Cost of Rural Hospital Services

Most spending at small rural hospitals is for delivery of six essential services: (1) the Emergency Department, (2) inpatient services, (3) the laboratory, (4) radiology, (5) drugs and medical supplies, and at most hospitals, (6) one or more Rural Health Clinics.

The cost of an Emergency Department visit is inherently higher at small rural hospitals than at larger hospitals. At least one physician needs to be available around the clock in order to respond to injuries and medical emergencies quickly and effectively, regardless of how many patients actually visit the ED. Since this “standby capacity” cost will not decrease even if fewer patients visit the ED, the average cost per ED visit will be higher in a smaller community.

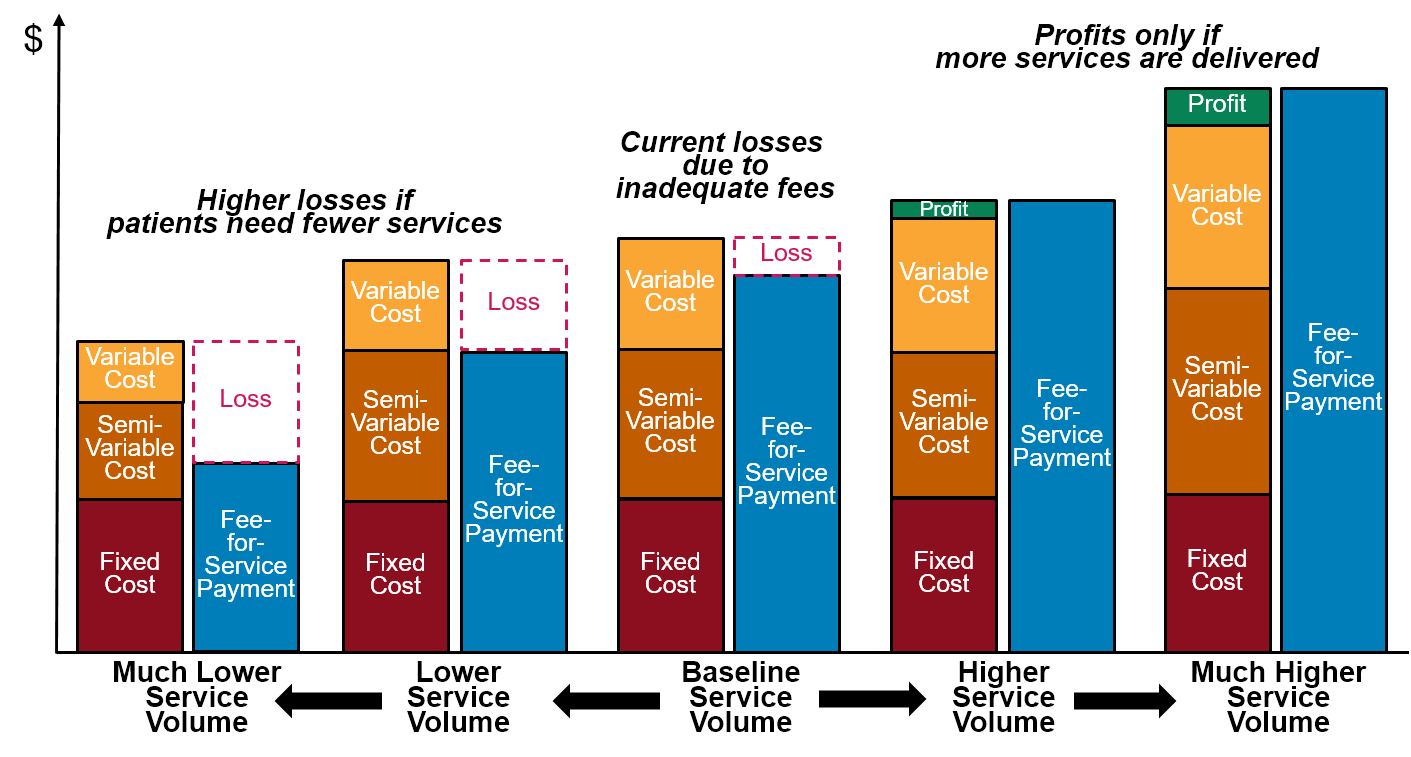

The cost of inpatient care, laboratory tests, imaging studies, primary care visits, and most other essential services is also inherently higher at small rural hospitals. For almost every type of service the hospital delivers, there is a minimum level of staffing and equipment required to deliver the service. As a result, the average cost per service will be higher in a smaller community where fewer services are needed.

Use of fee-for-service payments increases the likelihood of financial losses at small rural hospitals. Under the fee-for-service payment systems used by most health plans, the hospital receives the same fee for delivering a service regardless of how many times the hospital delivers that service. When fewer services are delivered, fee-for-service revenues decrease, even though the costs at a small rural hospital will not decrease. As a result, a hospital will be financially penalized if it helps the residents of its community stay healthy and they need fewer services.

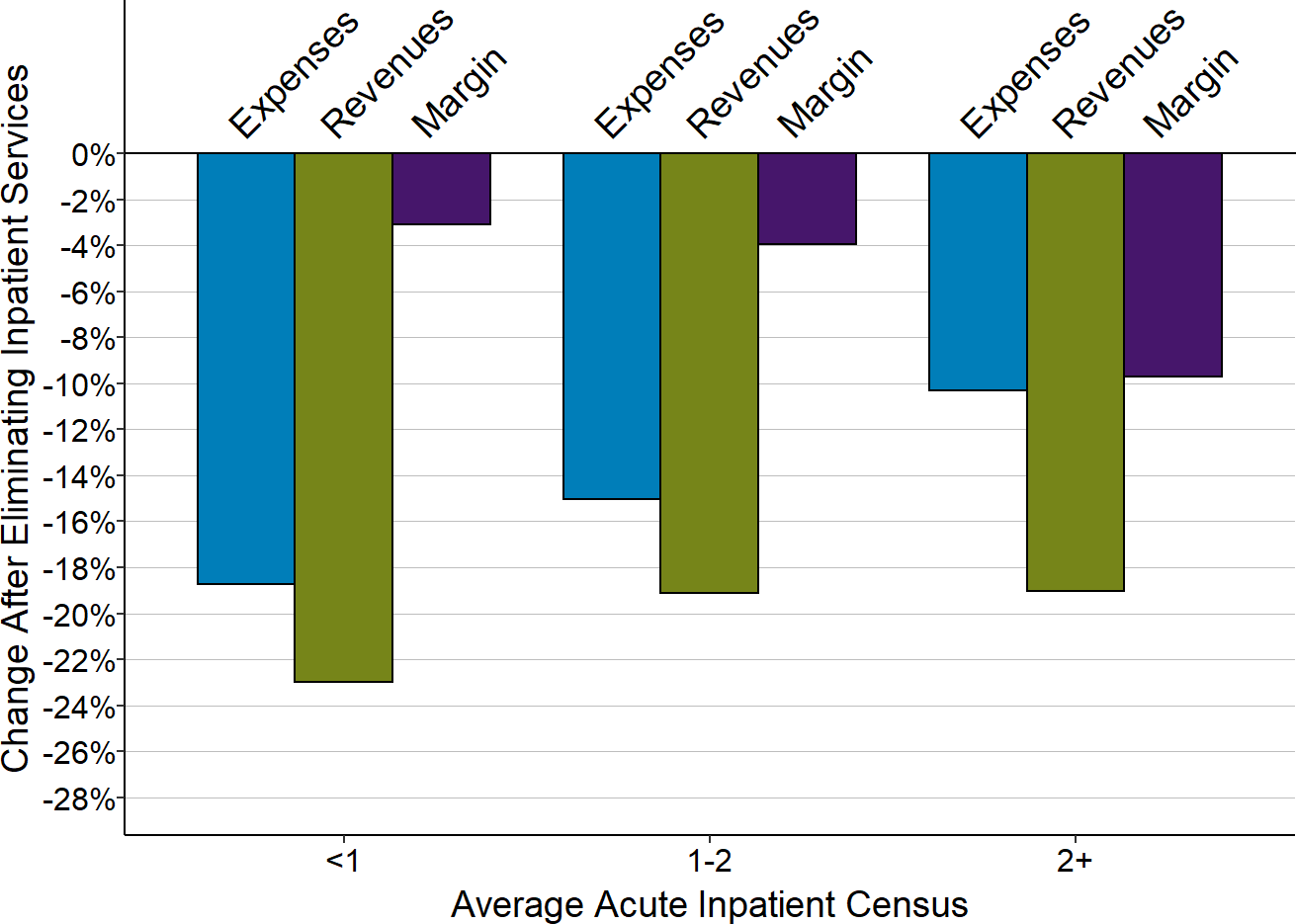

Eliminating inpatient care would harm both the hospitals and their communities rather than preventing closures. In most cases, the revenues generated by inpatient care at a small rural hospital exceed the direct costs of delivering that care, so the hospital would be worse off financially if it no longer received those revenues. Moreover, the smallest rural hospitals have many patients receiving inpatient rehabilitation and/or long-term nursing care in their inpatient beds in addition to individuals receiving acute inpatient care. Closure of the inpatient unit would deprive the residents in the community of all of these services, as well as limit the ability of the hospital to respond to a pandemic or other health emergency.

The Major Categories of Expenses in Small Rural Hospitals

Direct Service Costs vs. Overhead Costs

Most hospital expenses fall into two major categories:

- Direct Service Costs. These are the costs associated with personnel who provide the services individual patients receive, such as the nurses in the inpatient unit, the physicians and nurses in the emergency department, and the technicians in the laboratory, as well as the costs of the equipment and supplies these personnel use to deliver services to patients.

- Overhead Costs. These are the costs associated with personnel who do not provide services directly to or for patients, such as the hospital’s accounting and billing departments, the human resources department, medical records, information systems, and maintenance.This also includes the costs of building and maintaining the hospital’s facilities.

A third and much smaller category consists of the direct costs of non-patient service activities, such as a gift shop, parking lot, or housing for staff.

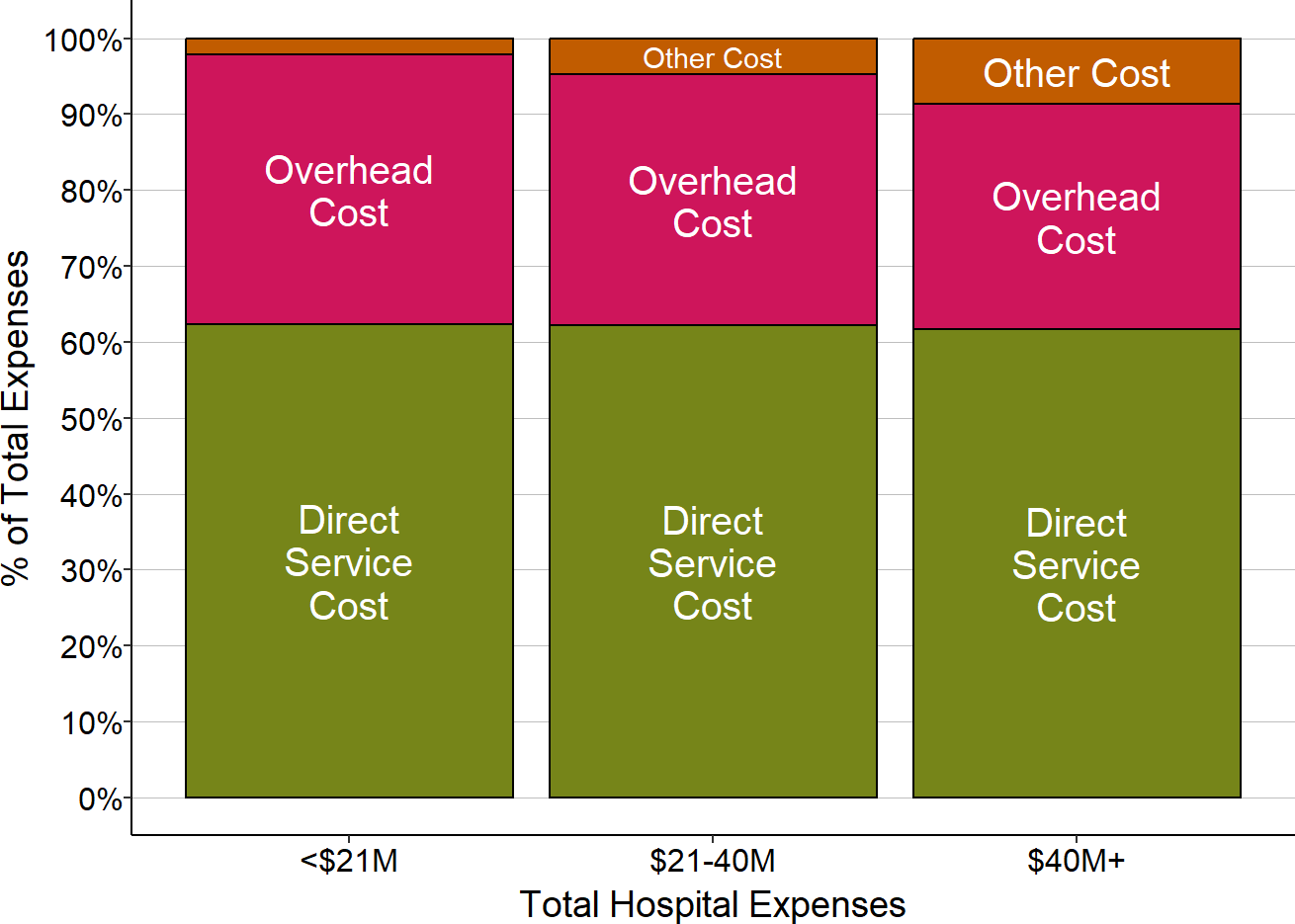

About 60% of the total expenses of small rural hospitals consists of direct service costs, and about 35% consists of overhead costs. Non-patient service activities represent less than 5% of total expenses at most hospitals.

Figure 1

Spending on Direct Services vs. Overhead Costs

in Small Rural Hospitals

Medians for most recent three years available. “Other” = costs associated with non-patient service activities.

The Largest Categories of Direct Service Costs

A core group of six services constitute the majority of direct patient service costs at small rural hospitals:

- the Emergency Department,

- inpatient services,

- the laboratory,

- radiology,

- drugs and medical supplies, and

- the Rural Health Clinic (if the hospital operates an RHC).

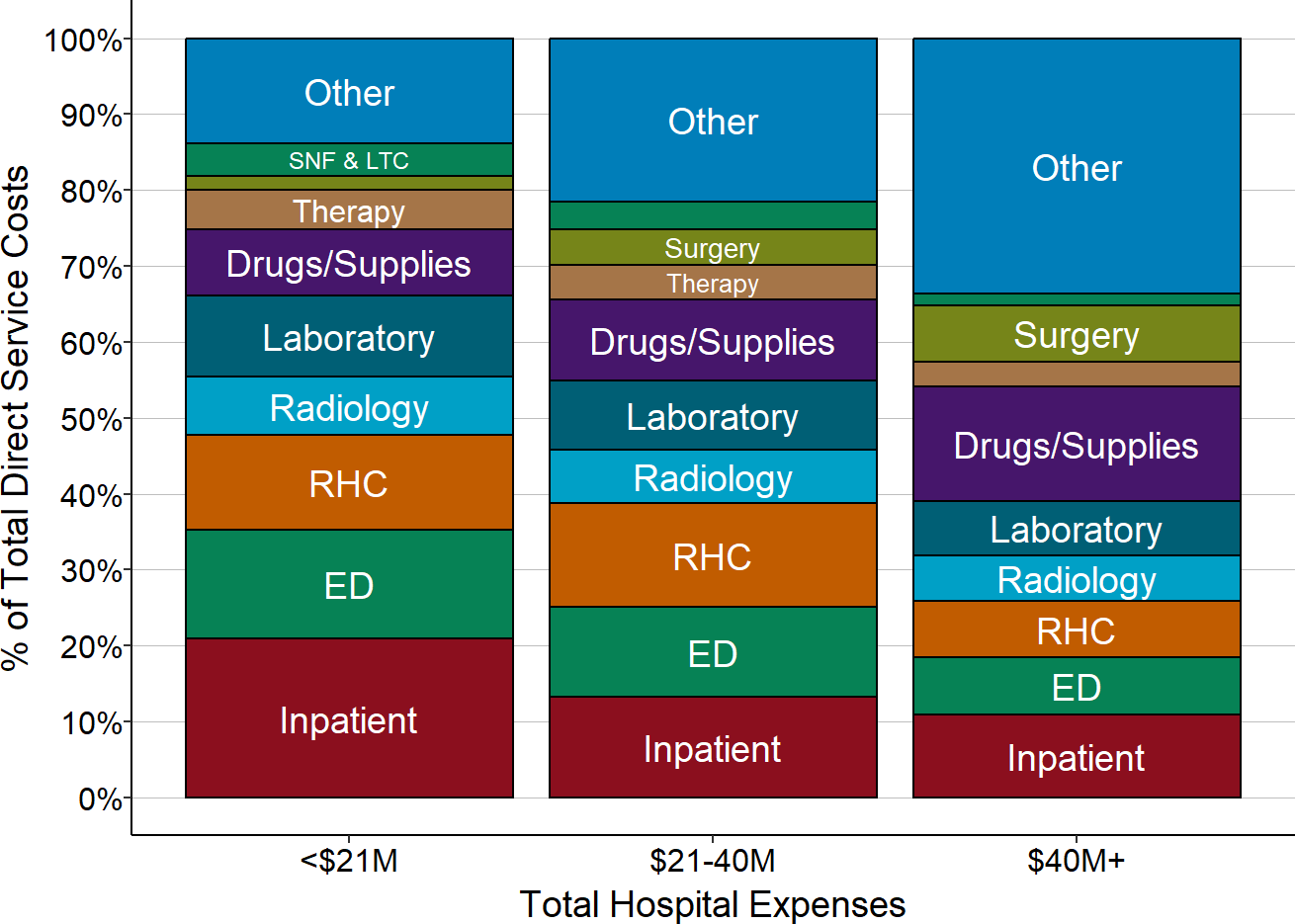

At small rural hospitals, these six core services represent over 60% of the hospital’s total direct patient service costs. Larger hospitals are more likely to offer other services, such as surgery and maternity care and to have larger numbers of patients receiving those services, so a smaller share of total costs at larger hospitals will be associated with the six core services, but the core services still represent more than half of direct patient service costs.

Figure 2

Direct Patient Service Costs in Rural Hospitals

Medians for most recent three years available.

