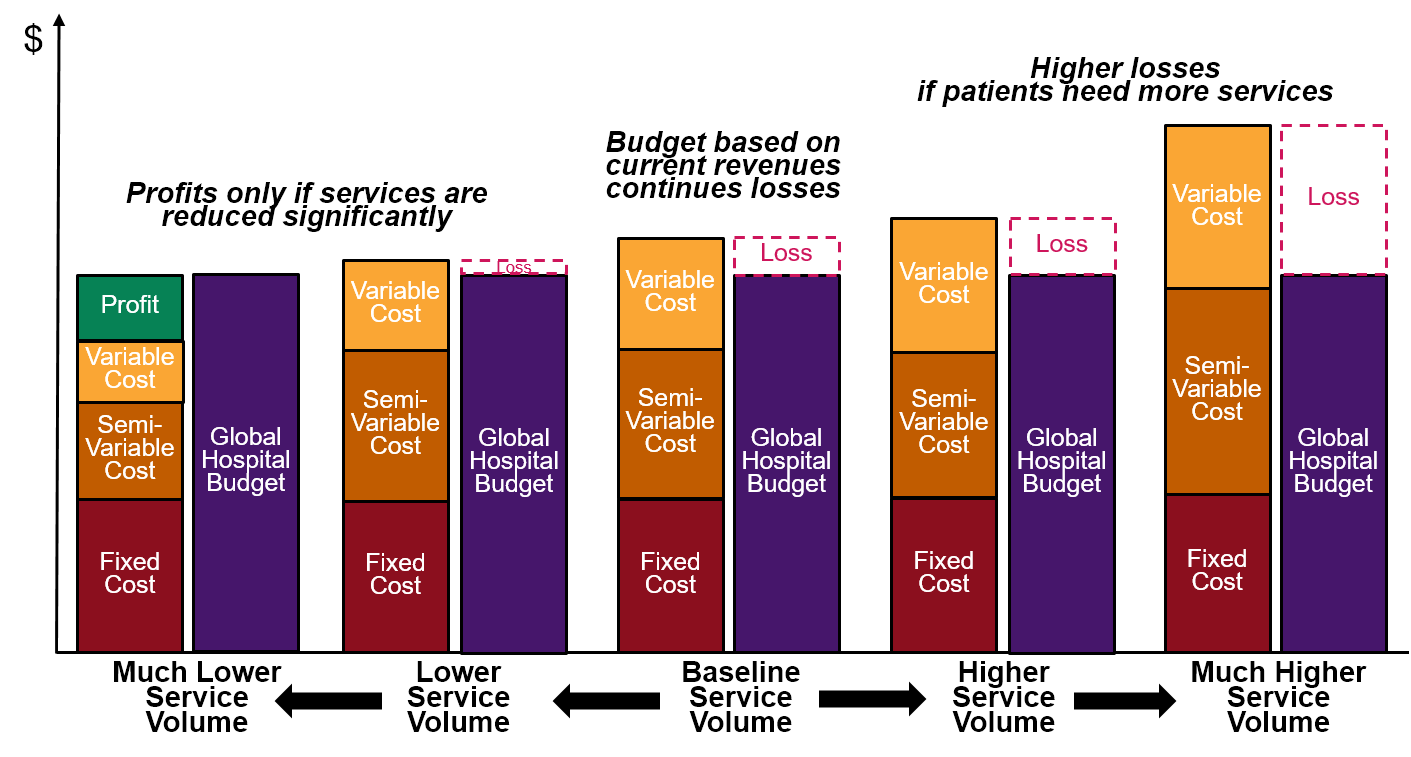

- Creating Global Hospital Budgets. Giving a hospital a fixed budget could protect a hospital from losses in revenues due to lower service volume, but it does nothing to address the increases in costs that most hospitals are currently facing, and it would prevent hospitals from delivering new services their communities need.

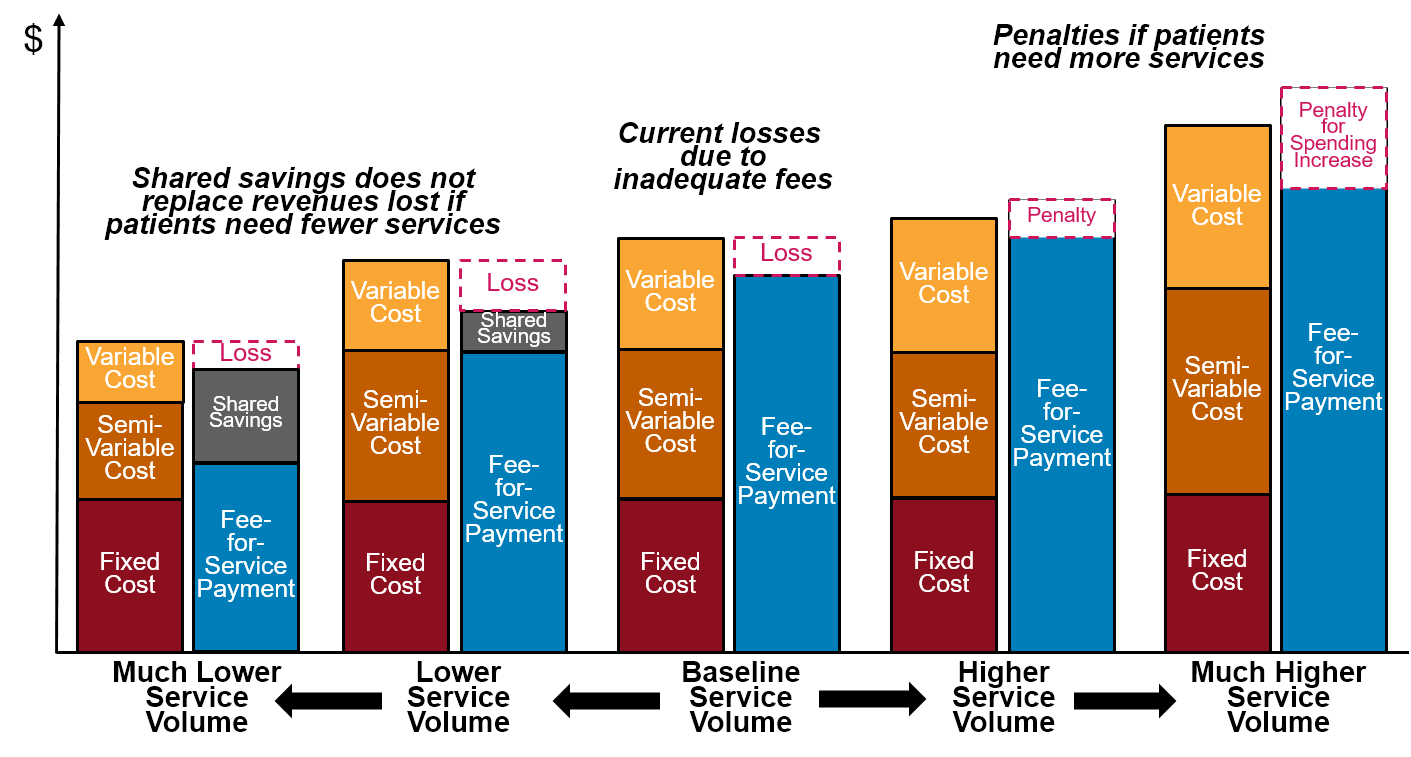

- Shared Savings and Risk-Based Payments. The primary goal of these and most other current “value-based payment” programs is to reduce spending for payers, not to provide adequate financial support for rural hospitals. It costs more per person to provide high-quality care in a small rural community than in larger communities, but most value-based payment programs penalize small hospitals because of that, even if the hospital is operating as efficiently as possible and the quality of care is high. Moreover, most current value-based payment programs are specifically designed for very large numbers of patients, not the small populations in rural communities.