Categories of Overhead Costs

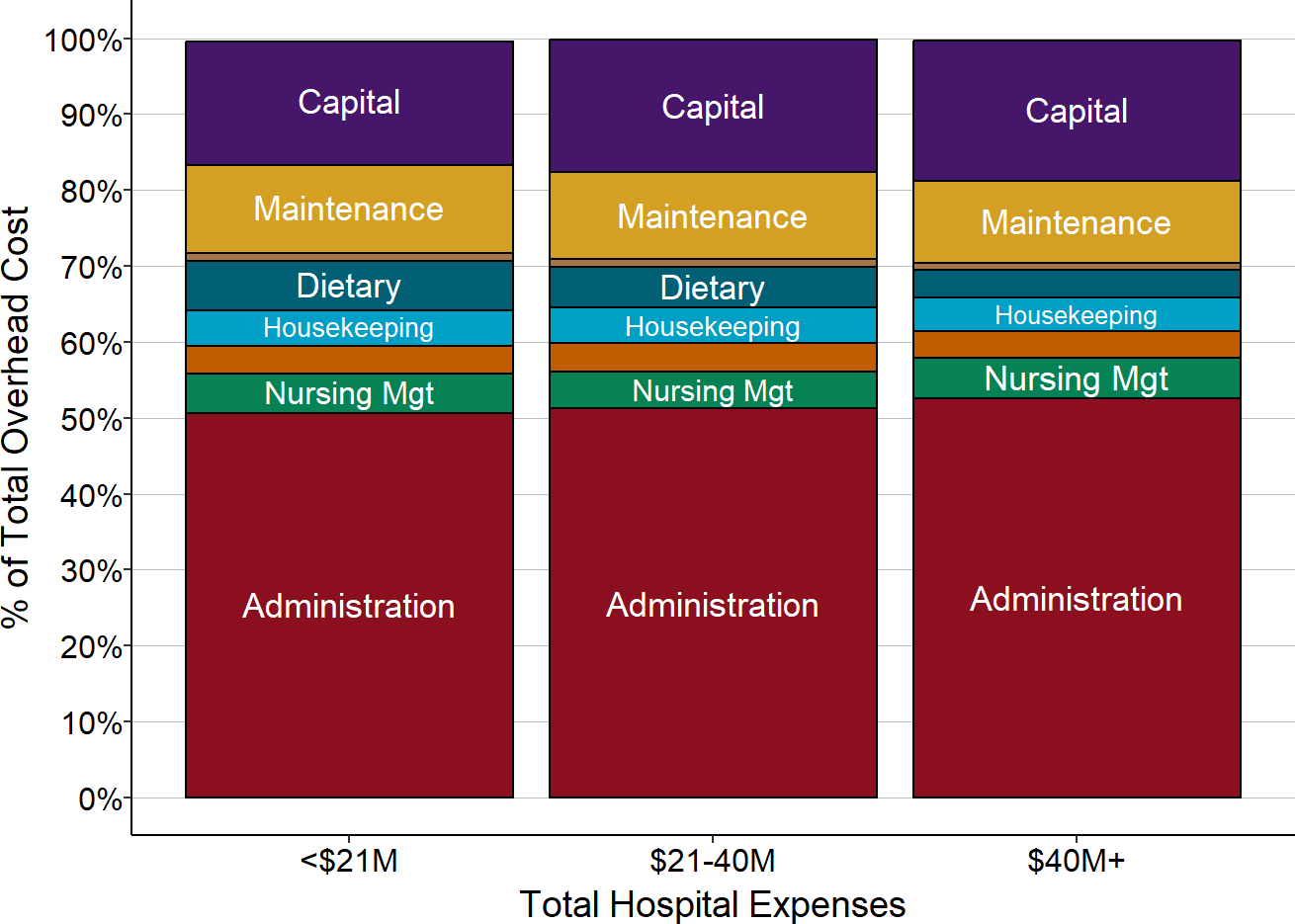

About half of overhead costs are for general administration of the hospital. This encompasses a broad range of activities, including accounting, human resources, billing, information systems, etc. Many small rural hospitals have had to spend large amounts of money to purchase and maintain an Electronic Health Record (EHR) system, and this contributes to the large share of costs in this category.

Not surprisingly, the second largest categories of costs are capital and maintenance costs, since it is expensive to build and maintain hospital facilities. On average, this represents nearly 30% of the total overhead costs at small hospitals.

The remaining 20% of overhead costs are associated with a variety of smaller functions, such as nursing management, medical records, housekeeping, dietary, and laundry services.

Since every hospital will need a minimum level of administrative services such as accounting, human resources, billing, etc. regardless of how many patients the hospital treats, one might expect that economies of scale would result in significantly lower administrative costs at the larger hospitals. However, the proportion of total expenses used for administrative costs is only slightly lower at larger hospitals.

Figure 3

Overhead Costs in Rural Hospitals

Medians for most recent three years available.

Total Service Line Costs

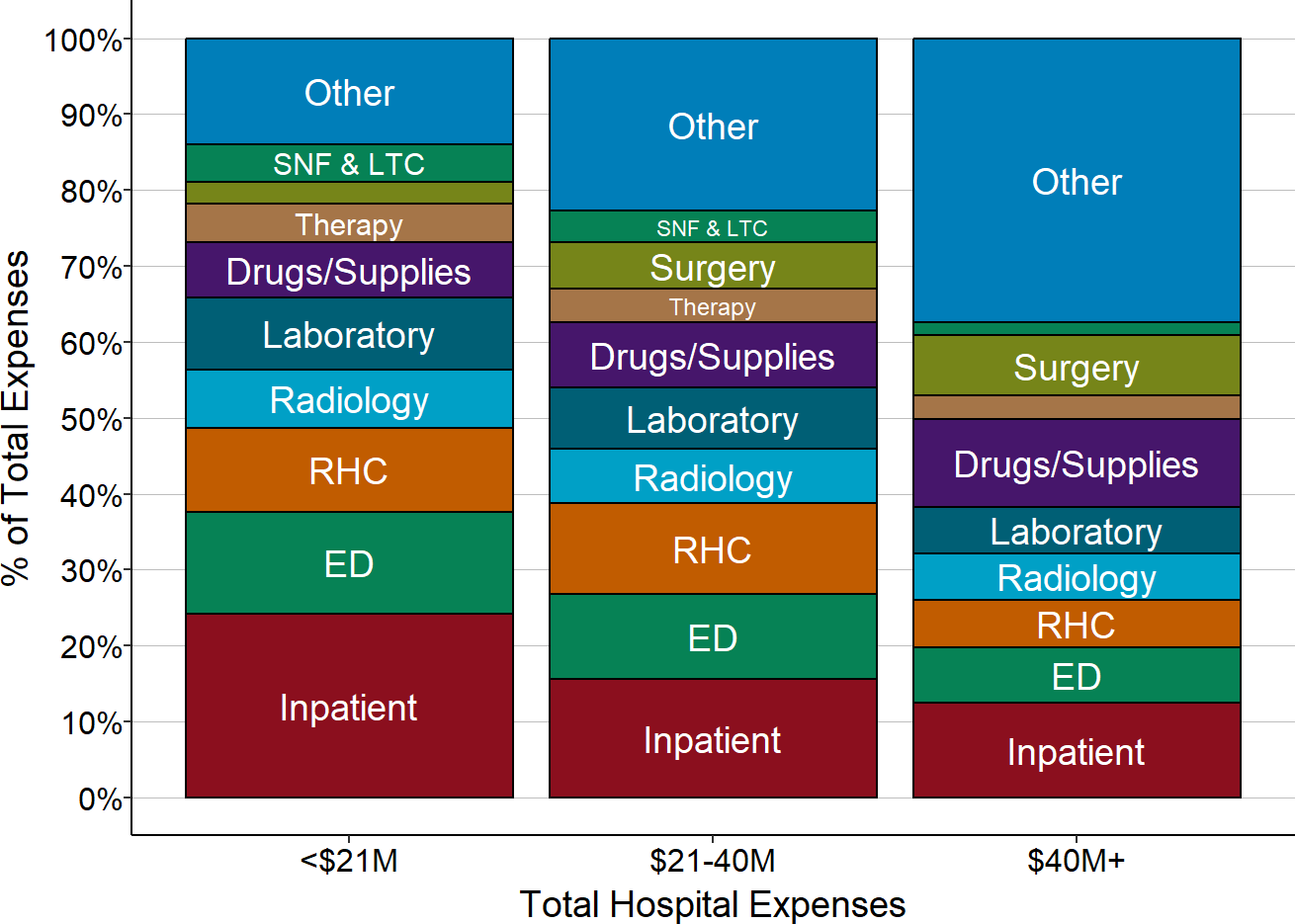

Hospitals are only paid for the services they provide to patients, so the payments the hospital receives for those services have to be adequate to cover not only the direct costs of the services, but also the overhead costs of the hospital. As a result, in order to set its charges for services, each hospital needs to allocate its overhead costs among the service lines.

The total cost of each service line will, on average, be about 60% higher than the direct costs when overhead costs are included. Since some services are more dependent on certain overhead cost centers than others, the percentages of overhead allocated to different service lines differ. For example, the inpatient unit is generally the largest user of the hospital’s dietary services, so a higher share of dietary costs is allocated to inpatient services.

Impact of Changes in the Number of Service Lines on Costs of Services

If a hospital is able to add an additional service line with little or no increase in administrative and overhead costs, the cost assigned to each of the existing service lines will decrease. This is because the hospital’s overhead costs are allocated across all of the hospital’s service lines, and so, all else being equal, the more service lines there are, the smaller the amount of overhead that will need to be allocated to each individual service line. As a result, the cost of a service line may differ at two hospitals not because of differences in the number of patients receiving the services, or differences in the staffing levels or wages paid to the staff, but because of how many other types of services each hospital offers.

An important corollary is that if a hospital eliminates a particular service line:

- the hospital’s total expenses will decrease by less than the total cost of the service line, because only a portion of the total cost allocated to the service line represents the direct costs of delivering that service; the rest represents a portion of the hospital’s general overhead expenses. While it may be possible for the hospital to make some reductions in one or more central administration cost centers when a service line is eliminated if the service line was a heavy user of those cost centers, in general, most of the hospital’s overhead costs will remain unchanged.

- The cost of every other service at the hospital will increase, because most of the overhead costs that had previously been allocated to the terminated service line now have to be recovered from the remaining service lines.

The Key Role of the Core Services on the Financial Viability of Small Rural Hospital

After allocation of overhead costs, the six core service categories still represent 60-70% of the total expenses at small rural hospitals. Because these services represent such a large proportion of the hospital’s total expenses, it will be difficult for a small hospital to be profitable if it does not receive payments for each of these core services that are adequate to cover the total (direct and overhead) costs of those service lines and if it cannot reduce the costs of the services to match the payments it is able to receive.

Figure 4

Total Service Line Costs in Rural Hospitals

Medians for most recent three years available.

The following sections examine the factors affecting the costs of each of these core services in greater detail.

The Cost of Delivering Rural Emergency Department Services

The single most essential service that rural hospitals provide is a 24/7 Emergency Department. Although emergency departments at small rural hospitals do not have the capability to treat severe trauma cases and emergencies that require highly-specialized services, neither do many urban hospital EDs. The primary roles all EDs perform are to quickly and accurately diagnose health problems, provide any necessary treatment to the patients, and transfer the small set of patients who need specialized care to a trauma center, stroke center, etc. Residents of rural communities who do not have access to an Emergency Department may be more likely to die or experience complications that could have been prevented.

This section will examine the costs involved in operating Emergency Departments at small, rural hospitals. The focus in this section will be on the basic ED visit itself, not on any additional services a patient may receive during the visit that are delivered by other hospital departments, such as a laboratory test or an imaging study. The costs of delivering those other services will be examined separately below.

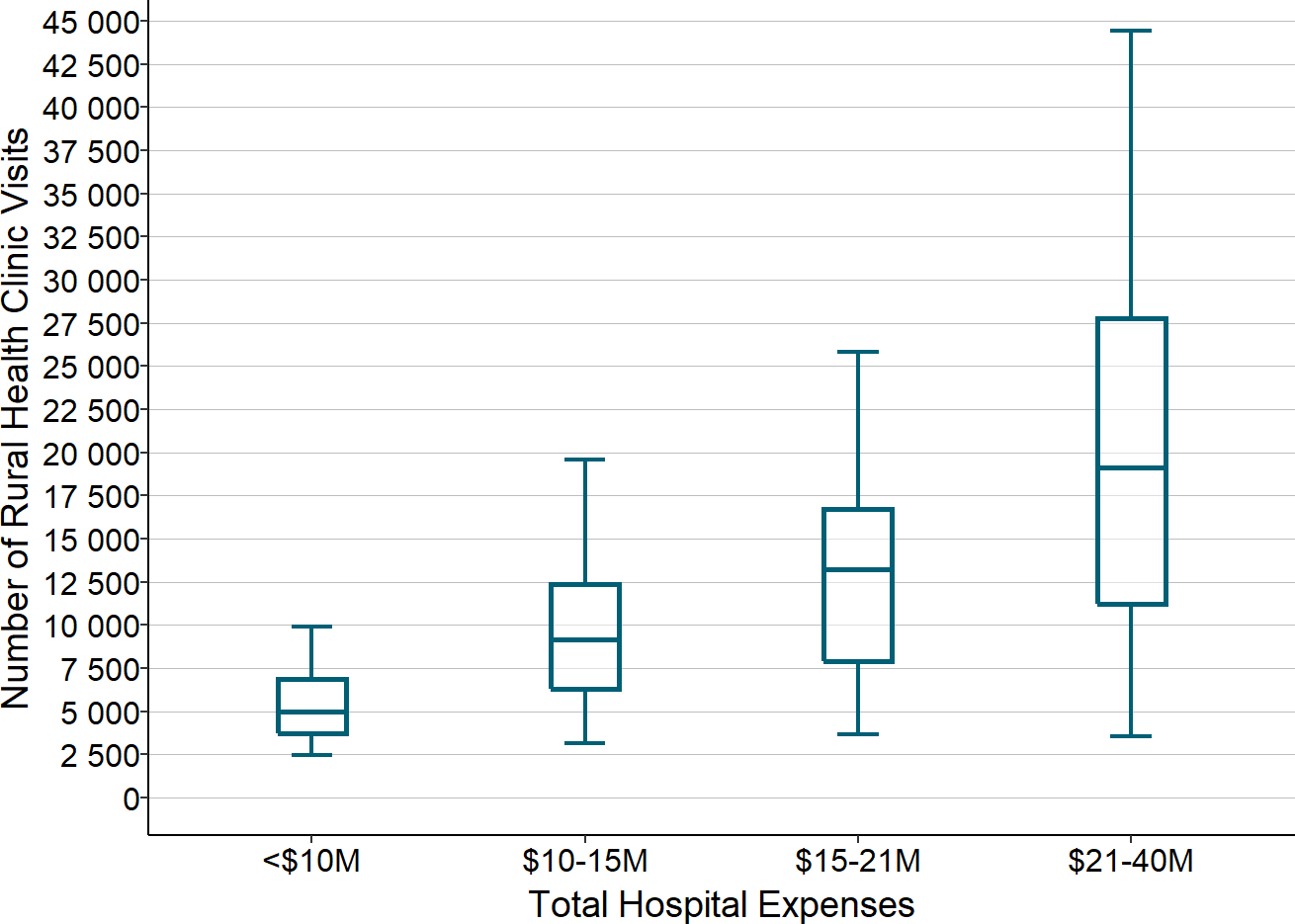

The Number of ED Visits at Small Rural Hospitals

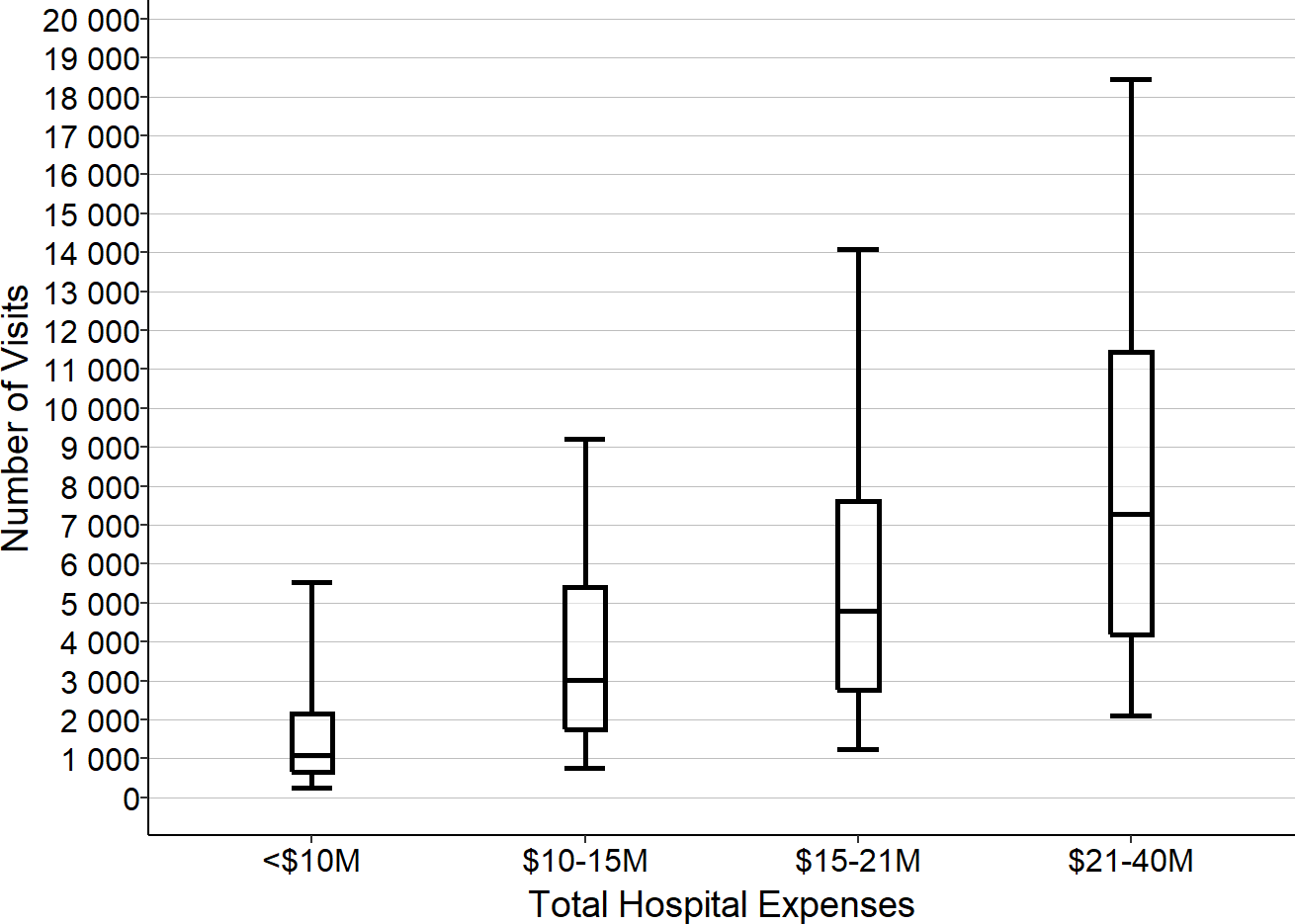

It is reasonable to expect that the cost of an Emergency Department will depend on how many visits the ED has. Rural hospitals that have a small number of inpatient admissions seem less small when one counts ED visits. The majority of small rural hospitals had fewer than 5,000 ED visits in 2017, i.e., about one visit every 2 hours.1 However, there is also considerable variation in the volume of ED visits among these hospitals; 10% of small rural hospitals (i.e., hospitals with less than $30 million per year in total expenses) had more than 11,000 ED visits in 2017, while another 10% had fewer than 1,000 visits.

Figure 5

ED Visits in Small Rural Hospitals, 2017

ED Visits are for 2017. Total Expense is for 2017 or for 2018 if 2017 is not available. Box shows 1st quartile, median, and 3rd quartile. Whiskers show 5th/95th percentile.

The large variation in the number of visits is due to a variety of factors, including the size of the community the hospital serves, the age and health status of the residents in the community, the number of businesses and workers in the community, the number of tourists who visit the community, and the community’s proximity to an interstate highway. Importantly, the number of ED visits will also depend on the availability of primary care in the community. For example, a hospital with no Rural Health Clinic will likely have more ED visits than a hospital that has an RHC because, without easy access to a primary care practice, more residents of the community will need to use the ED for non-emergency care.

The Cost of Operating an ED With 10,000 Visits Per Year

Each hospital’s cost report includes information on the total cost of operating its emergency department, but it is impossible to determine why some EDs are more expensive than others, even with the same number of visits, because there is very little information on the individual components of that cost. In particular, personnel costs would be expected to be the single largest component of the cost of an ED, but there is no information available on the number of physicians, nurses, or other staff who work in the ED, the number of hours they work, or the wage rates they are paid.2 However, since the ED needs to deliver high-quality care to patients who come with a wide range of problems at unpredictable times, one can estimate the level of staffing that a hospital would likely need in order to provide that care and how the staffing would change based on the volume of ED visits the ED receives.

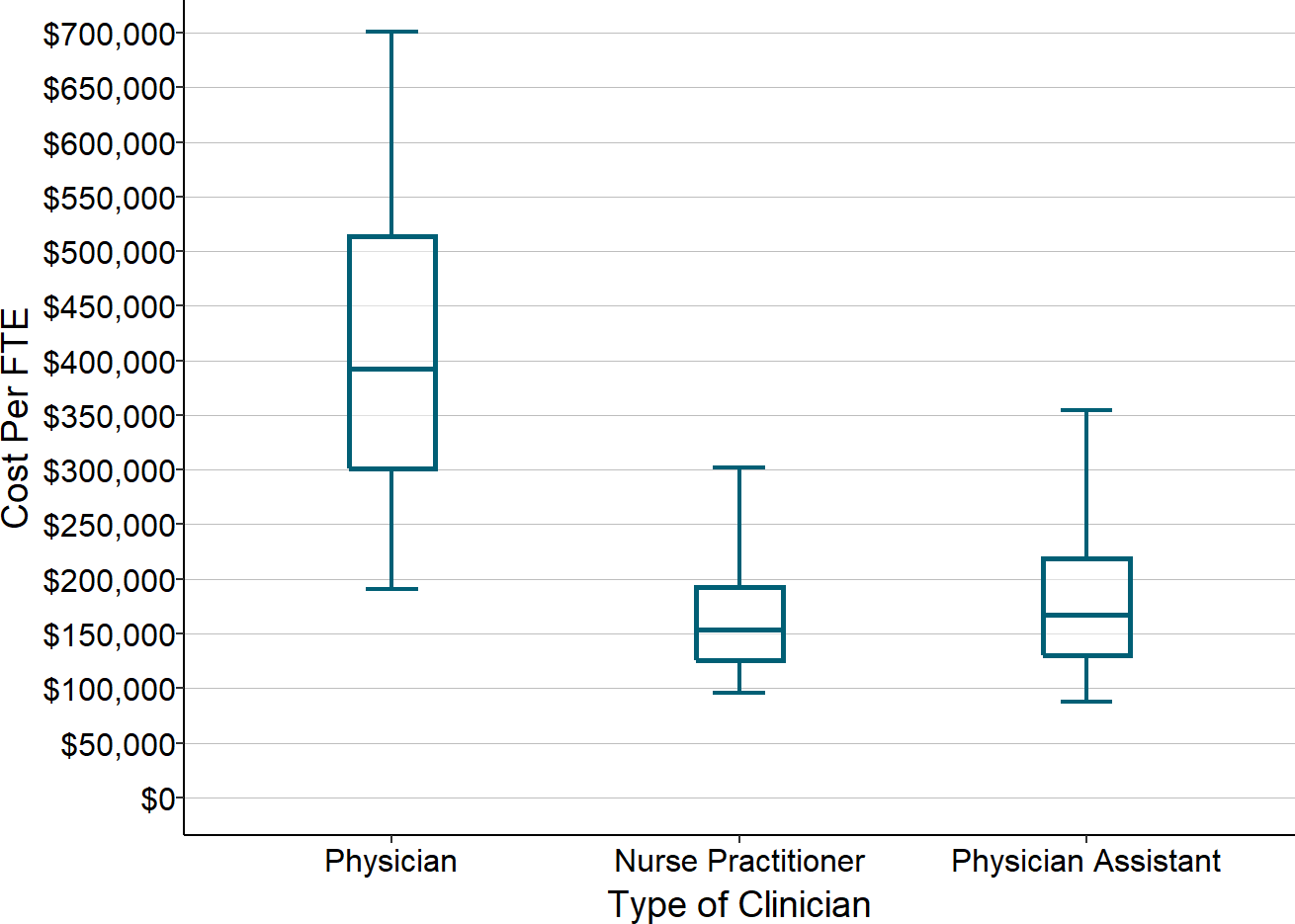

Physician Staffing

An Emergency Department that has 10,000 visits per year will see an average of one new patient every hour. Although not every patient who comes to the ED will need to see a physician, the ED will need to have a physician available in case they do, so there will have to be at least one physician on duty at all times.3

The volume of visits will generally be higher at certain times of the day, days of the week, and months of the year. For example, hospitals in communities with a large number of seasonal businesses, such as those in agriculture and tourism, will have higher volumes of ED visits during some months than others. However, since productivity standards for Emergency Departments generally assume that an ED physician can manage 2-3 visits per hour, it will generally not be necessary for an ED with 10,000 visits per year to have any more than one physician on duty at a time except during exceptional circumstances.4

However, since the ED is a 24/7 operation, the hospital will have to employ or contract with at least 4 full-time equivalent (FTE) physicians in order to have one physician in the ED at all times.5 (The exact number of physicians will depend on the number of shifts each physician is willing and able to work each week, the amount of time the physicians need to spend in continuing education, vacation days, etc. Some rural hospitals have to hire or contract with multiple physicians, each of whom come to the community for a short period of time, in order to have one “full-time equivalent physician.”)6

A hypothetical hospital that employs 4 FTE physicians to staff its ED will need to spend about $1.2 million to do so if it pays the physicians a salary of $120/hour with benefits equivalent to 20% of the salary. However, the actual cost of employing emergency physicians can vary significantly from community to community and from year to year depending on a hospital’s ability to attract and retain physicians. If a physician retires or resigns, a hospital will often need to hire a temporary physician to fill in while a permanent replacement is found, and the hourly cost of the temporary physician will generally be significantly higher than the cost of a permanent employee. Many rural hospitals contract with national ED staffing companies in order to eliminate the burden of maintaining a full staffing complement and to make the cost of staffing the ED more predictable7, but this can increase the overall cost of the ED because the staffing company has to be paid more than the physicians themselves receive.

Nursing Staff

In addition to a physician, the ED will also need at least one Registered Nurse (RN) around the clock to help in triaging, treating, and discharging patients. Since a nurse will generally need to spend more time with each patient than the physician does, it is possible that one nurse will be insufficient if multiple patients come to the ED at the same time or if the patients have more serious conditions. Small rural hospitals will typically deal with multiple visits or more serious cases by having a nurse from the inpatient unit come to the ED to provide assistance. (The need for this backup coverage will affect the nurse staffing levels the hospital will need in the inpatient unit, as discussed in a later section.) If the higher volumes occur at predictable times, the hospital may need to have two nurses on those shifts.

In order to have at least one nurse in the ED at all times, a hospital will have to employ as many as 5 FTE RNs.8 If the hypothetical hospital pays RNs $38/hour and provides benefits equal to 20% of salary, the total cost for the year will be more than $400,000. Here again, though, the cost of employing nursing staff will vary across communities and over time based on the ability of individual hospitals to attract and retain nurses and how much it costs them to fill vacancies temporarily while permanent replacements are being recruited.

Other Staff

The hospital will likely also need at least one non-clinical staff member to check patients in, help family members, etc. so that the physician and nurses can focus on providing clinical services to the patients. In order to have such a staff member in the ED at all times, the hospital will need to employ 4-5 FTEs. Assuming a $16/hour wage and 20% benefits, this will cost the hypothetical hospital an additional $170,000 per year.

Other Direct Costs

Almost all of the direct costs of operating an Emergency Department are associated with the physicians, nurses, and other staff. The costs of any medications used and other supplies that are billed to a patient separately are ordinarily assigned to a separate hospital cost center (these costs will be discussed separately in a later section), so non-personnel direct costs for the ED itself will generally be relatively small.

Indirect Costs

Finally, the operation of the ED also depends on the hospital providing space and utilities, maintenance for equipment, housekeeping, billing for patient visits, payroll and benefits for staff, medical records, etc. Consequently, a portion of the hospital’s costs for those activities must be allocated to the ED to properly represent the total cost of operating the ED. Typically, these indirect costs increase the total cost of an ED by about 50% beyond the personnel and other direct costs discussed above.9

Total Cost

These five components together imply that it will likely cost the hypothetical hospital nearly $3 million to deliver services to 10,000 ED patients during the year.

Figure 6

Cost of Emergency Department

at a Hypothetical Small Rural Hospital

ED Visits: 10,000

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Unit Cost | FTEs | Cost | |

| Physician | $120/hour | 4.0 | $994,000 |

| RN | $38/hour | 5.0 | $397,000 |

| Other Staff | $16/hour | 4.2 | $140,000 |

| Total Wages | $1,530,000 | ||

| Benefits | 20% of Wages | $306,000 | |

| Other Direct | $65,000 | ||

| Total Direct | $1,901,000 | ||

| Indirect Cost | 50% of Direct | $951,000 | |

| Total Cost | $2,852,000 | ||

The Cost of Operating an ED with More or Fewer Visits Per Year

How does the cost differ for an ED with more or fewer visits?

- For a hospital ED with 7,500 visits per year (i.e., 25% fewer than the 10,000 visits discussed above), there will still be almost one visit every hour, so this ED will also need one physician, one nurse, and a third staff member on duty round the clock. Other direct costs will be slightly lower with fewer patients and the indirect costs assigned to the ED may also be lower. Using the same assumptions about wage and benefit rates as for the hypothetical hospital discussed above, the total cost of the ED will be 96%-97% of the cost of the 10,000 visit ED, even though there are 25% fewer visits.

- Even if a hospital ED has only 5,000 visits per year, it will generally need to have a physician and nurse on duty around the clock, since it would have more than one visit every two hours on average. It is possible that the ED might be able to avoid using a third, non-clinical staff member during certain times of the day or week when the volume of visits is low, particularly if there is someone working in a different department at the hospital who can perform the same functions when needed, but this would only reduce the personnel costs by a relatively small amount. The total cost of an ED this size would likely still be more than 90% as much as the cost of the 7,500-visit ED, even though there are 33% fewer visits.

- If the ED has 12,500 visits per year (25% more than the 10,000 visits at the hypothetical hospital discussed earlier), it will have an average of 1.5 visits per hour, which can also generally be managed with a single physician on duty. However, because of the greater potential for delays during peak times, a hospital may choose to have an additional nurse on some shifts, which will increase the total number of nurses needed to staff the ED overall. As a result, direct costs and indirect costs may be 13% higher than at the ED with 10,000 visits.

- If the ED has 15,000 visits per year (50% more than the 10,000 visit ED), it will have an average of nearly 2 visits every hour. Because ED visits do not occur at a constant rate throughout the day and week, it is likely that the ED will have more than 3 visits per hour during its busiest times, which is more than a single physician can safely handle. Consequently, the hospital will likely need to hire additional physicians in order to have two physicians on duty during the high-volume shifts, in addition to a larger number of nurses. This would increase the cost of operating the ED by 45% over the cost at the 10,000 visit level, although this increase is still smaller than the 50% increase in visits.

Figure 7

Cost of Hypothetical Emergency Departments

with Different Numbers of Visits

| ED Visits | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ED Visits | 5,000 | 7,500 | 10,000 | 12,500 | 15,000 |

| Staffing (FTEs) | |||||

| Physician | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 6.0 |

| RN | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 7.5 | 7.5 |

| Other Staff | 2.0 | 4.2 | 4.2 | 4.2 | 4.2 |

| Cost | |||||

| Physician | $994,000 | $994,000 | $994,000 | $994,000 | $1,498,000 |

| RN | $397,000 | $397,000 | $397,000 | $593,000 | $593,000 |

| Other Staff | $67,000 | $140,000 | $140,000 | $140,000 | $140,000 |

| Total Wages | $1,457,000 | $1,530,000 | $1,530,000 | $1,726,000 | $2,230,000 |

| Benefits | $291,000 | $306,000 | $306,000 | $345,000 | $446,000 |

| Other Direct | $50,000 | $60,000 | $65,000 | $70,000 | $75,000 |

| Total Direct | $1,798,000 | $1,896,000 | $1,901,000 | $2,142,000 | $2,751,000 |

| Indirect Cost | $899,000 | $948,000 | $951,000 | $1,071,000 | $1,178,000 |

| Total Cost | $2,698,000 | $2,844,000 | $2,852,000 | $3,213,000 | $3,929,000 |

The Cost of Operating an ED with Even Fewer Visits

Most small rural hospitals have fewer than 5,000 ED visits per year. If the number of visits is less than about 10 per day (i.e., less than one visit every 2-3 hours), the hospital may be able to staff the ED differently, at least during some shifts. However, its ability to do so will depend on what other services the hospital offers, the availability of other physicians in the community and their willingness to help staff the ED, and the availability of remote support services from larger hospitals:

- If the hospital operates a Rural Health Clinic in or next to the facility where the ED is located, the physicians, nurse practitioners, or physician assistants who work in the clinic could leave the clinic and go to the ED to see a patient who comes to the ED during normal clinic hours.10

- At a hospital with a Rural Health Clinic(RHC), the RHC physicians/clinicians could also provide on-call coverage during night or weekend shifts when visit volumes are lower. If there are other primary care physicians in the community, they may also be willing to provide on-call coverage for the ED.

- A very low-volume ED could potentially use emergency-trained nurses to staff the ED if the hospital can arrange for telemedicine support from emergency physicians at a larger hospital.11

- If the nursing staff in the hospital’s inpatient unit is large enough (e.g., because the hospital has a large number of swing-bed patients), if the inpatient unit is close enough to the ED, and if the volume of ED visits is low enough, the hospital could rely on the inpatient unit nurses to staff the ED when a patient arrives, either during some shifts or all shifts, rather than having a nurse assigned exclusively to the ED.

The table below shows what the cost might be to operate a hypothetical ED that has 1,000 visits per year. This represents an average of fewer than 3 visits per day or less than one visit every 8 hours. The hospital where this ED is located is assumed to also operate a Rural Health Clinic staffed by both a physician and a Nurse Practitioner (NP), and the physician and the NP take responsibility for seeing patients who come to the ED during clinic hours. In addition, the Rural Health Clinic clinicians and one or more other physicians in the community are assumed to be willing to contract with the hospital to provide on-call support, i.e., they would agree to come to the ED quickly if and when a patient arrives. The example also assumes that there would be no dedicated nurses in the ED, and that one of the nurses from the hospital’s inpatient unit would go to the ED when a patient arrives. The total cost of this arrangement is just over $1 million. This is still about 40% of the cost of the ED with 10,000 visits, even though there are only one-tenth as many visits.

A hospital with 2,500 visits per year (about 6 visits per day) might still be able to rely on physicians at the Rural Health Clinic and in the community to diagnose and treat patients. However, it would be more problematic to rely solely on nurses from the inpatient unit to staff the ED, particularly during busier times, so it might need to employ additional nurses for this purpose. As shown in the table, the total cost might be about $1.6 million.

Figure 8

Cost of Hypothetical Emergency Departments with On-Call Staff

1,000 ED Visits

|

2,500 ED Visits

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unit Cost | FTEs | Cost | Unit Cost | FTEs | Cost | |

| Clinicians | ||||||

| Physician (PT) | $130/hour | 0.2 | $43,000 | $130/hour | 0.5 | $122,000 |

| NP/PA (PT) | $60/hour | 0.1 | $10,000 | $60/hour | 0.2 | $19,000 |

| On Call | $60/hour | $496,000 | $60/hour | $451,000 | ||

| Nurses | ||||||

| RN | $38/hour | 2.0 | $158,000 | |||

| RN (Shared) | $38/hour | 0.5 | $38,000 | $38/hour | 0.8 | $57,000 |

| Other Personnel | ||||||

| Other Staff | $16/hour | 2.0 | $67,000 | |||

| Total Wages | $587,000 | $873,000 | ||||

| Benefits | 20% of Wages | $117,000 | 20% of Wages | $175,000 | ||

| Other Direct | $10,000 | $25,000 | ||||

| Total Direct | $714,000 | $1,072,000 | ||||

| Indirect Cost | 50% of Direct | $357,000 | 50% of Direct | $536,000 | ||

| Total Cost | $1,071,000 | $1,609,000 | ||||

Variation in Costs for EDs of Similar Size

The cost estimates for the hypothetical EDs described above are based on multiple assumptions about the availability and cost of staff in the ED and other costs in the hospital, some or all of which may not be realistic for hospitals in every community. As a result, the actual costs in individual hospitals will vary significantly from community to community; moreover, costs can change from year to year for reasons beyond the control of the hospital. For example:

- There may be no primary care physician in the community or no physician who is willing to provide on-call coverage for the ED, in which case the hospital would have to hire dedicated physicians for the ED.

- A hospital located in a more remote area may have greater difficulty attracting and retaining physicians to staff the ED, and may need to pay physicians more to work there.

- If a physician resigns or retires, the hospital will often need to engage a locum tenens physician until a replacement is found, and it will generally need to pay a much higher hourly rate for the temporary physician, for their travel costs, etc.

- A hospital with large seasonal differences in the numbers of ED visits may need to have higher staffing levels during a portion of the year that cannot be offset by smaller staffing levels during the remainder of the year.12

- A hospital that does not have easy access to a part-time nursing workforce may need to employ a larger complement of nurses in order to ensure it has adequate coverage for illnesses, vacations, training, etc.

- A hospital located in an area where health insurance is more expensive will incur higher benefit costs for its employees.

- A hospital that offers a broader array of services will need to assign a smaller portion of its administrative costs to the ED than a hospital with a more limited set of services. For example, if the hospital operates a Rural Health Clinic, a portion of the hospital’s general administrative costs will be allocated to the RHC in addition to the ED, reducing the cost assigned to the ED.

In some cases, favorable and unfavorable differences in different aspects of cost may offset each other, but it is more likely that hospitals experiencing higher costs in one component of costs will also have higher costs in other areas. The table below shows an example of how the total cost of two EDs with similar numbers of ED visits can differ dramatically due to the combined effects of multiple small differences in staffing levels, wage rates, benefit rates, and overhead allocations. Hospital A and Hospital B have the same number of ED visits and they each have one physician, one nurse, and one other staff member on duty at any given time. However, Hospital B needs slightly more physicians and nurses in order to achieve this level of staffing, it has to pay the employees more than Hospital A, and it has fewer service lines overall, so it has to allocate a higher share of administrative costs to the ED. The combined result is that Hospital B’s overall cost for the ED is 26% higher than the cost at Hospital A.

Figure 9

Impact of Variations in Unit Costs on Total Emergency Dept. Cost

Hospital A (5,000 ED Visits)

|

Hospital B (5,000 ED Visits)

|

Difference | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unit Cost | FTEs | Cost | Unit Cost | FTEs | Cost | ||

| Physician | $115/hour | 4.0 | $952,000 | $125/hour | 4.5 | $1,170,000 | 23% |

| RN | $37/hour | 5.0 | $385,000 | $39/hour | 5.0 | $406,000 | 5% |

| Other Staff | $15/hour | 2.0 | $62,000 | $17/hour | 2.0 | $71,000 | 15% |

| Total Wages | $1,400,000 | $1,646,000 | 18% | ||||

| Benefits | 18% of Wages | $252,000 | 22% of Wages | $362,000 | 44% | ||

| Other Direct | $40,000 | $60,000 | 50% | ||||

| Total Direct | $1,692,000 | $2,069,000 | 22% | ||||

| Indirect Cost | 48% of Direct | $812,000 | 52% of Direct | $1,076,000 | 33% | ||

| Total Cost | $2,504,000 | $3,144,000 | 26% | ||||

Because the unit costs can vary for many reasons beyond the control of a small rural hospital, the staffing and compensation levels for the hypothetical hospital EDs shown in Figures 3-7 and 3-8 do not represent what any individual hospital ED should cost or what the differences in costs between EDs of different sizes should be. However, the cost models for the hypothetical hospitals do provide useful insights into what it can cost to operate small rural hospital EDs and the potential magnitude of differences based on size.