- Technical Assistance Programs. The financial losses at rural hospitals are primarily due to the fact that the payments they receive from private and public payers are not adequate to support the costs of the services they provide, not because they deliver services inefficiently. No amount of technical assistance can help a hospital unless it can receive revenues that are at least as much as the minimum cost of delivering essential services.

What Will Solve the Problem

In order for the residents of rural communities to receive affordable, high-quality healthcare, the payments from health insurance plans to small rural hospitals need to achieve three goals. The payments must:

- Ensure availability of essential services in the community;

- Enable timely delivery of the services patients need; and

- Support delivery of appropriate, high quality, affordable care.

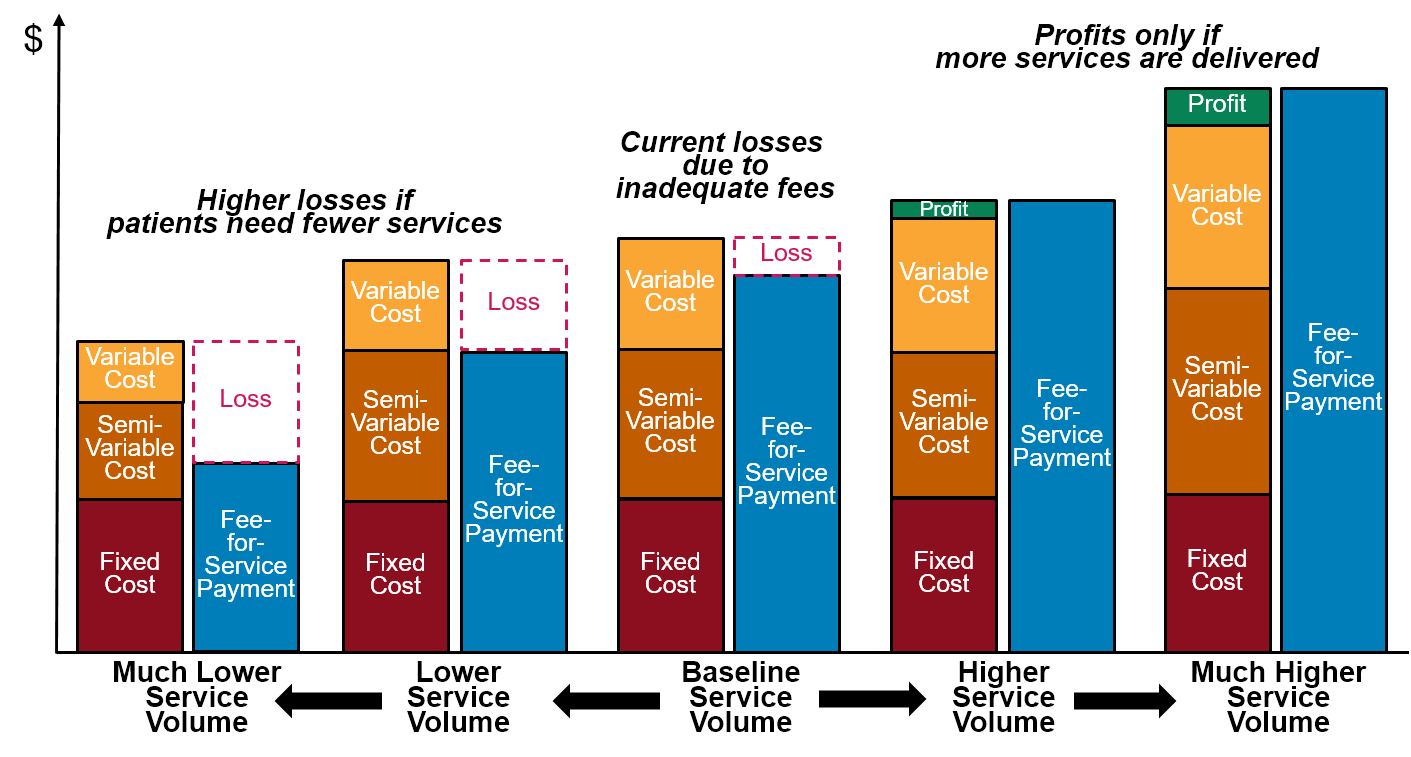

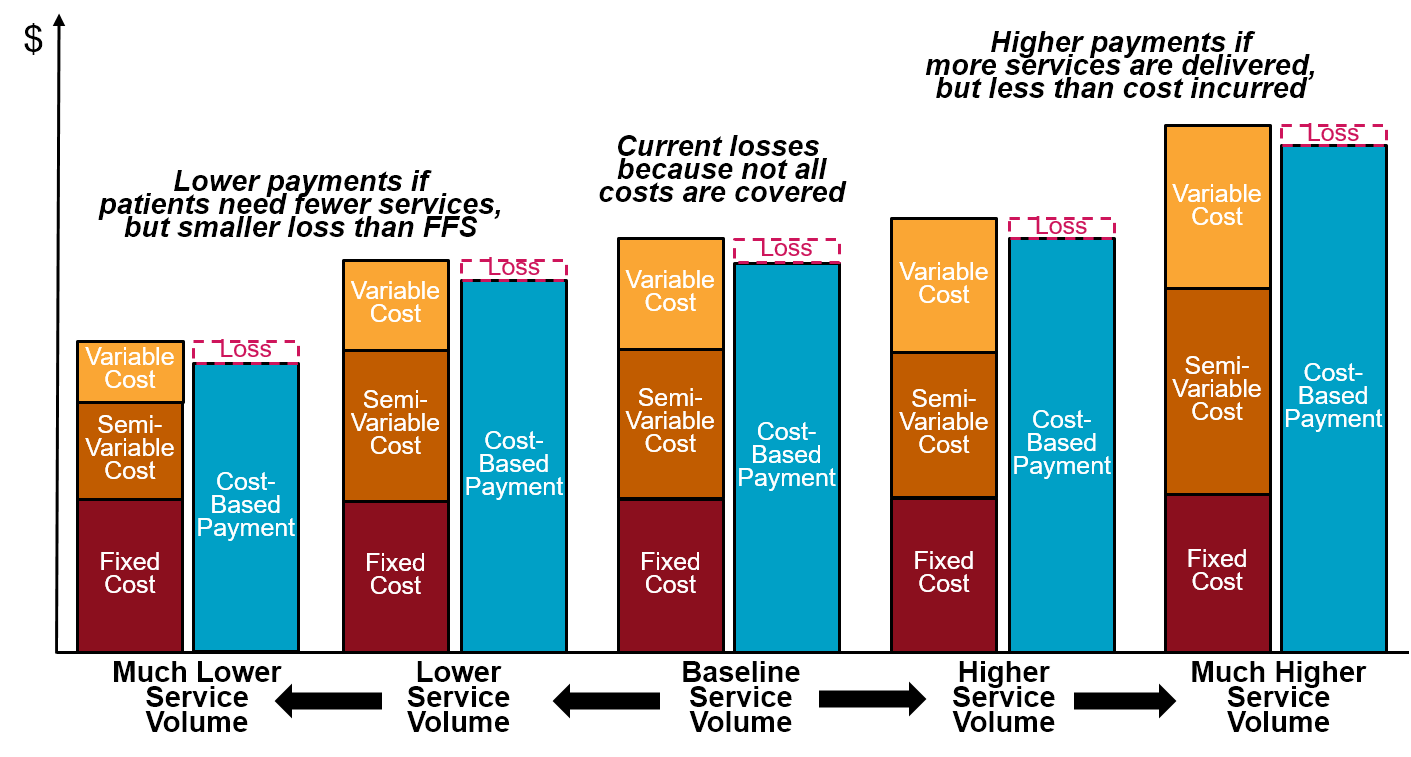

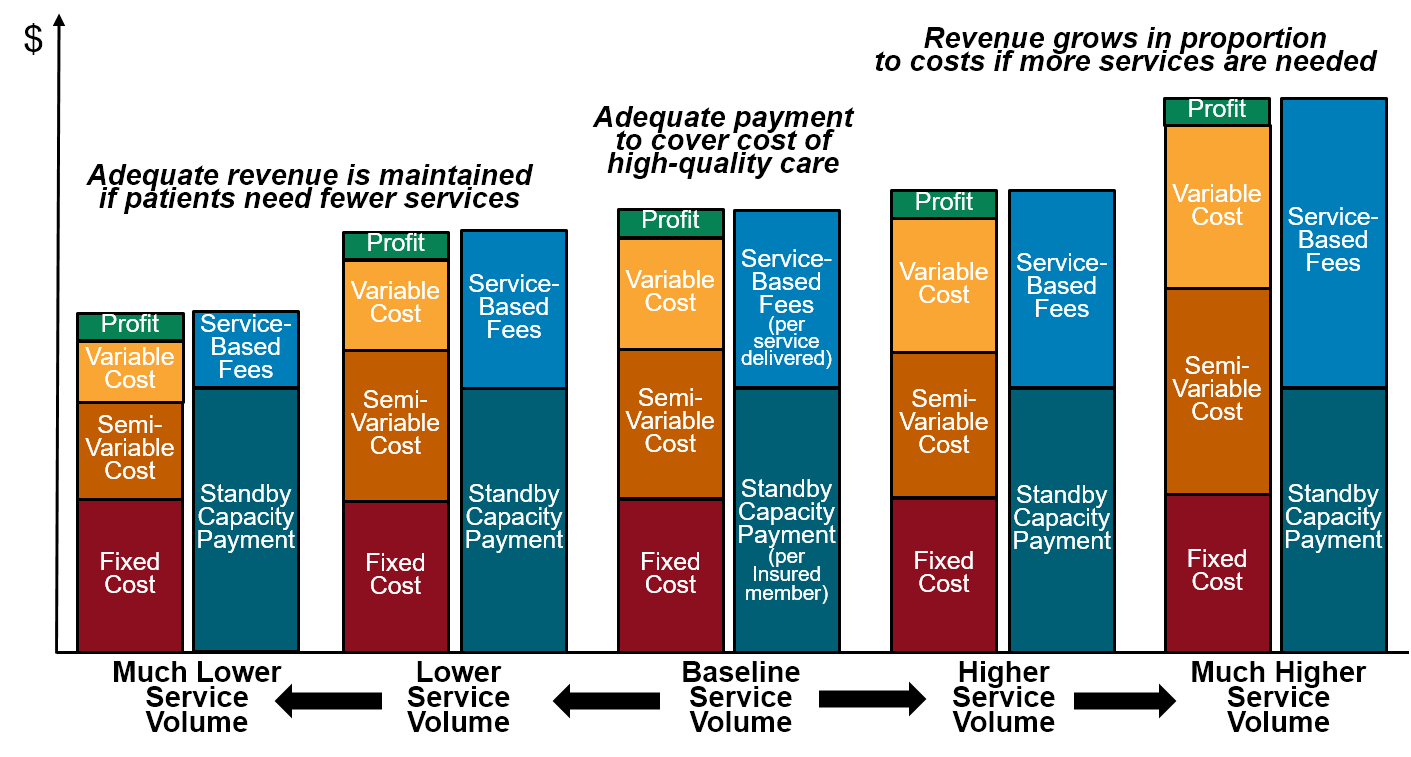

Current fee-for-service, cost-based payment, and shared savings systems do not achieve all of these goals, and neither would a hospital global budget or global payment program. It is not sufficient to make changes that just address one or two of the goals. For example, increasing fee-for-service payment amounts could eliminate hospital deficits and ensure availability of essential services in the short run, but this would do nothing to eliminate the penalties created by fee-for-service payment when hospitals work to improve the health of their residents. Conversely, changing the method of payment, without increasing the amount of payment sufficiently to cover the minimum costs of delivering services, will not prevent hospitals from closing. Incentives to improve the quality of services mean nothing if there are no services left to improve.

Figure 4

Effectiveness of Alternative Approaches to Rural Hospital Payment

| GOAL | EFFECTIVENESS IN ACHIEVING GOALS | |||||

| Fee for Service | Cost-Based Payment | Global Budget | Shared Savings |

Patient- Centered Payment |

||

| Ensure Availability of Essential Services in the Community | Ineffective | Effective | Mixed | Ineffective | Effective | |