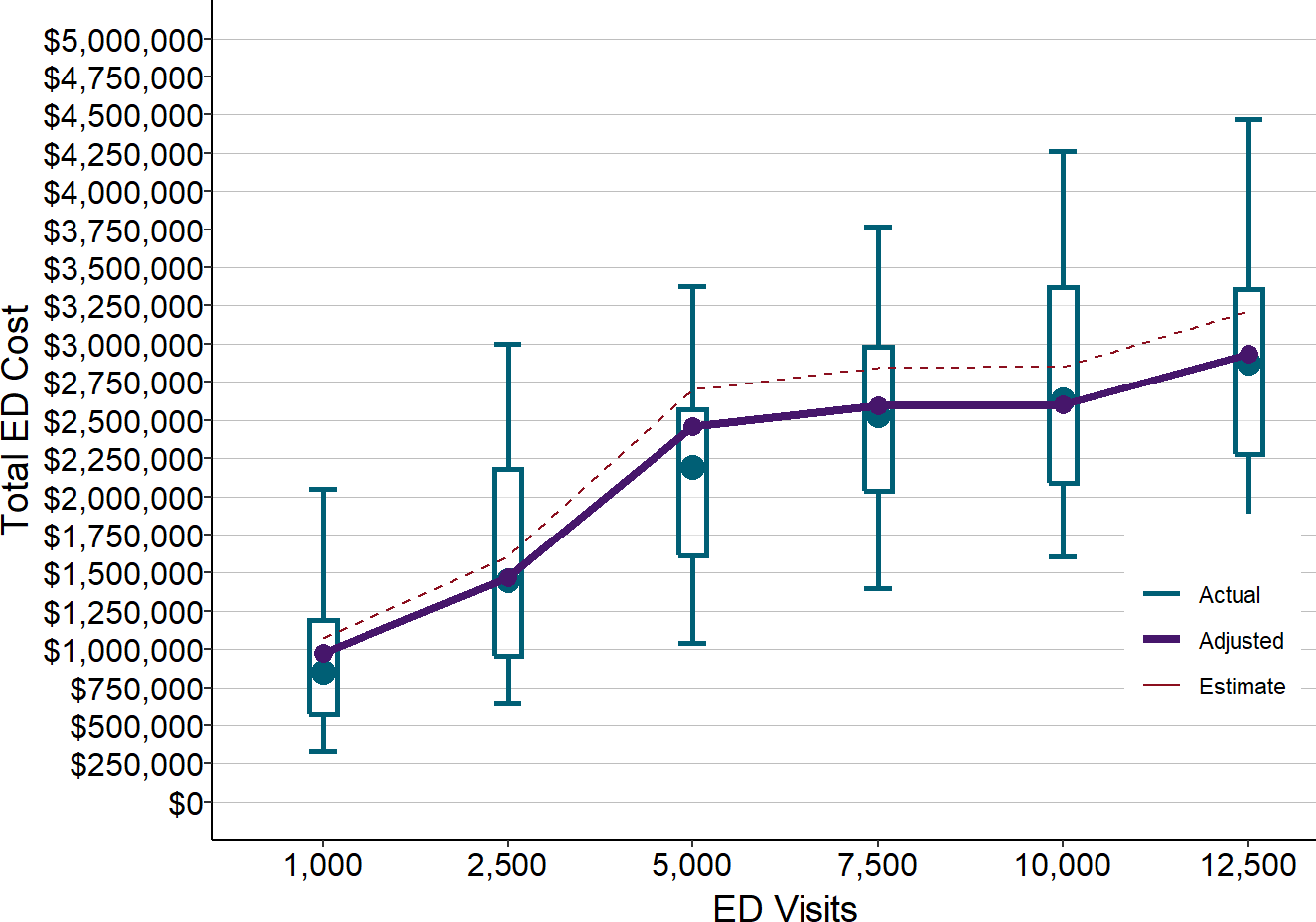

The amounts calculated above for the hypothetical EDs are very similar to the median actual costs of Emergency Departments at small rural hospitals, after adjusting the estimates downward to reflect several years of inflation since 2016-18.13 There is also significant variation in the actual amounts that small rural hospitals spend to operate Emergency Departments with similar numbers of visits, much of which is likely due to the kinds of factors described above.

Figure 10

ED Actual and Estimated Costs in Small Rural Hospitals

Actual amounts are for rural hospitals with less than $30 million in total expenses in 2016-18. Estimates (dotted line) are from Figure 7 and Figure 8. Adjusted values (solid line) are the estimated values reduced to reflect inflation between 2017 and 2020.

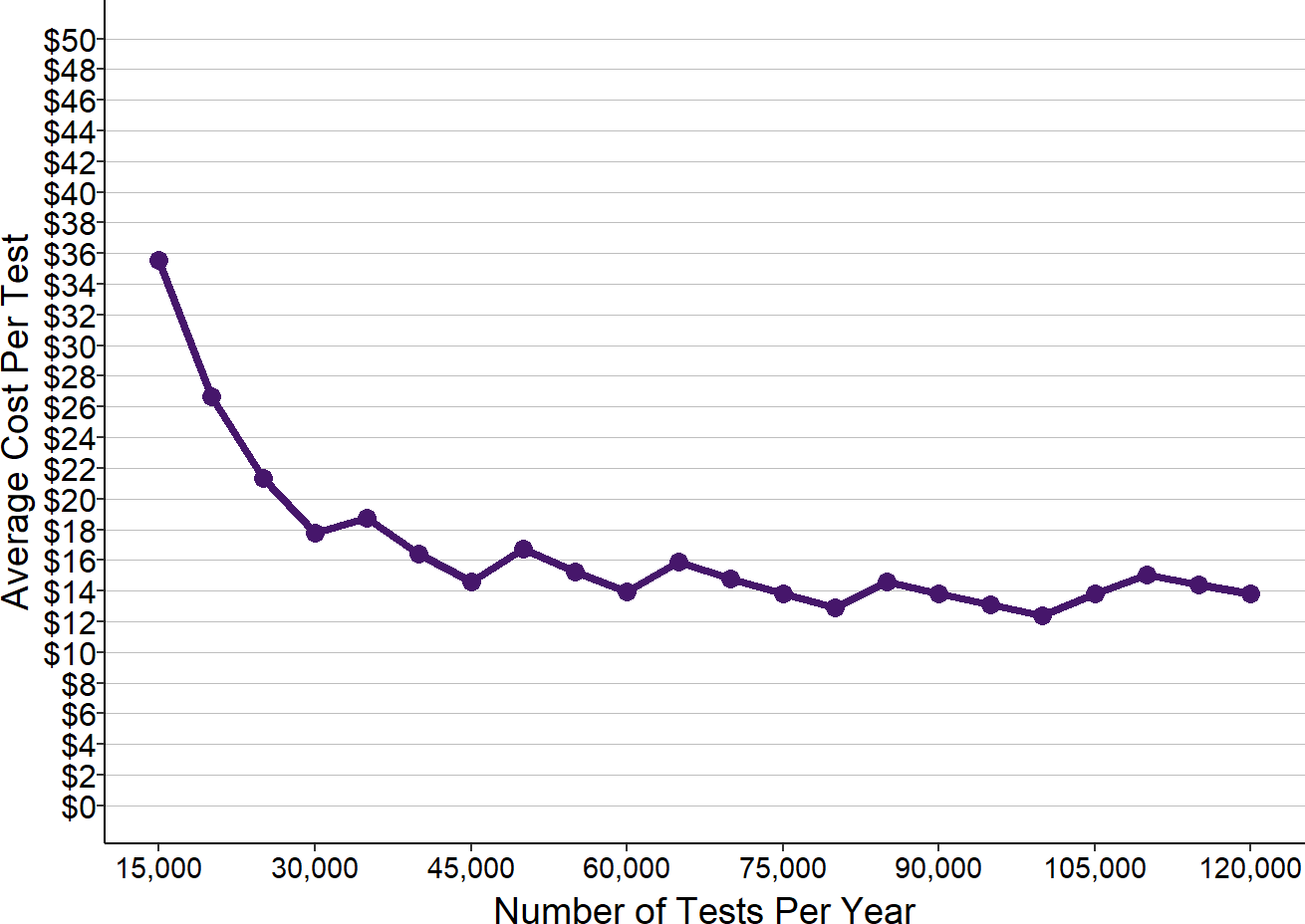

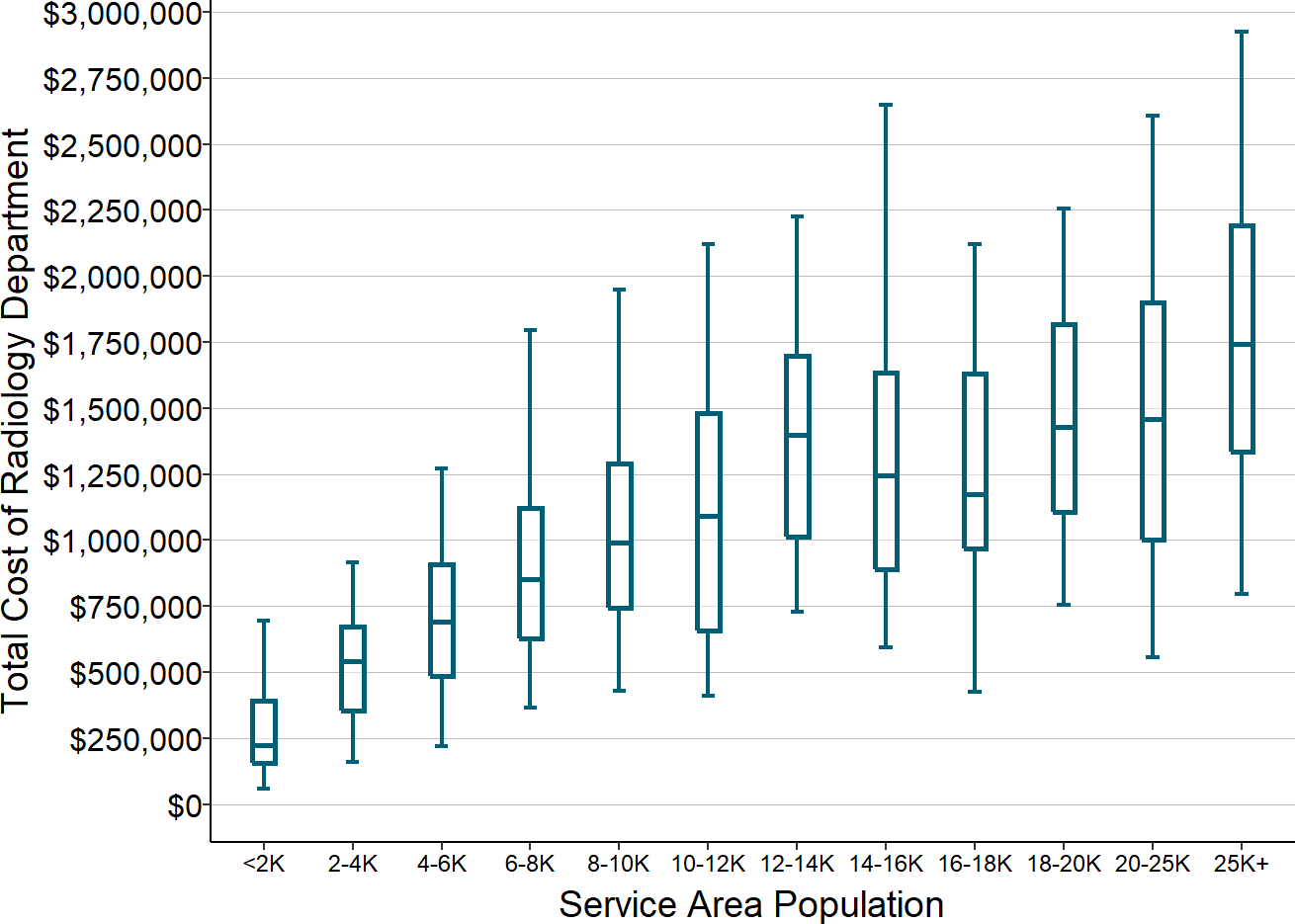

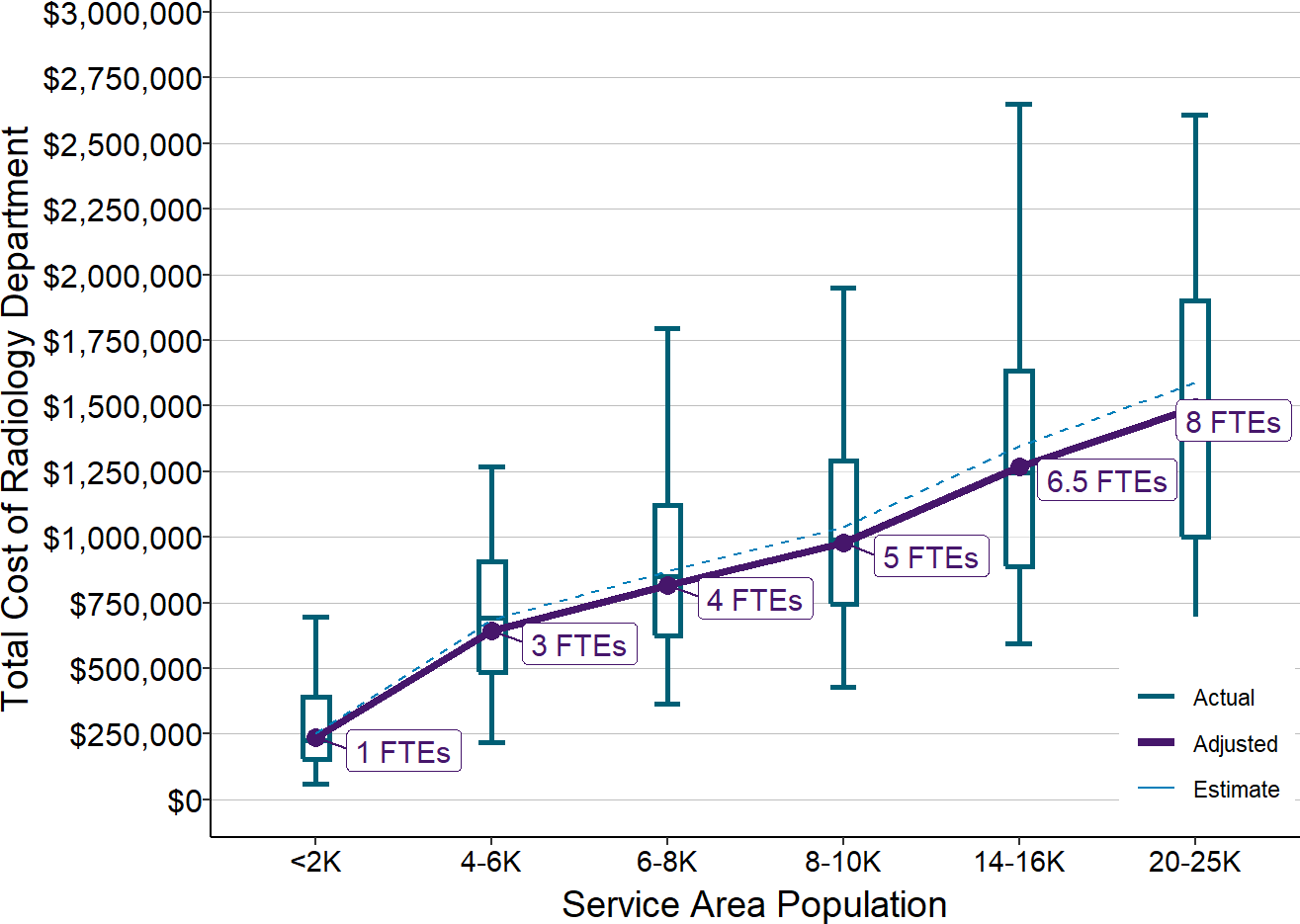

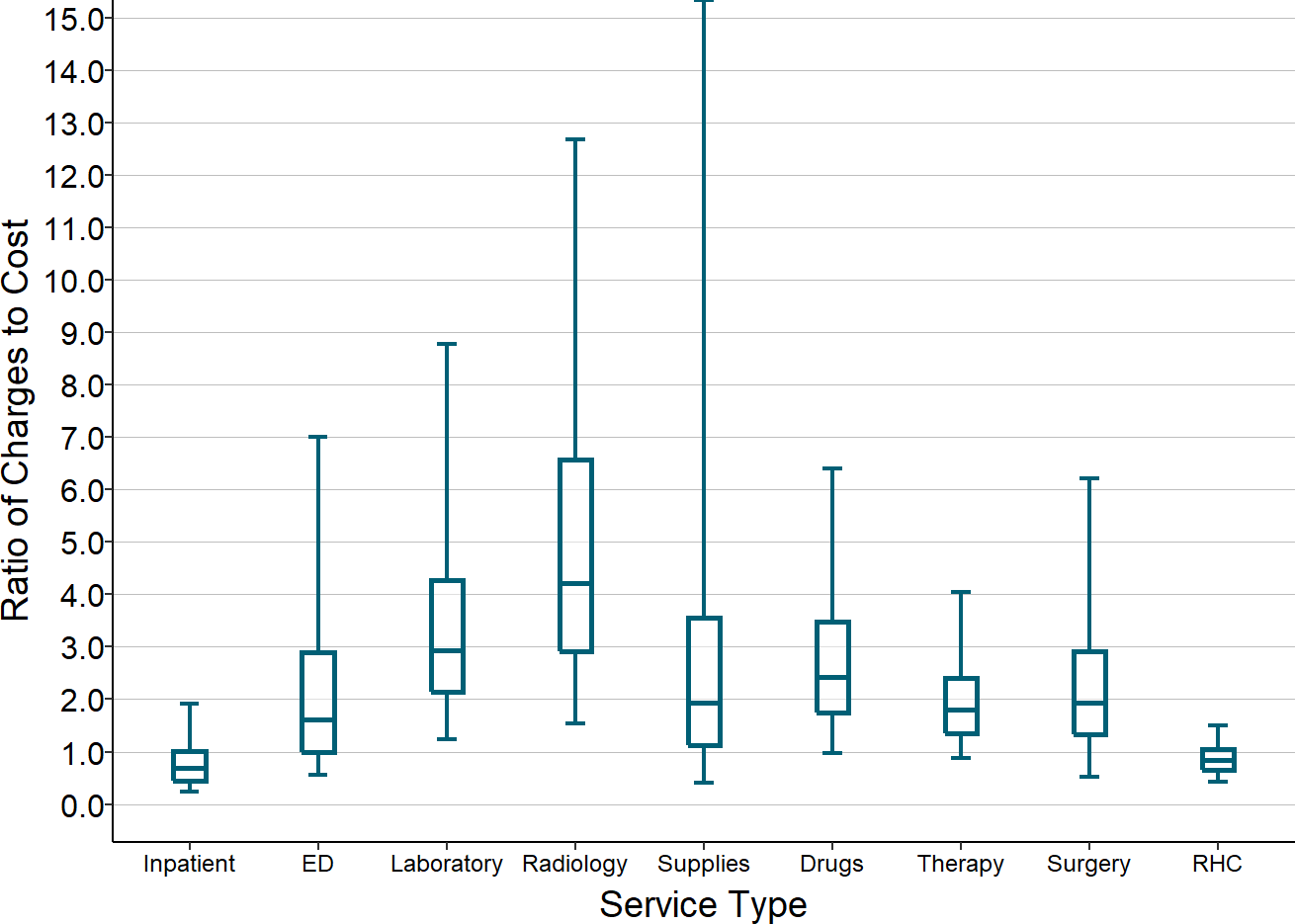

Differences in the Cost of an ED Visit at Different Hospitals

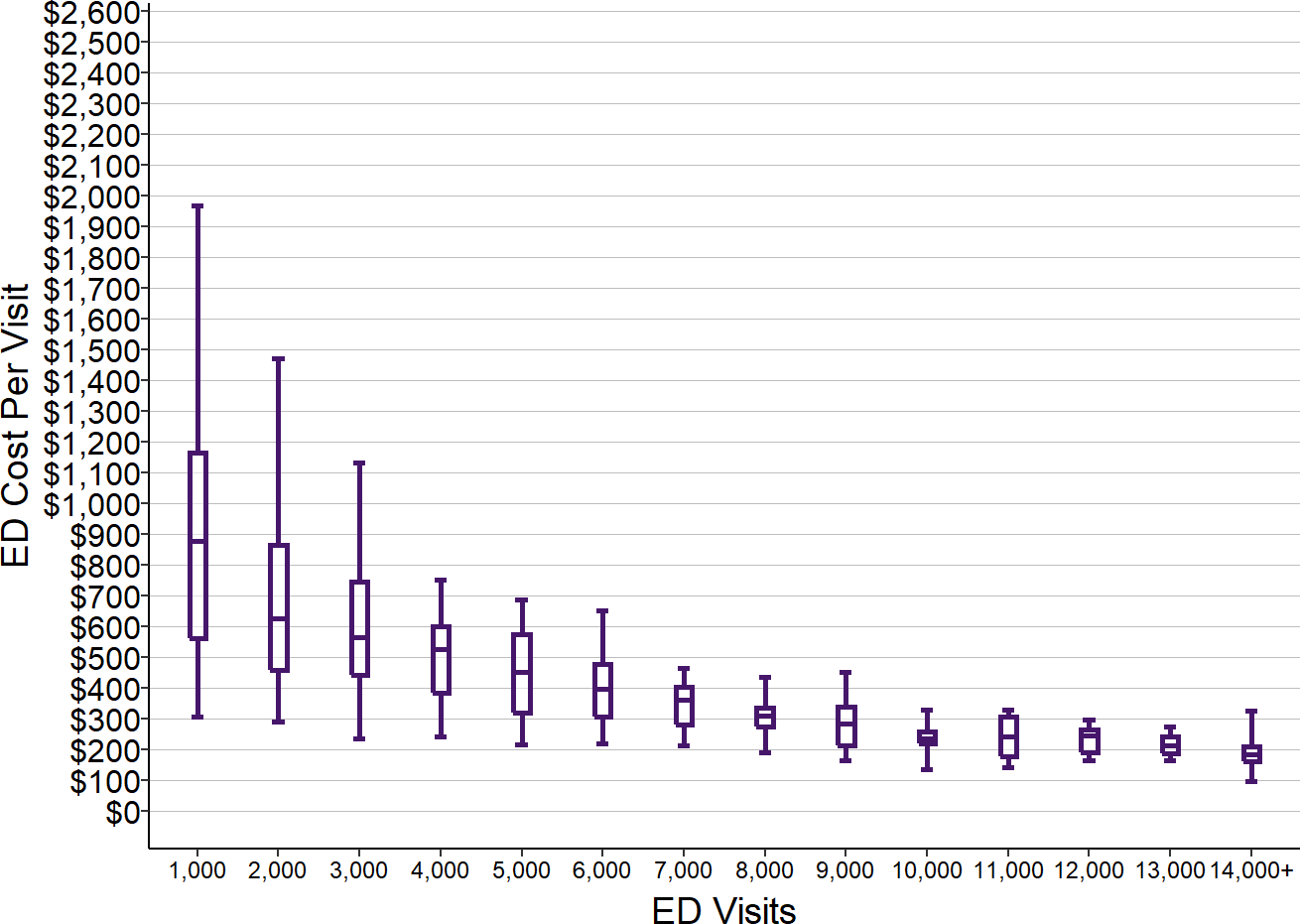

The total cost of operating an ED is generally not directly proportional to the number of ED visits because the same level of staffing is needed for a wide range in the number of visits. This means that the average cost per visit in the ED will be significantly lower at a hospital with more ED visits. While the estimated total cost of operating the hypothetical ED with 12,500 visits was 13% more than the cost of an ED with 7,500 visits, the cost per visit at the 12,500-visit ED is 32% lower because there are 67% more visits. The average cost per visit at the hypothetical ED with 1,000 visits is over $1,000, more than 4 times the average cost per visit at the hypothetical ED with 12,500 visits, because the total cost of the ED is 1/3 as much even though there are only 10% as many visits.