| Enable Timely Delivery of Services Patients Need | Mixed | Effective | Harmful | Ineffective | Effective | |

|

Support Delivery of Appropriate, High-Quality, Affordable Care |

Appropriateness | Mixed | Limited | Mixed | Mixed | Effective |

| Safety/Quality | Mixed | Mixed | Harmful | Harmful | Effective | |

| Efficiency | Mixed | Harmful | Mixed | Limited | Effective | |

Patient-Centered Payment is needed to advance all three of these goals. An effective Patient-Centered Payment system for rural hospitals has four components, all of which are essential to success:

- Standby Capacity Payments to support the fixed costs of essential services.

- Service-Based Fees for diagnostic and treatment services based on variable costs.

- Accountability for quality and spending.

- Value-based cost-sharing for patients.

Under a Patient-Centered Payment System, separate payments for standby capacity and individual services match the way that costs change when patients need more or fewer services. As a result, Patient-Centered Payment is the only payment system that:

- Provides adequate payment to sustain essential services even if patients are healthier and need fewer services;

- Does not encourage stinting on necessary care; and

- Does not encourage delivery of unnecessary care.

Figure 5

Impact of Changes in Volume on Rural Hospital Margins

Under Alternative Payment Systems:

FEE FOR SERVICE PAYMENT

COST-BASED PAYMENT

HOSPITAL GLOBAL BUDGET

SHARED SAVINGS/RISK

PATIENT-CENTERED PAYMENT

The Cost of the Solution

It is impossible to prevent rural hospital closures without spending more money on small rural hospitals. The majority of small rural hospitals, no matter efficiently they are operated, are not receiving payments that are large enough to pay for the minimum costs of delivering those services. A “value-based payment” system will not help rural residents to receive high-quality care unless the payments are adequate to cover the cost of delivering that care. The goal of value-based payment should be to pay adequately but not excessively to enable delivery of high-quality care to patients, not simply to create savings for payers.

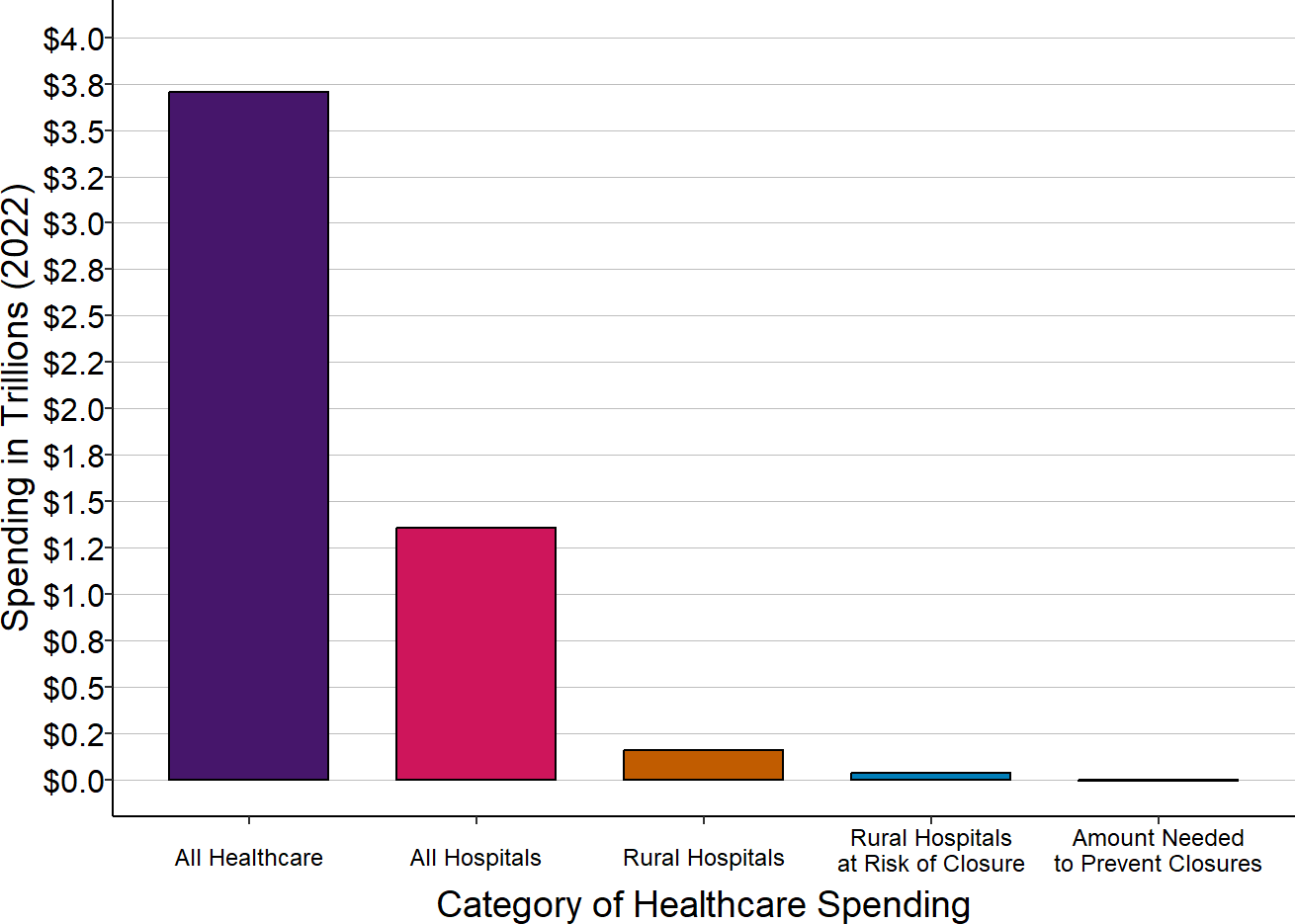

Although there are hundreds of rural hospitals at risk of closure, the total amount of money needed to prevent them from closing is relatively small because most of the hospitals are small. Half of the hospitals in the country are rural, but the total spending for services at those hospitals represents only 12% of the $1.5 trillion spent nationally on hospitals each year and less than 5% of the more than $4 trillion the country spends annually on all healthcare services. The increase in payments needed to eliminate the deficits at the at-risk rural hospitals would only increase national healthcare spending by a fraction of a percent. Specifically:

- Eliminating the losses for the rural hospitals at immediate risk of closing would cost approximately $2.2 billion per year.

- Eliminating the losses for all of the rural hospitals that are at risk of closing would cost approximately $3.2 billion per year.

The $6 billion in funding needed to prevent the closures would represent an increase of only one-tenth of one percent in the $4 trillion the nation spends on health care each year. This small increase in spending is also only 1/50 of the more than 4% average increase in healthcare spending that occurs every year. A large portion of the annual increase in spending nationally is caused by excessive prices and the delivery of unnecessary services; that portion of additional spending neither preserves access to care for patients nor improves the quality of care they receive. If high prices and unnecessary services can be reduced, a portion of the savings should be redirected to preserving access to rural healthcare services.

Figure 6

Spending Needed to Eliminate Deficits

at Rural Hospitals

Compared to National Healthcare Spending

Amount needed to prevent closures is the average annual loss, in the most recent three years for which data were available (other than 2020), for hospitals classified as being at risk of closure. National spending on all healthcare services is for 2023. Spending at rural hospitals is for the most recent year available (2024).

It is likely that most of the additional funding, if it were made available, would be used to support delivery of primary care and emergency care services, not inpatient care or ancillary services. because low payments for emergency services and primary care services are the largest causes of losses at many small rural hospitals.

In contrast, if rural hospitals close because they are not paid enough to cover the cost of delivering patient services, healthcare spending on the residents of those communities would likely increase anyway, because reduced local access to preventive care and prompt treatment will cause the residents to need even more services and more expensive services than they would otherwise.

Achieving Multi-Payer Payment Reform for Rural Hospitals

A rural hospital should provide access to high-quality services to all residents of the community, not just a subset of them. The hospital cannot do this if only one or two payers change the way they pay for services. Every payer – every commercial insurance plan, every Medicare Advantage plan, every Medicaid Managed Care Organization, every state Medicaid agency, and Original (fee-for-service) Medicare – needs to pay rural hospitals both adequately and appropriately. The best way to do that is by using Patient-Centered Payment.

In order for small rural hospitals to be paid adequately and appropriately by all payers, actions will need to be taken by a broad range of stakeholders, including the residents and employers in rural communities as well as health insurance companies, state governments, and the federal government.

Changing Payments from Private Insurance Plans

The payers who most need to change the way they pay small rural hospitals are private health insurance companies. The biggest cause of negative margins in most small rural hospitals in most states is low payments from private insurance plans, including both commercial insurance plans and Medicare Advantage Plans. Even in states where Medicaid payments for services are lower than private insurance payments, most rural hospitals have far more privately-insured patients than patients on Medicaid, so a shortfall in private payments has a much bigger impact on the hospital’s total margin.