Figure 11

Cost Per Service at Different Service Volumes in Emergency Depts.

| ED Visits | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ED Visits | 1,000 | 2,500 | 5,000 | 7,500 | 10,000 | 12,500 | 15,000 |

| Cost | |||||||

| Total Cost | $1,071,000 | $1,609,000 | $2,698,000 | $2,844,000 | $2,852,000 | $3,213,000 | $3,929,000 |

| Cost Per Service | |||||||

| Cost Per Visit | $1,071 | $643 | $540 | $379 | $285 | $257 | $262 |

However, once the number of visits reaches a certain level, the cost per visit begins to stabilize because more of the total cost represents the “semi-variable” cost of additional physicians and nurses needed to handle additional visits, rather than the fixed cost of the minimum capacity to handle even a small number of visits. For example, even though the total cost of the ED with 15,000 visits is 45% higher than the cost of the ED with 10,000 visits, the cost per visit is only slightly less.

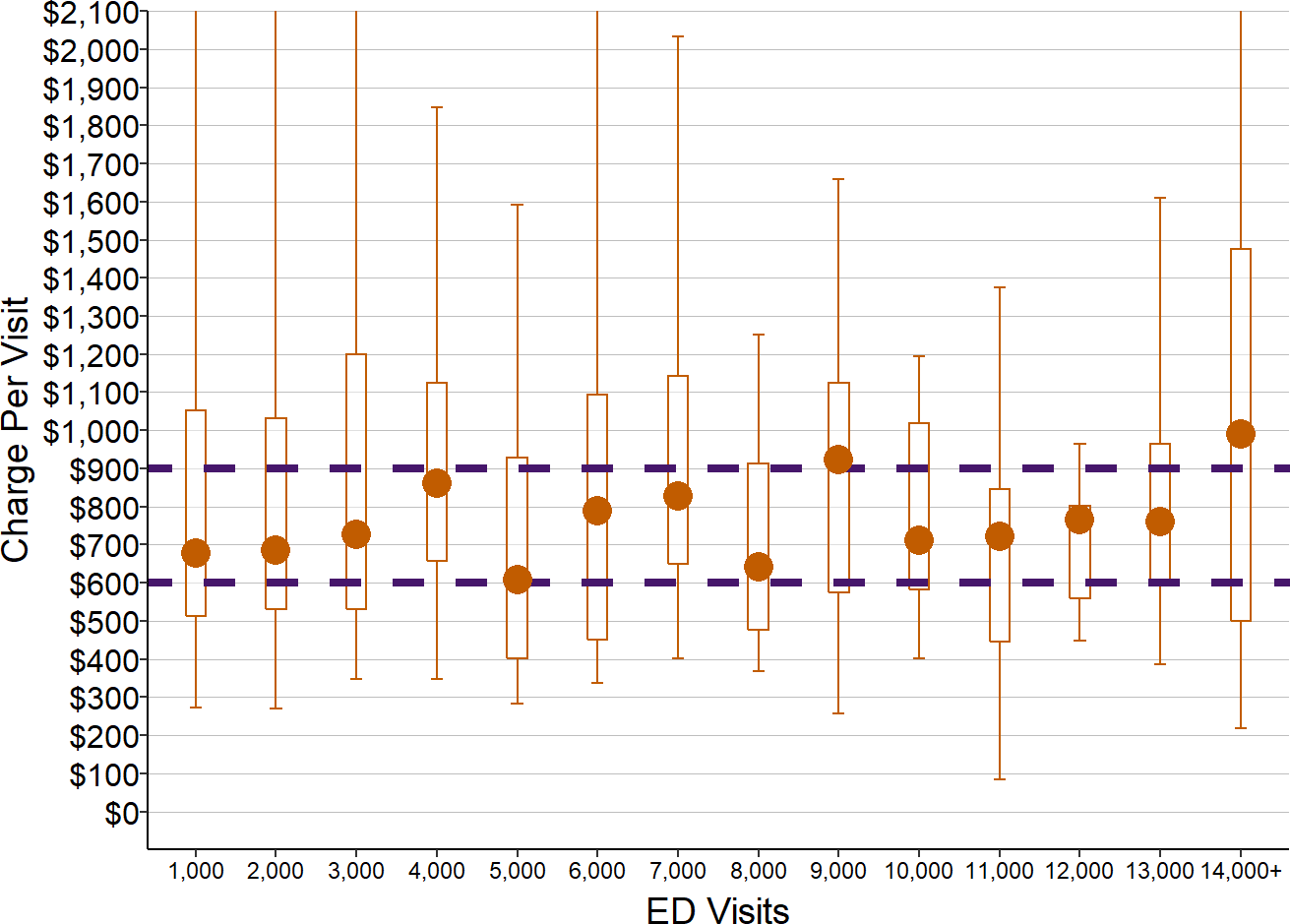

As shown below, the actual cost per visit at rural hospitals follows this pattern. The median cost per ED visit at hospitals with small number of visits is double, triple, or even more than quadruple the median cost per visit at hospitals with larger number of visits.

There is much greater variation in the cost per visit among the smallest hospitals, which likely reflects the variety of challenges in staffing such EDs in different communities.14

Figure 12

Cost Per ED Visit in Small Rural Hospitals

Values shown are for rural hospitals <$30M total expenses. ED Visits are from 2017. ED cost is the median for each hospital in 2016-18.

The cost models of the hypothetical EDs make it clear that the primary reason smaller hospitals have higher costs per visit than larger hospitals is not because the smaller hospitals are “inefficient” in delivering services, but because they have to incur a minimum level of fixed costs in order to operate an ED regardless of how many visits the ED actually receives. As a result, any effort to evaluate the relative efficiencies of hospitals based solely on differences in their average cost per ED visit will lead to erroneous conclusions.

Impact of Changes in Volume on the Cost Per Visit

Because the cost of operating an ED is not directly proportional to the number of visits, the average cost per visit at a hospital ED will vary from month to month and year to year based on the number of people who happen to visit the ED during that particular period of time.

For example, the table below shows a hypothetical hospital with 5,000 ED visits; the total estimated cost of operating the ED is $2.7 million, using the same assumptions about staffing and unit costs shown earlier. If the hospital has exactly 5,000 visits, its average cost per visit will be $540.

If the hospital happens to get only 4,500 visits during the year instead of 5,000, it will not be possible to reduce the staffing in the ED, so the cost of operating the ED will not change. However, dividing the same cost by 10% fewer visits causes the average cost per visit to increase by $59, a more than 11% increase.

Similarly, if the hospital ED happens to receive 5,500 visits during the year instead of 5,000, no additional physicians, nurses, and other staff will be needed, so the cost of operating the ED will not change. But with 10% more visits, the average cost per visit will decrease by $50, a reduction of more than 9%.

As a result, the average cost per visit at any hospital will vary from year to year, not because the hospital has become more or less efficient in delivering services, but simply due to the inherently random nature of the number of ED visits.

Figure 13

Changes in Cost Per Visit When Number of Visits Changes

Base Volume

|

Lower Volume

|

Higher Volume

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount | Amount | Change | Amount | Change | |

| ED Visits | |||||

| ED Visits | 5,000 | 4,500 | −10% | 5,500 | 10% |

| Cost | |||||

| Physician | $994,000 | $994,000 | 0% | $994,000 | 0% |

| RN | $397,000 | $397,000 | 0% | $397,000 | 0% |

| Other Staff | $67,000 | $67,000 | 0% | $67,000 | 0% |

| Total Wages | $1,457,000 | $1,457,000 | 0% | $1,457,000 | 0% |

| Benefits | $291,000 | $291,000 | 0% | $291,000 | 0% |

| Other Direct | $50,000 | $50,000 | 0% | $50,000 | 0% |

| Total Direct | $1,798,000 | $1,798,000 | 0% | $1,798,000 | 0% |

| Indirect Cost | $899,000 | $899,000 | 0% | $899,000 | 0% |

| Total Cost | $2,698,000 | $2,698,000 | 0% | $2,698,000 | 0% |

| Cost Per Service | |||||

| Cost Per Visit | $540 | $599 | 11% | $490 | −9% |

The Problems Caused by Visit-Based Fees

Although the cost of operating a hospital ED is not directly proportional to the number of ED visits, the hospital’s revenue usually is. Most of the revenue hospitals use to cover ED costs comes from a fee paid each time a patient visits the ED. As a result, when the number of visits increases, revenue increases proportionally, and when the number of visits decreases, so does revenue.15 (Separate fees are paid for the other services the patients receive, such as lab tests or x-rays, and those will be discussed in a later section in conjunction with the costs of those services.)

This approach to payment causes two serious problems for small rural hospital EDs:

- Fees that are adequate for larger hospitals will not be adequate for smaller hospitals; and

- The adequacy of a visit fee depends on how many patients make ED visits.

Fees for ED visits that are adequate for larger hospitals will cause losses at small rural hospitals.

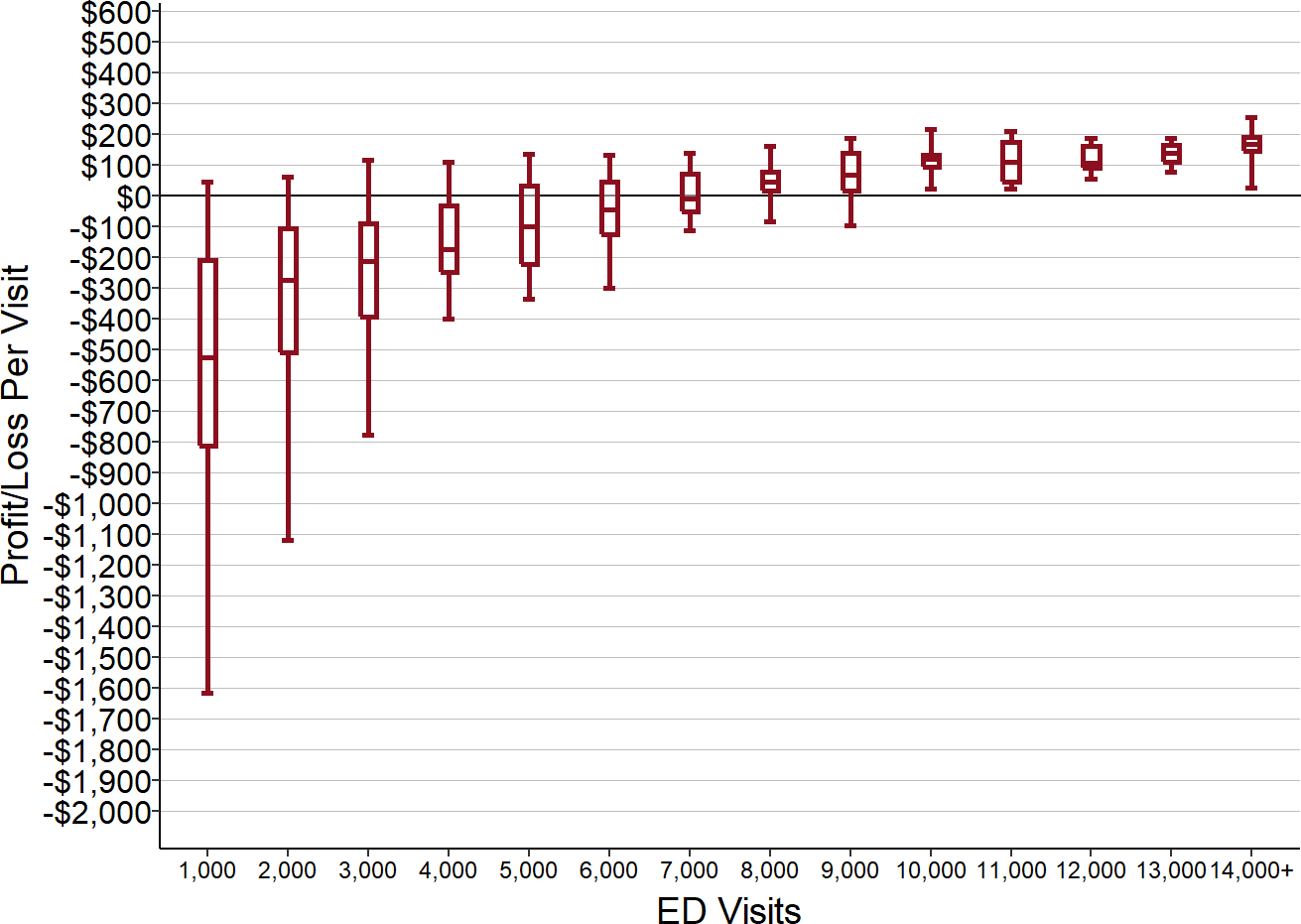

Figure 12 showed that for EDs with 7,000 visits, the median cost per visit was $400, with much higher costs per visit at smaller EDs. But as shown in Section 2, the median payments by private health plans for ED visits at small rural hospitals ranged from under $200 to $350 in the states examined. If the payment per visit is $200 - $350 when the cost per visit is $500 - $700 or more, the hospital will be unable to cover more than half of the cost of operating the Emergency Department.

As shown below, if every hospital in Figure 12 was paid $350 per ED visit16, the hospitals with 8,000 or more visits would have made a profit on every visit, whereas almost every hospital with less than 4,000 visits would have lost money on every visit. Most of the hospitals with the largest numbers of visits could have covered their costs or made a small profit even with a payment of $250 per visit, but a payment that low would have increased the size of the losses at the smallest hospitals and caused additional small hospitals to have losses.

Figure 14

Profit/Loss Per ED Visit with $350 Per Visit Fee

Values shown are the ED cost per visits amounts from Figure 12 subtracted from $350.

Some small hospitals will have larger losses than others, even if they receive the same payment per visit and have the same number of visits, if they have to pay more to attract and retain an adequate number of physicians and nurses in the community where they are located. In the example shown in Figure 9, even though Hospital A and Hospital B have the same number of ED visits and the same level of staffing in the ED on any given day, Hospital B would lose far more than Hospital A if they were both paid the same amount for a visit.

An unexpected illness or resignation of physicians or nurses will generally require the hospital to hire temporary physicians or nurses. This is far more likely at a small rural hospital because the smaller staff provides less capacity to cover temporary vacancies and because it takes longer to fill vacancies. Moreover, the higher cost of a temporary employee combined with the cost required to recruit a new employee will cause a larger percentage increase in personnel costs at a hospital that has a small number of employees to begin with. As a result, a visit fee that appeared to be adequate at the beginning of the year may no longer cover costs, and the hospital would experience losses by the end of the year.

The adequacy of any visit fee amount depends on how many patients actually have emergencies.

The problem with ED visit fees is not just the amount of payment, but the method of payment. Because revenues change in direct proportion to the number of visits when visits increase or decrease but costs may barely change at all, even small changes in the number of ED visits can result in larger or smaller losses or profits.

The table below shows that for the hypothetical hospital shown previously, if the ED receives 5,000 visits, a payment of $540 per visit would be just enough to cover the costs of the ED. However, if the fee is set at that level and the hospital only receives 4,500 visits (10% fewer than expected), the reduction in revenue would result in an 10% loss. Conversely, if the hospital happened to experience a 10% increase in the number of ED visits, it would receive a windfall profit of 10%.

It is impossible to predict exactly how many ED visits any hospital will have, so even if the visit fee appears adequate at the beginning of the year, it may well turn out to be inadequate by the time the year ends.

Figure 15

Impact on ED Margin When Number of Visits Changes

Baseline

|

Fewer Visits

|

More Visits

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount | Amount | Change | Amount | Change | |

| ED Visits | 5,000 | 4,500 | −10% | 5,500 | 10% |

| Payment Per Visit | $540 | $540 | 0% | $540 | 0% |

| Total Revenue | $2,700,000 | $2,430,000 | −10% | $2,970,000 | 10% |

| Total Cost | $2,698,000 | $2,698,000 | 0% | $2,698,000 | 0% |

| Margin | $2,000 | ($268,000) | −13,500% | $272,000 | 13,500% |

| Pct Margin | 0% | −10% | −11,083% | 10% | 11,083% |

Tradeoffs Between Quality, Affordability, and the Financial Viability of Services

The problems with current payments mean that many small rural hospitals face problematic choices between delivering the highest-quality care at an affordable cost and avoiding financial losses.

Financial Penalties for Using Full-Time Emergency Physicians vs. Part-Time Providers

A patient experiencing an emergency will receive much faster care if there is a physician present in the ED at all times than if a physician has to be called in to the ED from home. Moreover, an emergency physician will have more training and experience in handling a wide range of emergencies than most primary care physicians. Consequently, it is preferable for the hospital to have emergency physicians on duty around the clock than to rely on on-call coverage from primary care providers.

However, the cost will likely be much higher to employ full-time emergency physicians than to rely on on-call providers, and it will often be more difficult and expensive to attract and retain full-time emergency physicians to work in an ED where they will only spend a fraction of their time actually treating patients. The increase in the median cost per visit between 3,000 and 4,000 visits that can be seen in Figure 12 is probably at least partially due to the fact that some hospitals with 3,000 visits have the ability to use part-time providers who are not emergency physicians to staff their ED, whereas hospitals with more visits will need to use full-time physicians, and it is much more expensive to do the latter than the former.

Because of the higher cost, a hospital will have to charge more per visit in order to employ full-time emergency physicians instead of using only part-time providers, and this will cause higher financial burdens on patients and increase the hospital’s bad debt. If patients’ health insurance plans refuse to pay the higher charges, the hospital will lose money.

Financial Penalties for Improving Care Management and Preventive Care

Many patients come to an ED for treatment of a problem that could have been prevented through better management of a chronic disease or better preventive care. For example, patients with asthma or COPD may experience exacerbations and breathing problems if they fail to take the appropriate medications, and individuals are more likely to get sick if they are not properly vaccinated for influenza or pneumonia.

However, the hospital is paid when the patient comes to the ED and it is not paid if the patient has no problems, so the hospital is penalized financially if the residents of the community are healthier. If primary care practices in the community or the hospital’s own Rural Health Clinic provide better care management and preventive care for their patients, the hospital ED could lose revenues as a result.

Financial Penalties for Charging Affordable Prices

As shown below, the median charge for an ED visit is generally between $600 - $900 at both smaller and larger rural hospitals. Based on the cost per visit data in Figure 12, if the hospitals were actually paid that amount, it would be more than adequate to cover the costs of an ED visit at all but the very smallest hospitals. However, that charge would be unnecessarily high at hospitals with larger numbers of visits.

Figure 16

Estimated Charge Per ED Visit at Small Rural Hospitals

Amounts shown are estimated using median charges for 2016-18 and ED visits in 2017 for rural hospitals with less than $30 million in total expenses.

However, the chart also shows that the charges for ED visits vary dramatically among hospitals. Most health insurance plans demand that hospitals, physicians, and other healthcare providers provide large discounts on their standard prices in order to contract with the health plan. In order to give a discount, a hospital has to charge far more for a service than the cost of delivering the service so that the actual amount of payment the hospital receives for the service is sufficient to cover the cost. Typical commercial contract discounts are 50%, 67%, 75% or an even higher percentage of the charge, so the hospital has to set the charge at 2, 3, 4, or more times what the service actually costs.

However, these high charges make the hospital’s services unaffordable for patients who do not have insurance, and this can discourage patients from getting care that they need. If patients receive services but cannot afford to pay what the hospital charges, the hospital will have large amounts of patient bad debt and the patients could face bankruptcy.

If the hospital charges lower amounts for its services that patients could afford to pay, the discounts demanded by health insurance companies could result in “allowed amounts” that are lower than the hospital’s cost of delivering services. Since there are far more patients with insurance than without, there is a strong financial incentive for the hospital to set charges as high as possible. Since the cost per visit is higher at the smaller hospitals, the charges have to be even higher there, making care even less affordable for patients without insurance.

The Cost of Inpatient Care in Small Rural Hospitals

An emergency department alone is not enough to qualify a facility as a “hospital;” the facility must also offer inpatient care.17 This section will examine the costs involved in delivering inpatient care in small, rural hospitals. The focus here will be solely on the general nursing care and “bed and board” services a patient receives during an inpatient stay, not laboratory tests, imaging studies, therapy, surgery, or other services that may be delivered by other hospital departments during their stay. The costs of delivering those other services will be examined in the next section of this chapter.

As with the ED, hospital cost reports include information on the total cost of operating the inpatient unit, but it is impossible to determine why some units are more expensive than others because there is very little information on the individual components of that cost. It is possible to estimate the level of staffing that a hospital would likely need to provide high-quality inpatient care, but this will depend not only on the number of patients who receive inpatient care, but how sick they are and what kinds of services they will need.

The Different Types of Inpatient Care at Small Rural Hospitals

Acute Inpatients

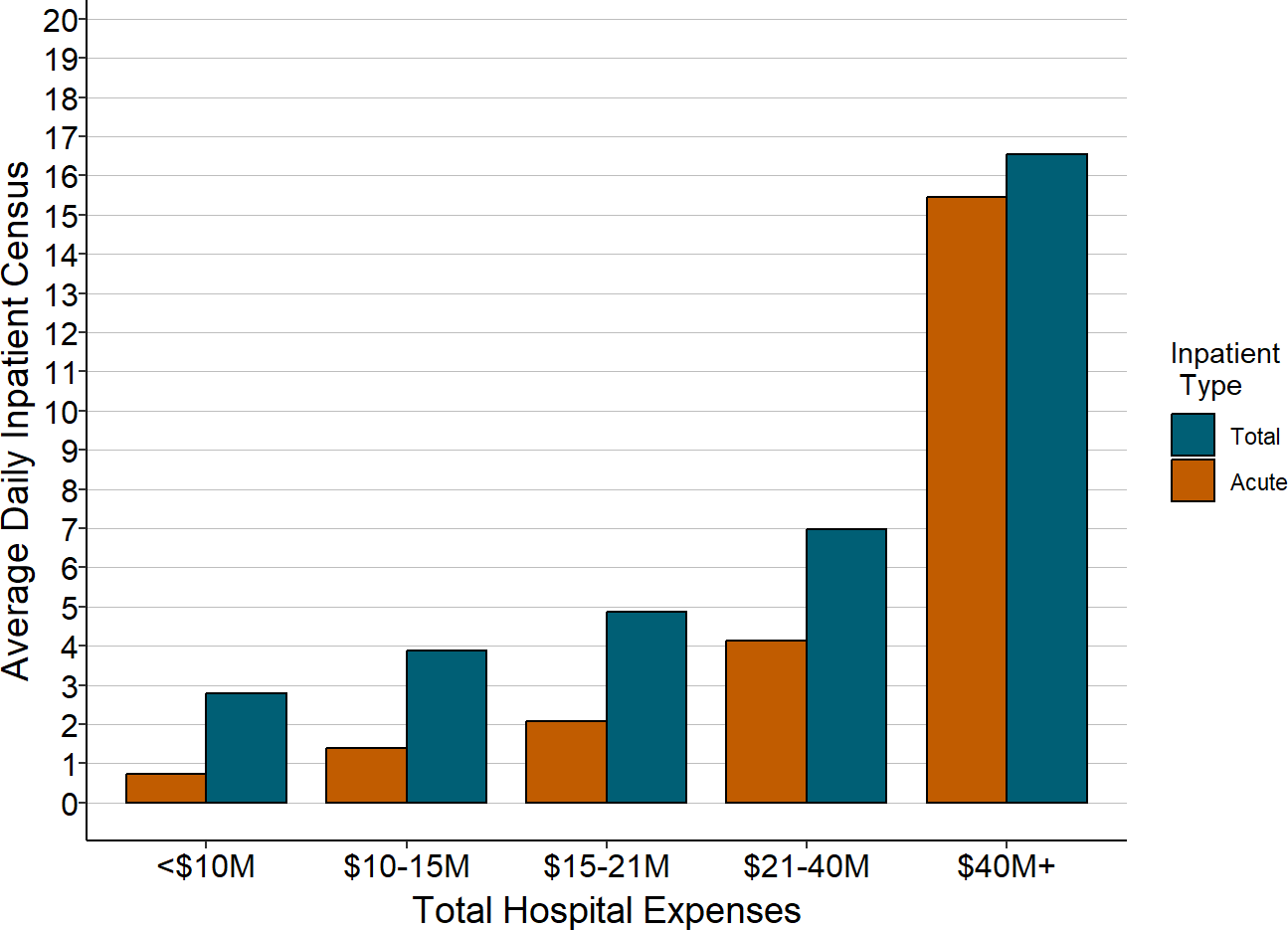

Small rural hospitals have been experiencing the greatest financial challenges. 95% of rural hospitals with less than $45 million in total expenses have fewer than 10 acute inpatients per day, and the majority have fewer than 3 acute inpatients per day on average.

Three patients may seem like a very small number, but in order to have an average of 3 acute patients in the hospital each day, a hospital will generally have to admit over 400 patients during the course of a year. A hospital that has an average of 10 patients receiving acute inpatient care every day will have more than 1,000 admissions per year.

Moreover, annual averages can mask enormous variations from month to month and day to day. Although there are no national data available on the daily numbers of admissions to hospitals, individual small rural hospitals report that the monthly acute inpatient census can vary from 50% to 200% of the annual average. For example, a hospital with an annual average daily acute census of 2 may have an average of 4 patients in the hospital each day during some months, and an average of only 1 patient per day in other months.

Swing Bed Patients

However, small rural hospitals do not use their inpatient beds solely for patients with an acute illness. At almost all small rural hospitals, some or all of the inpatient beds are classified as “swing beds.” A swing bed can be used either for an acute patient (i.e., a patient who is sick enough to require admission to a hospital for treatment or observation), or for a non-acute patient who needs daily skilled nursing care. Swing beds allow rural hospitals to provide two types of services:

- Post-Acute Rehabilitation Services. Many patients cannot return home immediately after discharge from a hospital and need a period of rehabilitation that may last several days or several weeks. Some of the patients receiving post-acute care in rural hospital swing beds are the same individuals who just completed an inpatient stay at the same hospital, but many are patients who received surgery or medical treatment at a hospital in a larger community and then return to the rural hospital to receive rehabilitation care closer to home.

- Long-Term Nursing Care. Three-fourths of small rural hospitals also have long-term nursing patients in their swing beds. These are patients who have medical conditions or physical limitations that require a level of nursing care and personal care that they cannot receive at home.

In larger communities, these types of services are generally provided by Skilled Nursing Facilities (SNFs), but many rural communities are too small to support a separate SNF, particularly in states with low Medicaid payments for long-term nursing care, and the only way residents of the community can receive these services locally is if the hospital provides them through swing beds.

A Rural Hospital’s Total Inpatient Census is Larger Than Its Acute Census

Because a rural hospital’s inpatient unit(s) have both acute patients and swing bed patients, the total inpatient census in the hospital will generally be larger than its acute census, and often significantly larger. The total number of inpatients in the smallest hospitals is 2-3 times as large as what the acute census would suggest.

Figure 17

Average Daily Acute Census

and Total Inpatient Census

in Rural Hospitals

Average daily census and total expense is the median for the most recent three years available, excluding 2020. Acute includes both acute inpatient and observation stays. Total includes acute and swing bed patients.

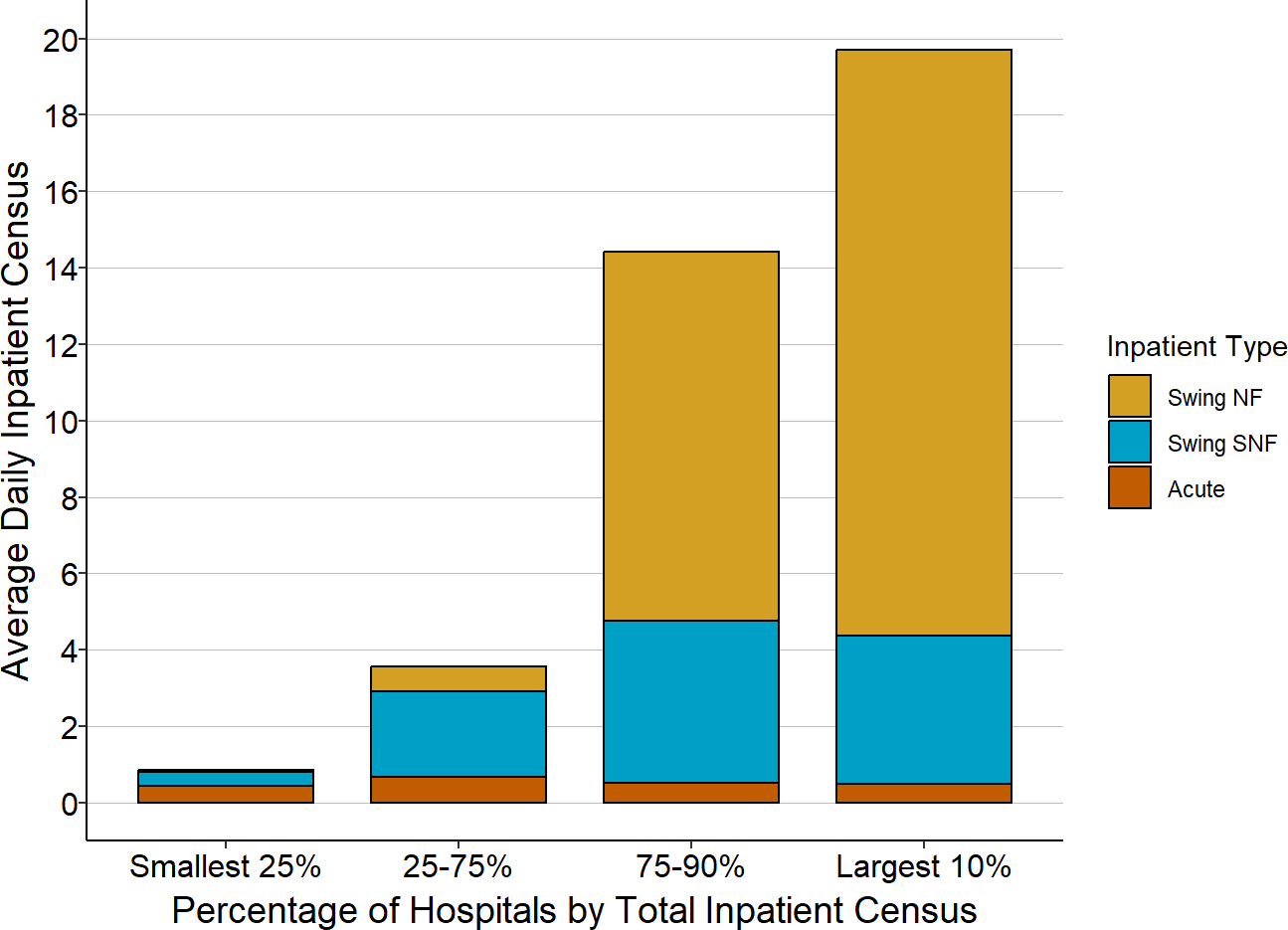

Most rural hospitals use swing beds primarily for post-acute rehabilitation services, and they have at most one or two long-term nursing patients on any given day. Rural hospitals are not restricted to providing rehabilitation services to patients from the local community, so some hospitals with very small numbers of acute patients will have patients from a broader geographic area in their swing beds. The majority of hospitals with an average of less than 1 acute inpatient per day have a much higher total census due to patients in swing beds who are receiving short-term rehabilitation.

In a subset of hospitals, primarily those located in small isolated communities, the majority of patients in the hospital’s inpatient beds are long-term nursing care patients. 5% of small rural hospitals have an average of more than 6 long-term nursing care patients in their inpatient swing bed unit, and 2% have more than 15. In fact, some of the rural hospitals with the smallest number of acute inpatients have more total patients in their inpatient unit on any given day than many larger hospitals do because of the large number of nursing care patients in their swing beds. Among hospitals with less than 1 acute patient per day on average, the largest 10% of the hospitals have an average of more than 16 patients in total in their inpatient units, and the majority of those patients are receiving long-term nursing care.

Figure 18

Types of Inpatients in Rural Hospitals

With Very Small Acute Census

“Swing NF” is patients receiving long-term nursing care in hospital swing beds. “Swing SNF” is patients receiving short-term nursing care and rehabilitation in swing beds. Numbers shown are only for rural hospitals with an average of less than one acute inpatient or observation patient per day in the most recent three years available (excluding 2020).

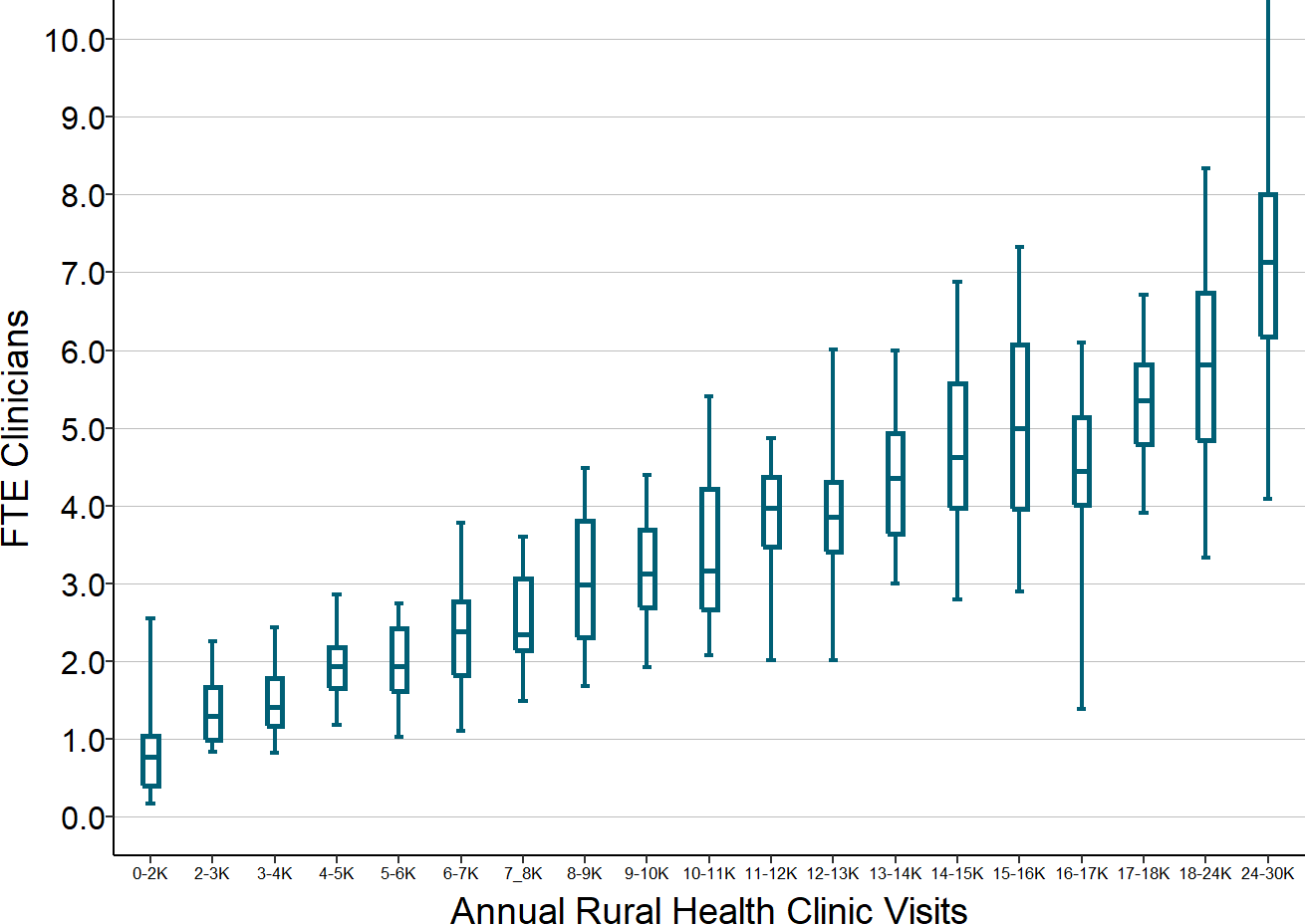

The Cost of Delivering Inpatient Care in Small Rural Hospitals

Most patients who are admitted to small rural hospitals are there for treatment of a common acute medical condition (e.g., pneumonia or cellulitis) or an exacerbation of a chronic disease (such as COPD or heart failure), not for treatment of complex conditions or to receive invasive procedures. (Even if a small rural hospital delivers babies or performs orthopedic procedures, maternity care and surgical cases will generally represent a small fraction of the total acute inpatients.) The patients who are admitted may be too sick to safely return home immediately after they are diagnosed and treated in the emergency department, or they may need a type of treatment that they cannot receive at home, such as intravenous fluids or antibiotics. It is a significant advantage for a patient to be able to receive that kind of care in their own community rather than having to be transported to a hospital in a distant community, but this is only feasible if the hospital can financially sustain an inpatient.

The Cost of Delivering Inpatient Care to a Small Number of Acute Patients

The very smallest hospitals (those with total annual expenses under $10 million) have a median total daily census of 3 in their inpatient unit; the majority of these patients will generally be acute inpatients, with the rest receiving SNF-level rehabilitative care or possibly long-term care in swing beds.