Moreover, if payments from private insurance plans are high enough to not only cover the costs of services to privately insured patients, but to give the hospital a small positive margin on those services, that margin would also offset the losses the hospitals experience due to bad debt. For the smallest rural hospitals, a median profit margin on private-pay patients of only 6% would be sufficient to eliminate losses on bad debt. Under Patient-Centered Payment, Standby Capacity Payments would be set based on the number of residents of the community who have insurance, so that the aggregate revenues from those payments are sufficient to cover the costs of services to both insured and uninsured residents.

Why Private Health Plans Are Unlikely to Change on Their Own

Despite the importance of having private insurance companies change the way they pay rural hospitals, it is unlikely that most of them will do so without significant pressure from businesses, citizens, and government. There are several reasons for this:

- Paying rural hospitals more than they receive today will increase a plan’s “medical loss” and reduce the insurance company’s profit.4 Although the percentage increase in a plan’s total spending will likely be very small because rural hospitals represent such a small proportion of total healthcare spending, even a small increase in the amount the plan spends on healthcare services translates into a very large reduction in the amount of profits the insurance company can retain.5

- Making changes in contracts with hospitals, in benefit designs for patients, and in the internal systems used to make payments will increase the insurance company’s administrative costs, which will also reduce its profits. Even though the cost of changing to Patient-Centered Payment will be relatively small because it can be implemented easily within an existing claims payment system, any increase at all in the plan’s administrative costs will translate into a reduction in profits for the insurance company. This is also true for insurance companies that are simply processing claims for self-insured businesses; even if the business is willing to pay the hospital more or differently, it needs a health insurance company or third-party administrator (TPA) that is willing to implement the changes.

- Even though failure to sustain the rural hospital may increase health care costs in the community in the future, an insurance company can address that by increasing its premiums. In fact, the insurance company will want to charge higher premiums in the future in order to maintain or increase its profits, since profits and administrative costs are limited to a maximum percentage of total premium revenues.

What Communities Can Do to Encourage Changes in Private Health Plan Payments

There are several ways that private health insurance companies can be encouraged to implement the payment reforms that small rural hospitals need:

- Employers and community residents should only choose a health insurance plan that pays their rural hospital adequately and appropriately. Employers and citizens in rural communities likely have no idea that the insurance plan they are using may be helping to force their local hospital out of business. It does them little good to have an insurance plan with low premiums and/or low copayments if there is no longer a hospital or clinic in the community where they can use that insurance. Moreover, their premiums could increase even more in the future if healthcare spending increases because there is no longer a local source for preventive care and early treatment. However, there is only an incentive for an insurance plan to pay differently if it believes that doing so would increase its membership or that failure to do so would cause it to lose a large number of customers. The decisions made by the largest employers in the community about which health insurance plans to use will have the biggest impact on those plans’ willingness to change, simply because of the larger number of plan members who will be affected. In the short run, employers and citizens can focus on ensuring the health plan pays adequate amounts for services, while indicating that health plans will need to implement Patient-Centered Payment in future years in order to continue selling insurance in the community.

- Public and private employers in rural communities, including hospitals, should work together through purchaser coalitions to choose health insurance plans that pay adequately and appropriately. Most employers in rural communities are small businesses that individually represent only a small number of potential members for any health insurance company. By acting collectively, however, the employers can have much a greater impact on what a health insurance company will be willing to do. The employers can accomplish this by forming a healthcare purchasing coalition and either using information assembled through the coalition to make similar decisions about which plans to purchase, or by having the coalition purchase insurance collectively on their behalf. This is particularly important in regions where there is one dominant private insurance company, since other insurance companies are only likely to enter the market if there is a critical mass of purchasers who are willing to change the insurance plan they use.

- “Employers” includes local governments and school districts, not just private businesses. In most communities, they are larger than the majority of private businesses.

- Many businesses in the community will be part of national or multi-state firms, and the local manager does not make the decisions about which health insurance plan is used. These large firms can help their employees in rural areas by choosing health insurance carriers that pay rural hospitals adequately and appropriately.

- Hospitals are typically categorized as “providers” of healthcare, not “purchasers.” However, in most communities, the rural hospital is one of the largest employers in the community and so it is also one of the largest customers for a health insurance company in the community.6 The hospital is also in the best position to help other employers in the community determine whether the insurance plans they are using are paying adequately and appropriately for the hospital’s services. The biggest collective impact will likely be achieved if other employers in the community work together with the hospital to determine which health insurance plans will pay the local hospital adequately and appropriately while also providing the most affordable premiums overall. However, as discussed further below, hospitals must take steps to convince other employers that the hospital will use adequate health insurance payments to deliver high-quality care as efficiently as possible.

- A purchaser coalition does not need to be limited to one community. In states with many small rural hospitals, all of the hospitals will need to be paid differently by private health plans, and the same health plans are likely providing insurance in multiple communities, so a bigger impact can be achieved if the employers in several communities work together collectively.

- If a health plan is selling insurance to multiple employers in a region, it may also be more likely to sell insurance to individual community residents who purchase health insurance on an insurance exchange, so employers in the community could influence the individual insurance market as well as the group insurance market for their employees.

- Medicare beneficiaries should only choose a Medicare Advantage plan that pays their rural hospital adequately and appropriately. Medicare Advantage plans can be some of the most problematic payers for small rural hospitals. This is not only because they fail to pay adequately or appropriately for services at all rural hospitals, but at Critical Access Hospitals, they also reduce the proportion of services that are eligible for cost-based payment from Medicare. However, a small rural hospital can only be underpaid by a Medicare Advantage Plan if a Medicare beneficiary who lives in the community has chosen to enroll in that plan. Medicare beneficiaries in rural communities are unlikely to know that the plans they choose because of low premiums and other benefits are helping to force their local hospital out of business. In many cases, seniors may be more likely to preserve access to local healthcare services by staying on Original Medicare rather than enrolling in a Medicare Advantage plan. The beneficiaries need information and education from the rural hospital in order to make the right choices about their Medicare coverage.

- When there are health plan choices available to residents of the community, rural hospitals should refuse to contract with the plans that have the most problematic payment systems. A rural hospital can encourage health insurance companies to change by refusing to contract with a particular health plan if it fails to pay adequately and appropriately for the rural hospital’s services. However, this can harm local residents if they have few choices of health plans. If the hospital is not “in network” for the available health plans, the residents may have to pay higher cost-sharing amounts to receive services and that would make it more difficult for them to receive needed services and increase the hospital’s bad debt. If residents in the community do have a choice of health plans, then if the hospital contracts only with the plans that provide adequate and appropriate payment, it could help to accelerate use of those plans by employers and residents. This can best be done if hospitals work with employers on a coordinated effort to change the payment system.

- State insurance departments and state insurance exchanges should require health insurance plans to disclose the methods they use to pay rural hospitals and the amounts they pay, evaluate the adequacy of the payments, and encourage the plans to use Patient-Centered Payment for rural hospitals. State insurance departments and state insurance exchanges can help by requiring each health insurance plan to disclose the payment system it uses to pay small rural hospitals in the state and to demonstrate how the plan provides adequate, appropriate payments that achieve all three of the goals for rural hospital payment reform. This would enable consumers and purchasers to make more informed decisions about which insurance plans to use. In addition to requiring transparency about the methods of payment, the adequacy of payments could be assessed during reviews of the plans’ network adequacy and/or premium increase requests submitted by the plans. A state agency’s ability to do these things will depend on the extent of its regulatory powers and the extent of health insurance competition in rural communities, so some states will likely be able to do more than others.