In order to staff such a unit safely, the hospital will likely want to have two nurses on duty during each 12-hour shift. This might seem like a very high nurse:patient ratio to those familiar with staffing patterns for medical inpatient units, where the staffing ratios would be more like 1 nurse for every 5-7 patients. However, there are several reasons why the staffing ratio has to be higher in a small rural hospital:

- Variability in Patient Census. The fact that the average census is 3 does not mean that the census is 3 every day. The daily census can vary significantly because of the inherently random nature of when patients get sick and need to be admitted to the hospital, so on any given day, the number of patients receiving inpatient care could be twice as high or more. One analysis estimated that a hospital with an average daily census of 5 or less would need to staff for twice as many patients in order to have even a 95% assurance of adequate staffing during peak times.18

- Variability in Nursing Time Per Patient. Even if there are only two acute patients on the unit during the day, both patients could need hands-on nursing care at the exact same time, making it unsafe to have only one nurse available. Similarly, if a nurse on duty were to be injured or become ill, it would be unsafe if there were no backup nurse available. In a larger hospital, a nurse from another inpatient unit could be called on to help in such a situation, but in a small rural hospital, there is no “other unit.” In fact, because the nurses on the inpatient unit may be the only nurses in the hospital, they may be called on to help with peak demand in the ED or if someone experiences a medical problem while visiting another outpatient department, and so two nurses will be needed in order to provide that capacity.

- Multiple Nursing Tasks Per Patient. In contrast to a larger hospital, there is no separate set of nurses responsible for admitting or discharging patients; the nurses on the inpatient unit will need to perform these tasks as well as direct patient care. Because the average length of stay is only 2-3 days and some patients will only be in the hospital for a day, there will likely be 1-2 admissions or discharges every day19 and it would be impossible for a single nurse to do this as well as provide constant supervision of the patients who have been admitted.

In order to have two nurses on duty at all times during the day, every day of the year, the hospital will have to employ more than two nurses in total. As discussed in the previous section with respect to the Emergency Department, in order to have a nurse present around the clock, a hospital will have to employ 4-5 nurses in total. So, on an inpatient unit, in order to have two nurses for each of the two 12-hour shifts each day, the hospital will need to employ as many as 10 nurses in total. Because of the cost and difficulty of attracting and retaining Registered Nurses (RNs), many hospitals will likely use a combination of an RN and a Licensed Practical Nurse (LPN) on some or all shifts.20

If the hospital pays $38/hour for RNs, $26/hour for LPNs, and provides benefits equivalent to 20% of wages, it would need to spend over $800,000 on nursing staff for an inpatient unit with this many patients.

In addition to the nurses, a hospital will also be likely to employ additional staff to directly support the inpatient unit, such as:

- A Nursing Assistant on each shift, who could carry out a variety of patient care duties to enable the nurses to focus on tasks requiring nursing skills.

- A Unit Secretary/Coordinator, at least on the day shift, to handle calls, visitors, paperwork, and other tasks.

Figure 19

Cost of the Inpatient Unit

at a Hypothetical Small Rural Hospital

Daily Inpatient Census: 3

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Unit Cost | FTEs | Cost | |

| RN | $38/hour | 5.0 | $395,000 |

| LPN | $26/hour | 5.0 | $270,000 |

| Nursing Assistant | $15/hour | 5.0 | $156,000 |

| Other Staff | $16/hour | 2.5 | $83,000 |

| Total Wages | $905,000 | ||

| Benefits | 20% of Wages | $181,000 | |

| Other Direct | $130,000 | ||

| Total Direct | $1,216,000 | ||

| Indirect Cost | 100% of Direct | $1,216,000 | |

| Total Cost | $2,432,000 | ||

Most of the direct costs of the inpatient unit will be associated with the nurses and other staff. As with the Emergency Department, the costs of any medications and other supplies that are billed separately will ordinarily be assigned to a separate hospital cost center (these costs will be discussed separately in the next section), so non-personnel costs for the inpatient unit will generally be a small proportion of the total direct cost.

However, the inpatient unit will depend on the hospital providing space and utilities, maintenance, housekeeping, dietary services, laundry, billing for patient visits, payroll and benefits for staff, medical records, etc., and a portion of the hospital’s costs for those activities must be allocated to the inpatient unit to properly represent the total cost of inpatient care. Typically, the indirect costs will increase the total cost of an inpatient unit by 100% beyond the personnel and other direct costs discussed above.21

Figure 19 shows that the total cost could be expected to be about $2.4 million for an inpatient unit with this level of staffing at a hypothetical hospital.

The Cost of Inpatient Care for a Smaller Number of Acute Patients

A hospital will still likely want a similar level of nurses even if the average daily census is lower than 3. Even if the hospital has only 1 or 2 patients per day on average instead of 3, the random nature of admissions and the seasonality in admission rates means that it will still have 2, 3, or even more patients on some days and it needs to be prepared for that. Moreover, many hospitals with small numbers of admissions also have small emergency departments that rely on the nurses on the inpatient unit to help with ED visits as well as provide care on the inpatient unit, so it would be unsafe to have only one nurse available. A hospital would be less likely to have a nursing assistant or other staff if the total census was very low, but very few hospitals have a total daily census below 2.

The Cost of Inpatient Care for a Larger Number of Acute Patients

Because the nursing staffing levels described above are designed to handle variations in the number of patients, there will be no need to change the staffing levels if the average daily census is slightly higher than 3. If a hospital has a significantly larger number of patients every day, it will need to have additional nurses and potentially other staff on the unit, but the number of staff will not be directly proportional to the number of patients. For example:

- If the average daily census is closer to 6 than to 3, the hospital will likely want 3 nurses on duty on some or all shifts instead of 2 nurses, particularly if a high proportion of the patients are acute admissions rather than patients receiving rehabilitation or long-term care in swing beds.

- If the average daily census is closer to 9 and most of the patients are receiving acute care, the hospital will likely want another nurse on the day shift because of the higher workload during the day than at night.

- If there are an average of 14 patients on the unit, most of whom are acute patients, the inpatient unit begins to look more like an inpatient unit at a larger hospital, except that the staffing will still need to be higher than at a larger hospital because there are no other units at the small hospital to provide backup support and no other nurses to perform admission and discharge tasks, so the hospital may have 4 nurses on every shift.

The table below shows estimated costs for hypothetical hospitals with these levels of staffing, wages, and benefits for the different levels of inpatient census.

Figure 20

Cost of Hypothethical Inpatient Units

With Different Numbers of Patients

| Daily Inpatient Census | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute Census | 2.0 | 4.0 | 6.0 | 9.3 |

| Swing SNF Census | 1.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 4.7 |

| Swing NF Census | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Total Inpatients | 3.0 | 6.0 | 9.0 | 14.0 |

| Staffing (FTEs) | ||||

| RN | 5.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 12.0 |

| LPN | 5.0 | 5.0 | 7.5 | 7.5 |

| Nursing Assistant | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 7.5 |

| Other Staff | 2.5 | 2.5 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| Cost | ||||

| RN | $395,000 | $790,000 | $790,000 | $948,000 |

| LPN | $270,000 | $270,000 | $406,000 | $406,000 |

| Nursing Assistant | $156,000 | $156,000 | $156,000 | $234,000 |

| Other Staff | $83,000 | $83,000 | $166,000 | $166,000 |

| Total Wages | $905,000 | $1,300,000 | $1,518,000 | $1,754,000 |

| Benefits | $181,000 | $260,000 | $304,000 | $351,000 |

| Other Direct | $130,000 | $135,000 | $140,000 | $150,000 |

| Total Direct | $1,216,000 | $1,695,000 | $1,962,000 | $2,255,000 |

| Indirect Cost | $1,216,000 | $1,695,000 | $1,962,000 | $2,255,000 |

| Total Cost | $2,432,000 | $3,390,000 | $3,924,000 | $4,511,000 |

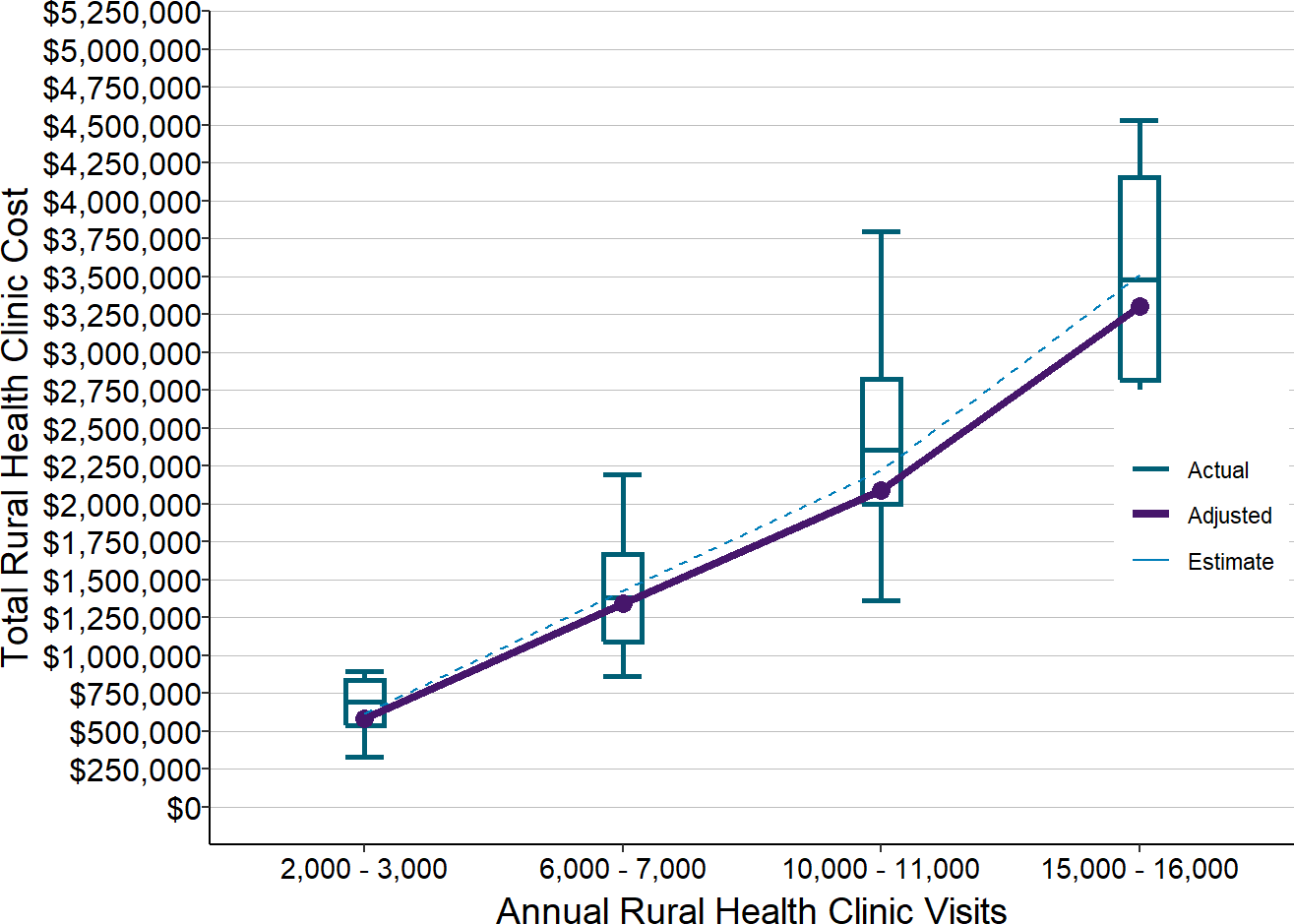

Actual vs. Estimated Costs

The estimates shown for the hypothetical hospitals in Figure 20 do not represent what any individual hospital inpatient unit should cost or what the differences in costs between inpatient units of different sizes should be. For example:

- the exact number and types of nurses the hospital employs, and the amounts it pays those nurses, will depend heavily on the hospital’s ability to attract and retain nurses in the community. Hospitals in isolated areas are less likely to have a pool of nurses in the community who are able and willing to work part-time, so a hospital in one of these areas may need to employ more nurses on a full-time basis in order to ensure that it will have adequate coverage for all shifts.

- a hospital in a more isolated area may also need to pay more to hire nurses than a hospital in an area that is closer to an urban center.

- if a nurse retires or resigns, the hospital will likely have to hire a “traveling” nurse to temporarily fill the vacancy, and this will increase the hospital’s personnel costs in the year in which the vacancy occurs.

- if outpatient surgical procedures are performed at a small hospital, there will likely not be enough procedures to support a separate nursing staff for that, and so the nurses on the inpatient unit will spend a portion of their time assisting with the procedures and the patients’ recovery. The portion of the inpatient nurses’ time that is assigned to the surgical cost center will reduce the cost of the inpatient unit, but the hospital may also need a higher number of nurses on the days when surgical procedures are performed than if the nurses were only caring for inpatients.

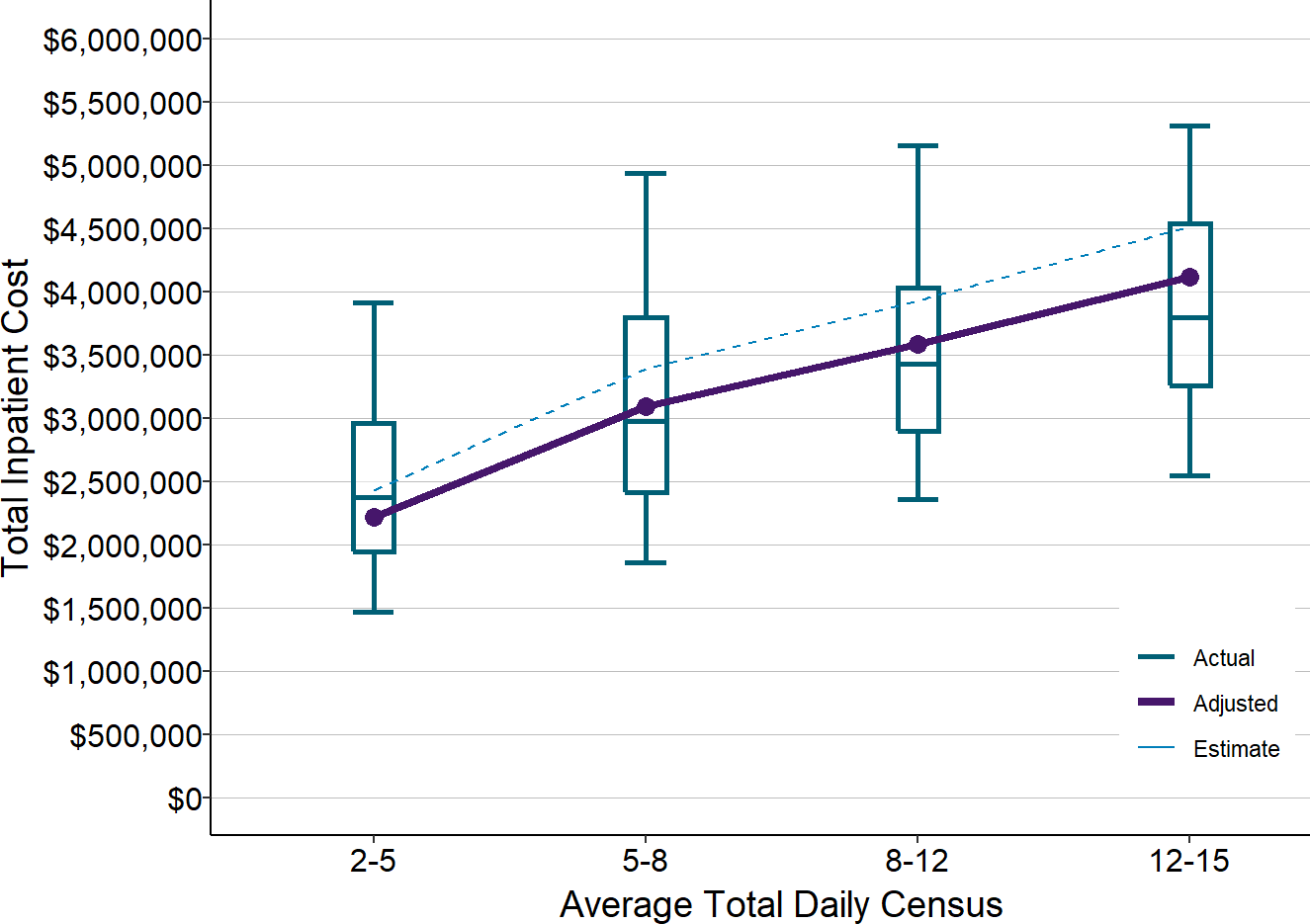

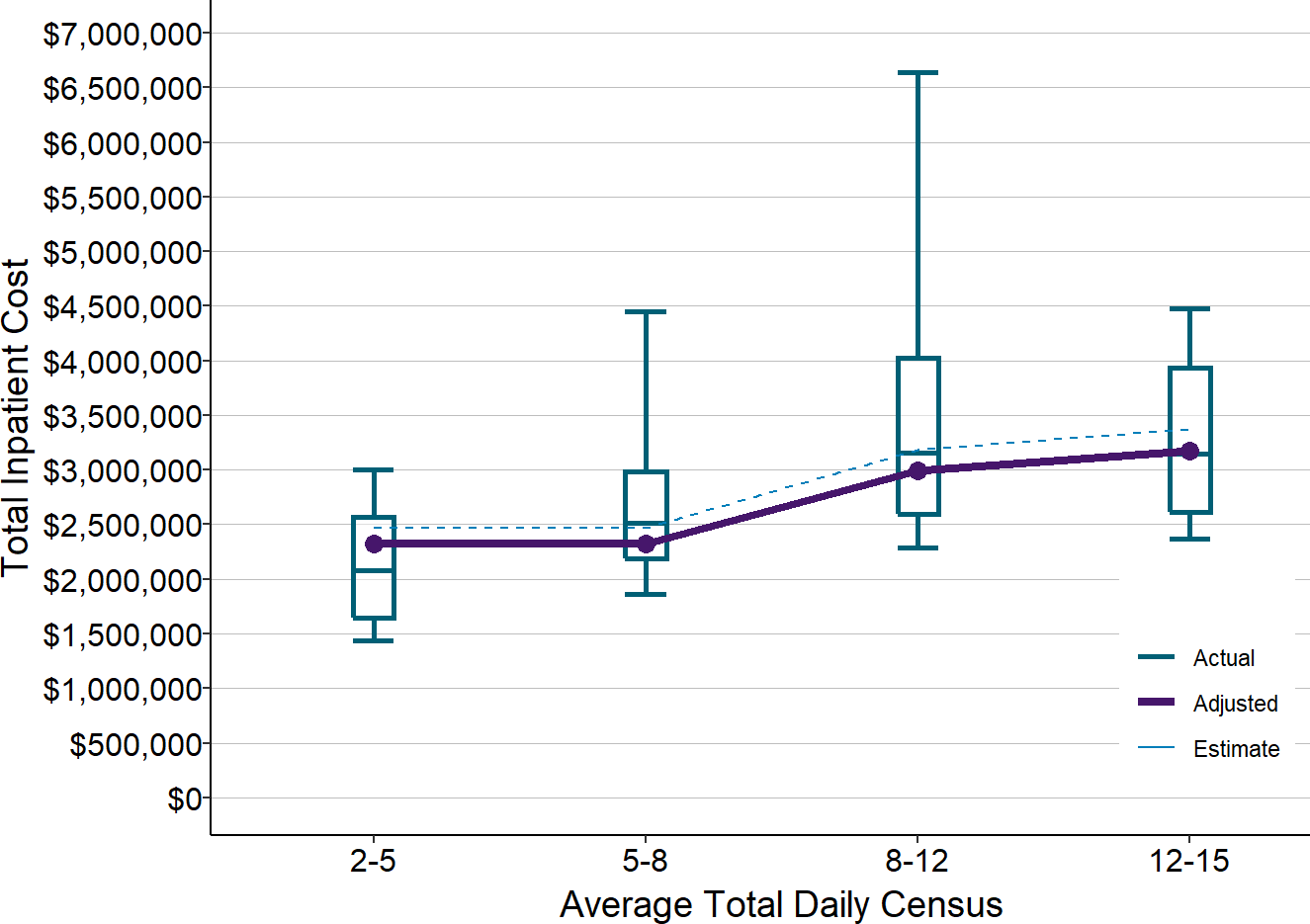

Nonetheless, the cost models provide useful insights into what it can cost to operate inpatient units at small rural hospitals and the potential magnitude of differences based on size. As shown below, the estimated costs in Figure 20 are similar to the median actual costs for rural hospitals, but there is also considerable variation for individual hospitals.22

Figure 21

Actual vs Estimated Costs of Inpatient Units

at Small Rural Hospitals

Actual amounts are from 2017-19 at rural hospitals with less than $30 million in total expenses. Estimates (dotted line) are from Figure 20. Adjusted values (solid line) are the estimated values reduced to reflect inflation between 2018 and 2020.