Changes Needed in Medicaid

A state’s Medicaid program affects the financial viability of its rural hospitals in two different ways:

- Insurance Coverage. In states that have more restrictive Medicaid eligibility requirements, a larger number of low-income residents may have no health insurance and be unable to pay for the services they receive at the hospital. The more low-income individuals without insurance there are in a rural community, the greater the likelihood of financial losses at the community’s hospital.

- Payment for Services. For individuals who do have Medicaid coverage, the payments small rural hospitals receive from most state Medicaid programs are below the hospitals’ costs and are generally lower than what Medicare and private health plans pay. In these states, the more individuals who are on Medicaid in a rural community, the greater the likelihood of financial losses at the community’s hospital.

The Limited Benefit for Small Rural Hospitals From Expanding Medicaid Coverage

Many people have advocated for expanding Medicaid coverage as a way to help small rural hospitals. However, only a subset of the uninsured patients receiving services at rural hospitals in non-expansion states would likely qualify for Medicaid even if it were expanded. Moreover, in the states that have expanded Medicaid, Medicaid payments to rural hospitals have worsened, resulting in little net financial benefit to the hospitals.

Consequently, although expanding Medicaid coverage is desirable for many reasons, it is less likely to prevent rural hospital closures than improving the way the state Medicaid program pays rural hospitals. Moreover, if a small rural hospital receives Patient-Centered Payment from Medicaid and most other payers, the Standby Capacity Payments will enable it to provide essential services to uninsured patients.

The Difficulties of Improving Medicaid Payments for Rural Hospitals

In states where the state Medicaid agency directly pays healthcare providers for their services, the agency can simply decide to use a Patient-Centered Payment system for rural hospitals in the state and begin doing so.

However, in most state Medicaid programs, hospitals and clinics are now paid primarily by Medicaid Managed Care Organizations (MCOs). Medicaid MCOs are typically health insurance companies that the state Medicaid agency has contracted with to “manage” healthcare services for most or all Medicaid beneficiaries. The MCO receives a capitation payment from the state for each Medicaid beneficiary, and the MCO then pays hospitals and clinics for the services they deliver to those beneficiaries, typically using fees for individual services.

It will be much more difficult for a state Medicaid program to ensure adequate and appropriate payments for its rural hospitals if the state uses Medicaid MCOs, since each MCO will have to agree to change the way it makes payments. MCOs will be unlikely to do so voluntarily for the same reasons described earlier for commercial insurance plans. Paying a hospital or clinic more and changing the method used to pay them will reduce an MCO’s profit, whereas if the rural hospital closes and Medicaid beneficiaries receive fewer services as a result, the MCO’s profit will increase. If Medicaid beneficiaries’ health worsens, and that causes their need for healthcare services to increase in the future, the state will have to pay the MCOs more, since federal law requires that the MCO receive an “actuarily sound” payment from the state.7 These higher payments will also allow the MCOs’ profits to increase.

State Medicaid programs cannot simply require MCOs to change the way they pay rural hospitals, because regulations issued by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) limit states’ ability to specify how MCOs should pay healthcare providers or how much they should pay. Under the regulations, a state is only permitted to require that a Medicaid MCO implement a “value-based purchasing model” that is “intended to recognize value or outcomes over volume of services” or to require an MCO to participate in a “delivery system reform or performance improvement initiative.” Moreover, CMS requires that any payments the MCO is required to make must be “based on the utilization and delivery of services” and “advance at least one of the goals and objectives in the state’s quality strategy,” and participation must be available, using the same terms of performance, to a “class of providers” providing services related to the payment model. If a state wants to require such a payment model, it has to receive approval from CMS before it can do so, and the arrangement “cannot be renewed automatically.”8

A state Medicaid program is also prohibited from making payments directly to hospitals to address perceived shortfalls in their revenues. In the past, many states made “supplemental payments” to hospitals, but CMS regulations no longer permit them to do so for services that the MCOs pay for. The only exception is the “wrap-around payments” that federal law requires states to use in order to offset the low amounts that most MCOs pay to Rural Health Clinics for their services.9

Federal and State Actions Are Needed to Improve Medicaid Payments to Rural Hospitals

It will be very slow and inefficient if every state is forced to submit a separate request to CMS to require Medicaid MCOs to change the way they pay small rural hospitals, wait for CMS to review the request, make revisions in response to CMS questions, and then wait for final approval. In order for rural hospitals to get adequate and appropriate payments as quickly as possible, both the federal and state governments should take the following actions:

- CMS should establish a policy indicating that approval will be given to states that want to require MCOs to use Patient-Centered Payment to pay small rural hospitals, and CMS should quickly approve state proposals to do so. A properly-designed Patient-Centered Payment system clearly satisfies the requirements for a “value-based purchasing model” or “delivery system reform initiative” under CMS regulations. Because hospitals would still receive fees for individual services under Patient-Centered Payment, it meets the requirement that payments be based on the utilization and delivery of services (in contrast to a global budget model, which provides the same payment regardless of how many services are delivered). Because the payment amounts are designed to ensure delivery of essential services, and because payments are only made if services meet quality standards, Patient-Centered Payment satisfies CMS requirements that payments advance quality goals and recognize value over volume. If CMS does not believe that Patient-Centered Payment meets those regulatory requirements, it should change the regulations rather than force undesirable changes in the Patient-Centered Payment model that could harm hospitals.

- In states with small rural hospitals that use Medicaid MCOs, the state Medicaid agency should request approval from CMS to require MCOs to use Patient-Centered Payments for rural hospitals that wish to be paid that way. The state Medicaid agency should work with the state’s rural hospitals to ensure the design of the program will provide adequate payment to support the hospital’s essential services and to ensure that MCOs are implementing the payments correctly. If purchaser coalitions in the state are working to encourage implementation of Patient-Centered Payment by private health plans, it would be desirable for the state to also participate as a purchaser in order to ensure a coordinated, multi-payer approach.

- In states with small rural hospitals that do not use Medicaid MCOs, the state Medicaid agency should begin using Patient-Centered Payment to pay rural hospitals. In these states, the Medicaid agency should work with the state’s rural hospitals to design the Patient-Centered Payment system and then the state should implement the payments with hospitals that wish to participate. If a purchaser coalition in the state is working to encourage implementation of Patient-Centered Payment by private health plans, it would be desirable for the state to work with the coalition to ensure a coordinated, multi-payer approach.

Changes Needed in Medicare

Medicare is Not the Primary Cause of Financial Problems at Most Small Rural Hospitals

For most small rural hospitals, the Medicare program is currently their “best” payer, in the sense that the losses on Medicare patients are smaller than the losses on patients with other types of insurance. This is because most small rural hospitals are classified as Critical Access Hospitals and thereby receive cost-based payment for the services they deliver to Medicare beneficiaries (except for beneficiaries who have enrolled in a Medicare Advantage plan). Medicare may or may not be the best payer for hospitals that do not qualify for Critical Access Hospital status; the majority of small rural hospitals that are not CAHs lose money on their Medicare patients. However, the losses on privately-insured patients at many of these hospitals are still larger.

Cost-based payment is problematic for many reasons, and the way Medicare has implemented it for Critical Access Hospitals is particularly problematic for the hospitals. Some people inappropriately refer to Medicare’s system as “cost-plus” payment, but there is no “plus” in the payments, only a minus. Due to federal sequestration requirements, Critical Access Hospitals currently can be paid at most 99% of their costs for services delivered to Medicare beneficiaries, even though no business could survive if it were only paid 99% of its costs. In addition, hospitals are only eligible for the program if they are more than a minimum mileage from other hospitals, regardless of the travel time that would be required for patients to reach the other hospitals or whether the other hospitals offer similar services with comparable quality, so some small rural hospitals that would be appropriate for the program cannot participate.

Changes in the current Medicare cost-based payment systems would certainly be desirable. For example, eliminating sequestration reductions and the productivity adjustment for Rural Health Clinics would reduce losses on Medicare patients for small rural hospitals, and requiring Medicare beneficiaries to pay no more for services at Critical Access Hospitals than they pay at larger hospitals would help both the patients and the hospitals. However, these changes alone would be unlikely to eliminate losses or prevent closures at most small rural hospitals.

Use of Patient-Centered Payment in Medicare is Desirable But Not Essential

A properly designed Patient-Centered Payment system would be beneficial for both Critical Access Hospitals and for small rural hospitals that do not qualify for designation as a Critical Access Hospital. Consequently, it would be desirable for Medicare to make Patient-Centered Payment available to all small rural hospitals. Moreover, because the payments used by Medicare often serve as a model for other payers, implementation of Patient-Centered Payment by Medicare could accelerate implementation of the system by other payers.

While it would be desirable for Medicare to implement Patient-Centered Payment, it is not essential for success. Increasing Medicare payments alone would only eliminate financial losses at about 2% of small rural hospitals. If private health plans and Medicaid programs paid adequately but Medicare made no changes at all, most of the small rural hospitals that are experiencing financial problems would likely be able to remain open. Conversely, there will be little benefit for small rural hospitals if only Medicare changes the way it pays small rural hospitals while private health plans and Medicaid do not.

CMMI Demonstrations Could Harm Rural Hospitals

A corollary is that it would be better for Medicare to do nothing than to make changes in payments that would be worse for small rural hospitals or that would cause other payers to delay action in implementing Patient-Centered Payment. For several years, the CMS Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) has been actively encouraging states to replicate the Pennsylvania Rural Health Model that was designed by CMMI, even though that program would be unlikely to help the smallest rural hospitals and would likely harm many of them. The CMMI CHART Model announced in August 2020 creates an approach to global budgets that is even less favorable than the approach that has been used in Pennsylvania. Moreover, because it will likely take 3-4 years before even a preliminary evaluation is completed and 7 or more years for a final evaluation to be completed, these demonstration projects could easily cause other states and private health plans to “wait to see the results” before doing anything to help the majority of rural hospitals in the country. If this happens, many small rural hospitals will likely be forced to close in the meantime.

It is unlikely that CMMI would ever implement a demonstration that would effectively address current inadequacies in payments for small rural hospitals or primary care clinics because CMMI is prohibited by law from testing payment models that would require higher spending by the Medicare program.10 Although CMMI is authorized to implement demonstrations that are not initially budget neutral, it cannot continue them unless they are expected to reduce Medicare spending. This is why the Pennsylvania Rural Health Model merely continues current payment amounts for rural hospitals rather than increasing them sufficiently to eliminate hospital deficits, and why the CHART Model explicitly requires reductions in payments to hospitals and provides no mechanism for increasing payments to erase current deficits. Any new program would have similar limitations unless Congress changes the enabling legislation for CMMI.

How Medicare Should Help Small Rural Hospitals

Medicare can and should be a leader in implementing Patient-Centered Payment for rural hospitals. To achieve that:

- Congress should create a Patient-Centered Payment program for Medicare beneficiaries in which any small rural hospital can voluntarily enroll. Hundreds of small rural hospitals need help, and they need it now. No small demonstration program can provide that help. Congress should use the same approach that it used when it created the Critical Access Hospital program, i.e., creating a better payment model in Medicare for small rural hospitals, and giving rural hospitals the option of whether to participate. Congress used a similar approach when it created the Medicare Shared Savings Program – it is a permanent program, not a temporary demonstration project, and participation by hospitals and physicians is voluntary, not mandatory. These programs were implemented as part of the regular Medicare program, not through CMMI.

Most of the payment systems Medicare currently uses to pay hospitals have been implemented without “testing” them first through CMMI or other means. In addition to the voluntary payment system created for Critical Access Hospitals:

- The Inpatient Prospective Payment System (i.e., hospital DRGs) was designed and implemented for most hospitals across the country in 1983 without any evaluation demonstrating that it would work.11 It was implemented nationwide just 14 months after Congress passed the authorizing legislation.

- The Outpatient Prospective Payment System was implemented in 2000 to pay hospitals for outpatient procedures, with no testing or evaluation prior to implementation.

Instead of being tested in an artificial demonstration, all of these payment systems were made available nationally in a phased but rapid approach. Since then, they have been monitored and regularly adjusted to correct any unanticipated problems and to adapt the payment systems as changes in medicine, technology, and other factors occurred over time.

Most recently, the Rural Emergency Hospital payment category was established by Congress in 2021, and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) issued regulations implementing this new payment method in 2022, with no testing or evaluation prior to implementation.

Congress could make Patient-Centered Payment available to rural hospitals in the same way.

What Rural Hospitals Need to Do

The Need for Transparency About Rural Hospital Costs and Efficiency

In order to be successful for patients and payers as well as for hospitals, the payment system for rural hospitals needs to achieve all three of the goals defined earlier, not just one or two of them:

- In order to ensure availability of essential services in the community and to enable safe and timely delivery of services to patients, the payments made to rural hospitals need to be large enough to cover the minimum costs they will incur in delivering high-quality care.

- In order to enable patients to receive services at prices they can afford to pay and to encourage lower healthcare spending, the payments must be no larger than necessary to cover the lowest costs a rural hospital can feasibly achieve while delivering high-quality care.

Rural hospitals are in the best position to define what payment amounts are large enough, but no larger than necessary, to achieve all of these goals. This requires not only that they understand what it costs to deliver essential services, but also that they pursue every feasible opportunity to reduce their costs without harming patients.

The average cost per service even in the most efficiently operated small rural hospital will be higher than in larger hospitals, and the cost will be even higher for some small hospitals than others for many reasons that are beyond the control of the hospitals. However, it is impossible to determine from the cost data that hospitals currently report whether individual hospitals have higher-than-average costs for reasons they can or cannot control.

In order for purchasers and payers to be willing to pay adequately to support rural hospitals’ services, they will need to have confidence that the payment amounts recommended by rural hospitals are, in fact, no larger than necessary to deliver high-quality care to patients, and that any differences in payments between hospitals are necessary to address factors beyond the control of the hospital, not to subsidize inefficiencies. The data to demonstrate this will need to come from hospitals.

Unfortunately, most purchasers and payers are unlikely to have confidence in payment amounts recommended by hospitals, at least initially, because so many hospitals across the country have been secretive about their costs and have engaged in problematic activities designed primarily to maximize profits rather than control costs. For example, a number of studies have shown extremely large variations among hospitals in charges and payments for individual services and utilization of services that cannot be justified based on patient needs or differences in unit costs.12

To address this:

- Small rural hospitals that want to receive adequate, appropriate payments should work together to objectively estimate the minimum feasible costs for delivering essential services and publicly release the methodology used to make the estimates. The methodology to estimate costs of essential services at rural hospitals described in The Cost of Rural Hospital Services can serve as a starting point for this. Rural hospitals can build in greater detail to reflect the impacts of different staffing plans, equipment costs, etc.

- Individual hospitals should be transparent about how and why their own costs differ from the estimated minimum costs of delivering services. For example, a hospital could show how the loss of a physician or other clinician in the ED or clinic resulted in higher costs to use a locum tenens physician and to recruit a permanent placement.

- Hospitals need to provide information showing how much they are currently paid for services by each payer compared to the cost of delivering those services. It is currently impossible to determine exactly which services are losing money at small rural hospitals and which payers are underpaying them for their services. It will be difficult to get payers to pay more or differently unless there is clear evidence that they are underpaying for services today.

- Small rural hospitals that want to receive adequate, appropriate payments should proactively pursue efforts to improve their efficiency and provide evidence demonstrating they are achieving success. For example, if rural hospitals generate comparable information about the costs of operating various service lines, and compare their own costs to those of other hospitals, many hospitals will likely identify cost-reduction approaches used by other hospitals that could be adapted to their own facility.

- Small rural hospitals will need funding and technical assistance programs to carry out these tasks and to implement new payment systems. The federal government spends significant amounts of money every year to support research on rural hospital issues and to provide technical assistance to rural hospitals. A significant portion of this funding needs to be devoted to generating the information on costs of service delivery and causes of losses at rural hospitals that will support development and implementation of improved payment systems.

The Need for Transparency about the Quality of Care and Quality Improvement at Rural Hospitals

In addition, many purchasers and payers will likely resist paying more to small rural hospitals and clinics without assurance that the hospitals/clinics are delivering high-quality care and taking active steps to improve care wherever feasible. Most of the quality measures typically used by Medicare and other payers to assess the quality of care in hospitals are inaccurate or inappropriate for use with small rural hospitals, but most rural hospitals do not provide patients or purchasers with any alternative information demonstrating that they deliver high quality care. This can cause both purchasers and patients to believe that the quality of care in small rural hospitals is poor or that the hospitals are not concerned about quality.

To address this:

- Small rural hospitals that want to receive adequate, appropriate payments should publicly report on the quality of their care using quality measures that can be included in the accountability component of the payment model. Hospital quality measures such as ED response time, medication safety, etc. can be collected and reported by every small rural hospital, and the clinic quality measures can be collected and reported by any hospital that operates a Rural Health Clinic. Collecting and reporting these measures now will not only demonstrate that the hospital currently delivers high-quality care, but help prepare it to take accountability for success on those measures as part of a Patient-Centered Payment system. Many small rural hospitals are already collecting these measures through the Medicare Beneficiary Quality Improvement Program (MBQIP)13, so they simply need to release the results publicly.

- Small rural hospitals should work with purchasers and payers to identify potential opportunities for reducing avoidable healthcare spending that the hospitals could implement once a Patient-Centered Payment system is in place. It will be much easier to demonstrate to purchasers and payers that Patient-Centered Payment will help to control spending and improve outcomes if they see concrete examples of how hospitals would change care delivery in ways that would improve quality and reduce spending.

Footnotes

Some hospitals had a positive margin in one year, but the losses in the other years were large enough to offset that. At small hospitals, margins can be artificially high or low in one year because of variability and uncertainty about payment, so calculating the margin over a 2-year period is a more robust measure of profitability.↩︎

Both the hospital’s current net assets (the difference between current assets and current liabilities) and total net assets (the difference between total assets other than buildings and equipment and long-term liabilities) were examined to determine how long the hospital could potentially sustain losses. In addition, it was assumed that federal aid that the hospital received during the pandemic (other than advance Medicare payments that had to be repaid) was available to cover losses.↩︎

The Medicare Program already pays more to small rural hospitals than it does to larger hospitals. Most small rural hospitals are classified as Critical Access Hospitals and are eligible for cost-based payment for both inpatient and outpatient services. However, due to federal sequestration, the cost-based payments are only 99% of costs. For rural hospitals not classified as Critical Access Hospitals, the Medicare Low-Volume Hospital Payment Adjustment increases payments under the Inpatient Prospective Payment System if the hospitals have less than 3,800 discharges per year. The maximum increase is 25% for hospitals that have 500 or fewer discharges (which is equivalent to an average daily acute census of about 3-4 patients), and the adjustment decreases linearly for hospitals with more discharges, with no adjustment at all for hospitals that have more than 3,800 discharges (equivalent to an average daily census of about 26 patients). However, as shown in , the average cost per day at hospitals with an average census of 3 is twice the average cost at hospitals with 10 or more patients, and the cost for hospitals with fewer patients is even higher, so a 25% increase in payments per admission at the smallest hospitals will not eliminate the difference between payments and costs for inpatient care.↩︎

Even though the standby capacity payments and service fees based on marginal costs would reduce variation in spending and potentially reduce avoidable utilization, the fact that payments are already so low would still likely result in higher spending in the short run for the health insurance plan.↩︎

For example, if 80% of premium revenues are used to pay medical expenses, 15% are used to pay administrative costs, and 5% represents profit for the insurance company, then a 1% increase in the total amount of medical expenses translates into a 20% reduction in the amount of profit the insurance company can retain.↩︎

Even if the rural hospital is self-insured, it will still be using a health insurance company or other Third Party Administrator (TPA) to process claims for services its employees receive from other hospitals and healthcare providers.↩︎

Actuarial Soundness. 42 CFR §438.↩︎

Special Contract Provisions Related to Payment. 42 CFR §438.6↩︎

Wachino V. Letter to State Health Officials Re: FQHC and RHC Supplemental Payment Requirements and FQHC, RHC, and FBC Network Sufficiency Under Medicaid and CHIP Managed Care, April 26, 2016. Center for Medicaid and CHIP Services.↩︎

Section 1115A of the Social Security Act created the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation to “test innovative payment and service delivery models to reduce … expenditures … while preserving or enhancing the quality of care.” 42 U.S.C. 1315a.↩︎

Although the Health Care Financing Administration (the predecessor to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services) sponsored a demonstration project in New Jersey to pay hospitals under a DRG system, the demonstration was not completed or evaluated before the Inpatient Prospective Payment System was implemented nationally and the DRG system used in New Jersey was significantly different from the system Medicare implemented nationally. Hsiao WC et al. Lessons of the New Jersey DRG Payment System. Health Affairs 5(2):32-45 (1986). Smith DG. Paying for Medicare: The Politics of Reform. New York: Aldine de Gruyter (1992).↩︎

White C, Whaley C. Prices Paid to Hospitals by Private Health Plans Are High Relative to Medicare and Vary Widely: Findings from an Employer-Led Transparency Initiative. RAND Corporation (2019). Available at: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR3033.html

Health Care Cost Institute. 2018 Health Care Cost and Utilization Report. February 2020. https://healthcostinstitute.org/annual-reports/2020-02-13-18-20-19↩︎U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration. Medicare Beneficiary Quality Improvement Project. https://www.hrsa.gov/rural-health/rural-hospitals/mbqip↩︎