The Cost of Inpatient Care with Large Numbers of Swing Bed Patients

As discussed earlier, some small rural hospitals have a small number of patients receiving acute care but a large number of long-term nursing care patients in swing beds. These hospitals may have the same total number of patients in inpatient beds each day as other hospitals, but the average acuity level of the patients will be lower, so the number and types of staff needed will likely be somewhat different. For example, although the hospital will still need to have at least 2 nurses, including one RN, to handle the work associated with the acute patients, they may have more LPNs and more nursing assistants for the patients in swing beds than if those patients were acute patients. The following table shows what the costs might look like with hypothetical levels of staffing and wages for different numbers of patients.

Figure 22

Cost of Hypothetical Inpatient Units

With Different Types of Patients

| Daily Inpatient Census | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute Census | 0.5 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 2.3 |

| Swing SNF Census | 1.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 4.7 |

| Swing NF Census | 1.5 | 3.0 | 4.5 | 7.0 |

| Total Inpatients | 3.0 | 6.0 | 9.0 | 14.0 |

| Staffing (FTEs) | ||||

| RN | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| LPN | 5.0 | 5.0 | 7.5 | 7.5 |

| Nursing Assistant | 5.0 | 5.0 | 7.5 | 10.0 |

| Other Staff | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| Cost | ||||

| RN | $395,000 | $395,000 | $395,000 | $395,000 |

| LPN | $270,000 | $270,000 | $406,000 | $406,000 |

| Nursing Assistant | $156,000 | $156,000 | $234,000 | $312,000 |

| Other Staff | $0 | $0 | $83,000 | $83,000 |

| Total Wages | $822,000 | $822,000 | $1,118,000 | $1,196,000 |

| Benefits | $164,000 | $164,000 | $224,000 | $239,000 |

| Other Direct | $250,000 | $250,000 | $250,000 | $250,000 |

| Total Direct | $1,236,000 | $1,236,000 | $1,592,000 | $1,685,000 |

| Indirect Cost | $1,236,000 | $1,236,000 | $1,592,000 | $1,685,000 |

| Total Cost | $2,472,000 | $2,472,000 | $3,183,000 | $3,370,000 |

Here again, the exact number and types of nurses and other staff that a hospital employs, and the amounts that it pays those employees, will depend heavily on the ability of the hospital to attract and retain nurses and other staff in the community. As shown in the figure below, the costs at the hypothetical hospitals above are similar to the median costs at actual hospitals with those numbers and types of patients, but there is considerable variation among individual hospitals.

Figure 23

Actual vs. Estimated Costs of Inpatient Units

at Small Rural Hospitals with Many Swing Bed Patients

Actual amounts are from 2017-19 at rural hospitals with less than $30 million in total expenses. Estimates (dotted line) are from Figure 22. Adjusted values (solid line) are the estimated values reduced to reflect inflation between 2018 and 2020.

This shows that another reason for variation in inpatient costs across different hospitals is the difference in the types of patients at those hospitals. Even if two hospitals have the same average number of acute inpatients, the cost of the inpatient unit will be higher if it also has a large number of patients in swing beds. Conversely, if two hospitals have the same number of total inpatients, the cost of one inpatient unit will be higher if a higher proportion of the patients are acute admissions.

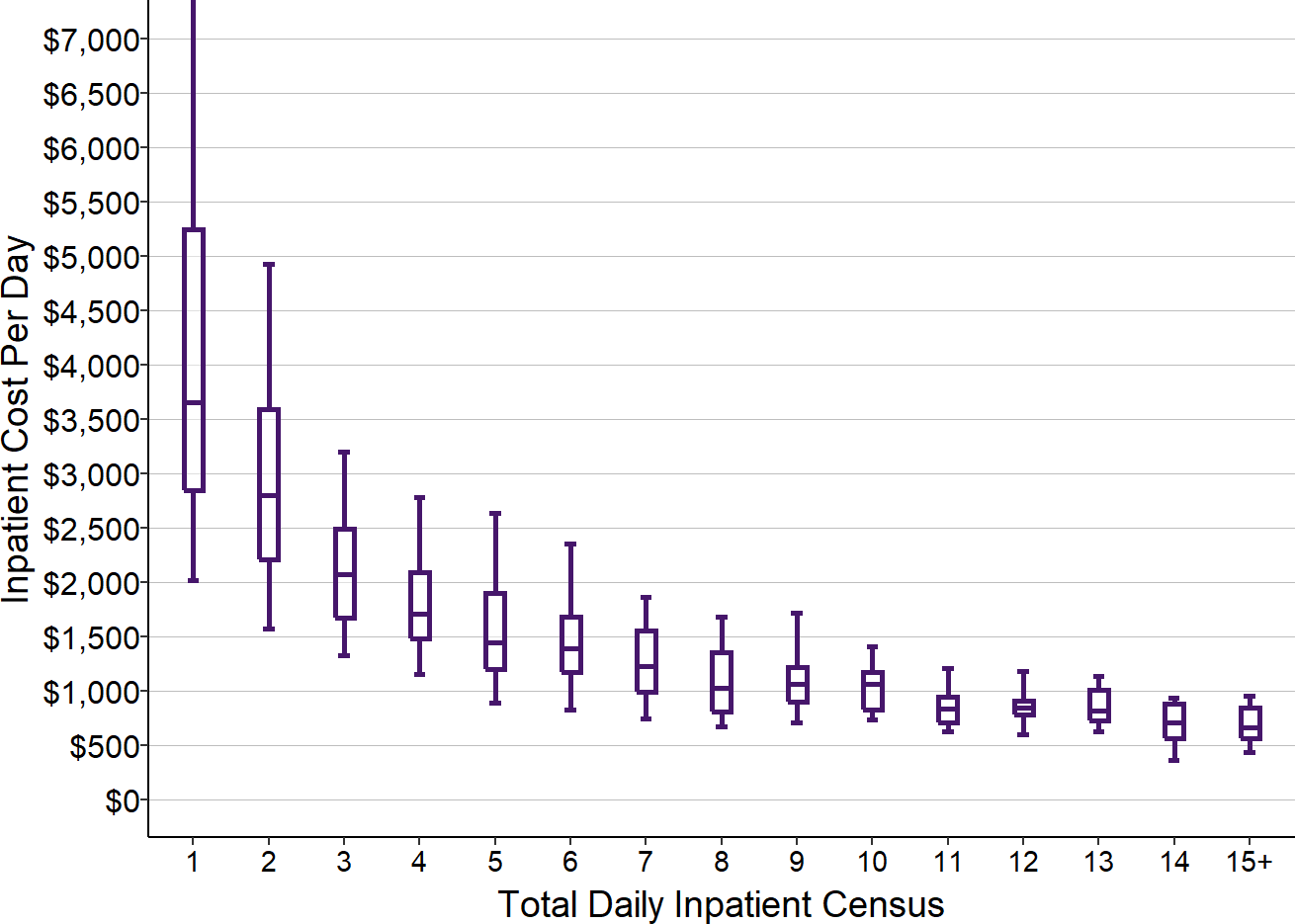

Differences in the Average Cost Per Patient Between Different Hospitals

Although the total cost of operating an inpatient unit will generally be higher for inpatient units with more patients, the analysis above shows that the differences in costs will not be proportional to the differences in the number of patients. The estimated cost in Figure 20 for a hospital with an average daily census of 6 is only 39% higher than the estimated cost for a hospital with an average census of 3, even though there are twice as many patients on an average day. On the other hand, the total cost may not differ at all for hospitals that have only small differences in the number of patients; in the example, the same staffing would likely be appropriate whether the average daily census is 2.5, 3.0, or 3.5, and so the cost could be the same even though the number of patients differs by as much as 33%.

This means that the average cost per patient day will be significantly lower at hospitals with higher numbers of patients. As shown below, the average cost per patient day at the hypothetical hospital with an average daily census of 3 is $2,221, while the average cost per patient day for the hypothetical hospital with an ADC of 6 is $1,548, i.e., 30% less. At the high end of the range, the cost per day at the hospital with an average of 14 patients per day is $883, which is less than half the cost at the hospital with an average of 3 patients.

Figure 24

Differences in the Estimated Cost Per Inpatient Day

at Hospitals with Different Numbers of Patients

| Daily Inpatient Census | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute Census | 2 | 4 | 6 | 9 |

| Swing SNF Census | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| Swing NF Census | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total Inpatients | 3 | 6 | 9 | 14 |

| Cost | ||||

| Total Cost | $2,432,000 | $3,390,000 | $3,924,000 | $4,511,000 |

| Cost Per Service | ||||

| Cost Per Day | $2,221 | $1,548 | $1,195 | $883 |

The figure below shows that the actual cost per day at rural hospitals follows this pattern. The median cost per day at hospitals with small numbers of inpatients is double, triple, or even quadruple the median cost per day at hospitals with larger numbers of patients.

Figure 25

Cost Per Inpatient Day

at Small Rural Hospitals

Values are the medians for 2017-19 at rural hospitals <$30M total expenses where long-term nursing care patients in swing beds represented less than 5% of all inpatient days.

The fact that some hospitals have higher costs per day than hospitals with a smaller census does not necessarily represent inefficiency; in some cases, it is simply due to variations from community to community in the ability to attract and retain nurses and other staff.

The average cost per patient at a hospital will depend not only on the average cost per patient day, but also the average length of stay for the patients. The average length of stay for acute inpatients at small rural hospitals is about 3 days, so the total bed and board cost of an inpatient stay will generally be hundreds or thousands of dollars higher at hospitals with fewer patients.23

The Problems Caused by Per Diem and Per Case Payments

Although the cost of operating an inpatient unit is not directly proportional to the number of patients, the hospital’s revenue usually is. Hospitals are generally paid for inpatient care either through a per-diem fee (i.e., a payment for each day that a patient spends in the hospital) or a single case rate (a payment for the entire hospital stay regardless of how long the patient is in the hospital). As a result, when the number of patients admitted to the hospital increases, the hospital’s revenue increases proportionally, and when the number of admissions decreases, so does revenue.24

This approach to payment causes the same kinds of problems for the inpatient services delivered by small rural hospitals that fees for ED visits cause for the emergency department.

Payments for hospitalizations that are adequate for larger hospitals will cause losses at small rural hospitals.

For inpatient units with a total daily census above 9, the median cost per day was under $1,000, so a per diem payment of $1,000 would be sufficient to cover the cost of the nursing care for those patients. However, a $1,000 per diem payment would cause significant losses at hospitals with fewer patients. Those hospitals that have to pay more to attract and retain an adequate number of nurses and other staff will also have greater losses if they are paid the same amount per patient as other hospitals of similar size.

Even if the per-diem or case rate amounts appear adequate to cover the costs of inpatient services when the year begins, if unexpected vacancies occur in the nursing staff that require the hospital to hire temporary nurses, the cost of the inpatient unit will increase and the payments may no longer be adequate.

The adequacy of any payment amount depends on how many patients are actually admitted.

As with visit-based fees in the emergency department, the problem with per diem and per admission payments for inpatient care is not just the amount of payment, but the method of payment. Because revenues change in direct proportion to the number of admissions when admissions increase or decrease, but costs barely change at all, even small changes in the number of patients admitted can result in larger or smaller losses or profits.

Figure 26

Impact of Changes in the Number of Inpatients

on the Cost Per Inpatient Day

| Daily Inpatient Census | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute Census | 3.8 | 4.0 | 4.2 |

| Swing SNF Census | 1.9 | 2.0 | 2.1 |

| Swing NF Census | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Total Inpatients | 5.7 | 6.0 | 6.3 |

| Cost | |||

| Total Cost | $3,390,000 | $3,390,000 | $3,390,000 |

| Cost Per Service | |||

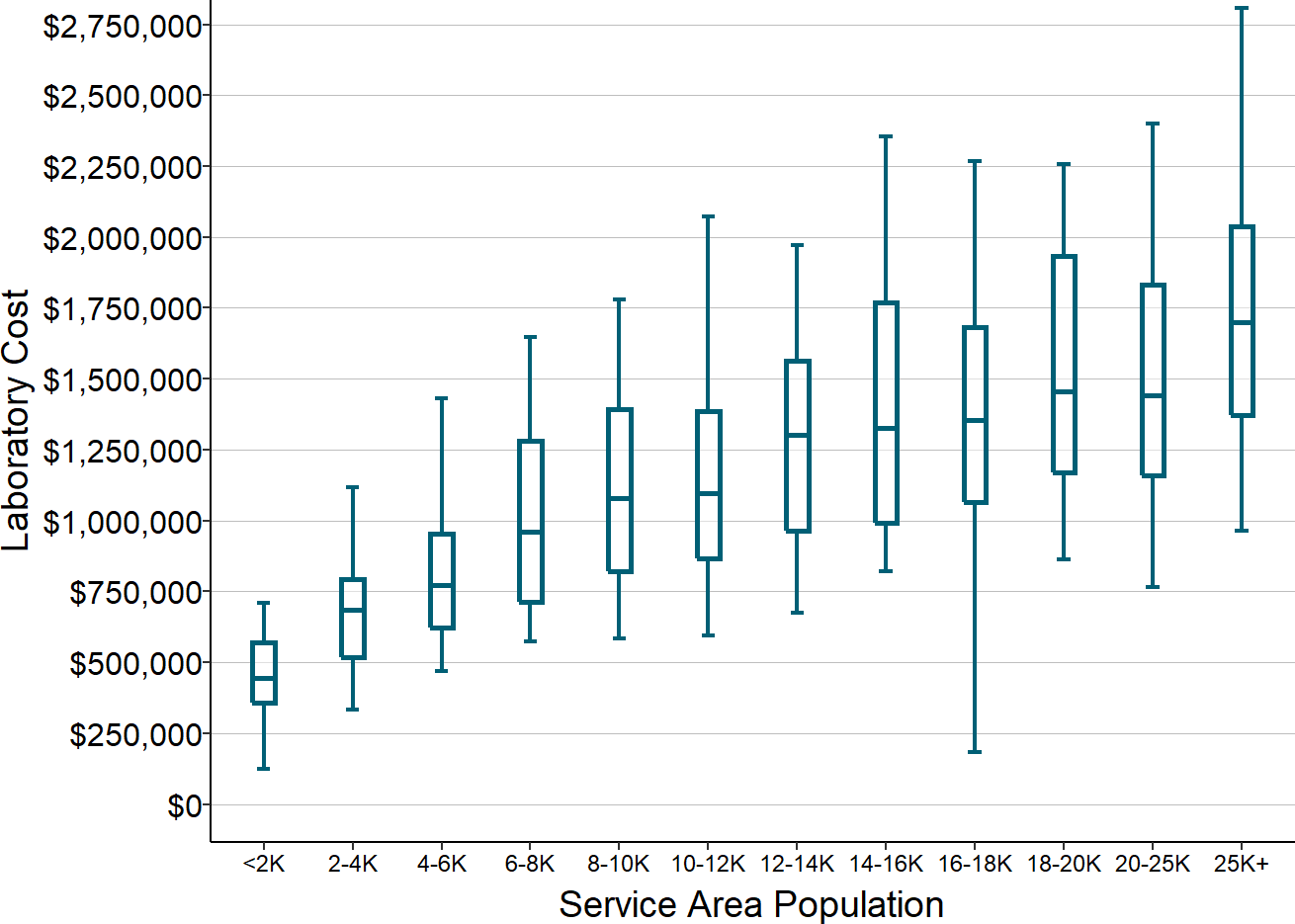

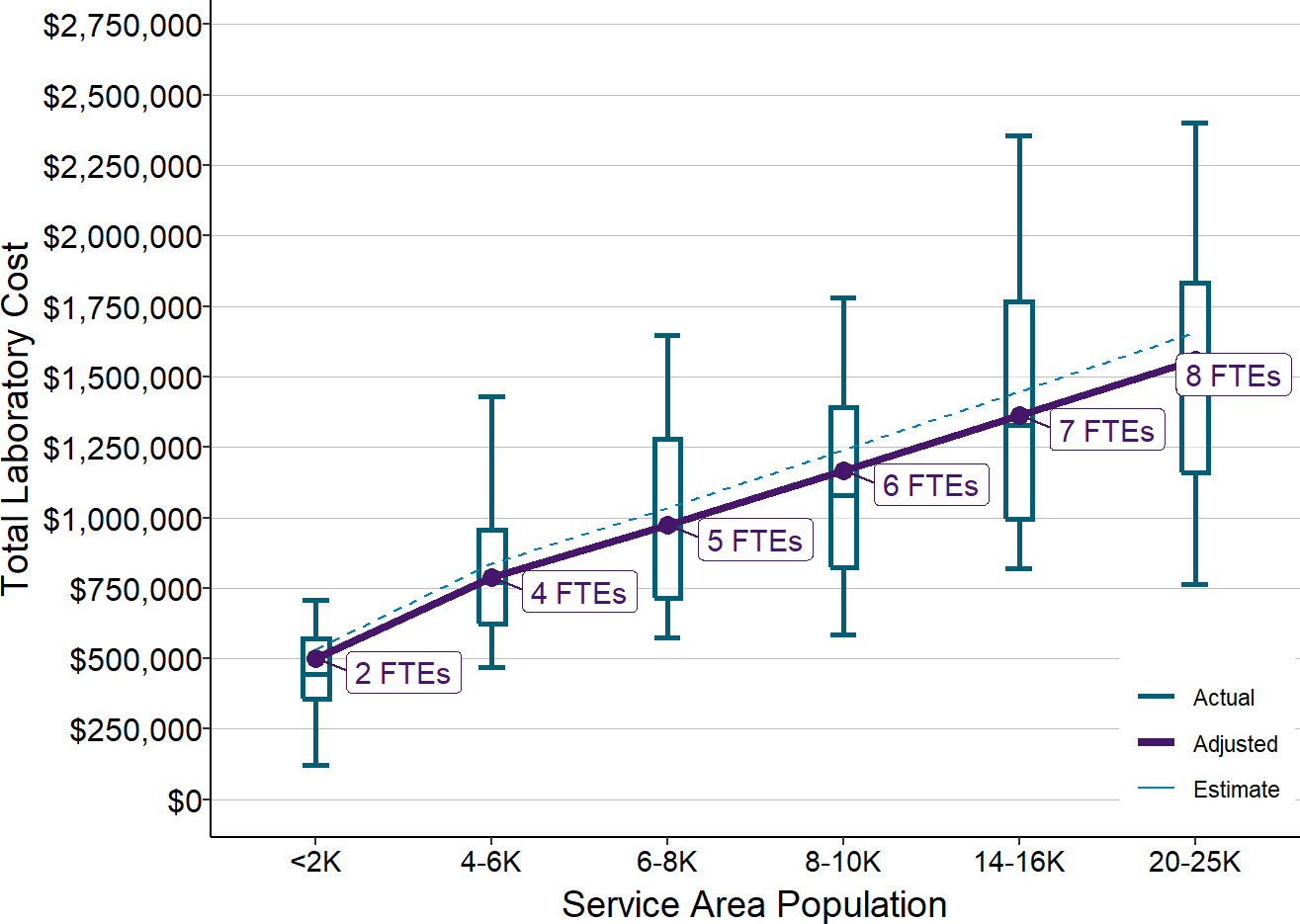

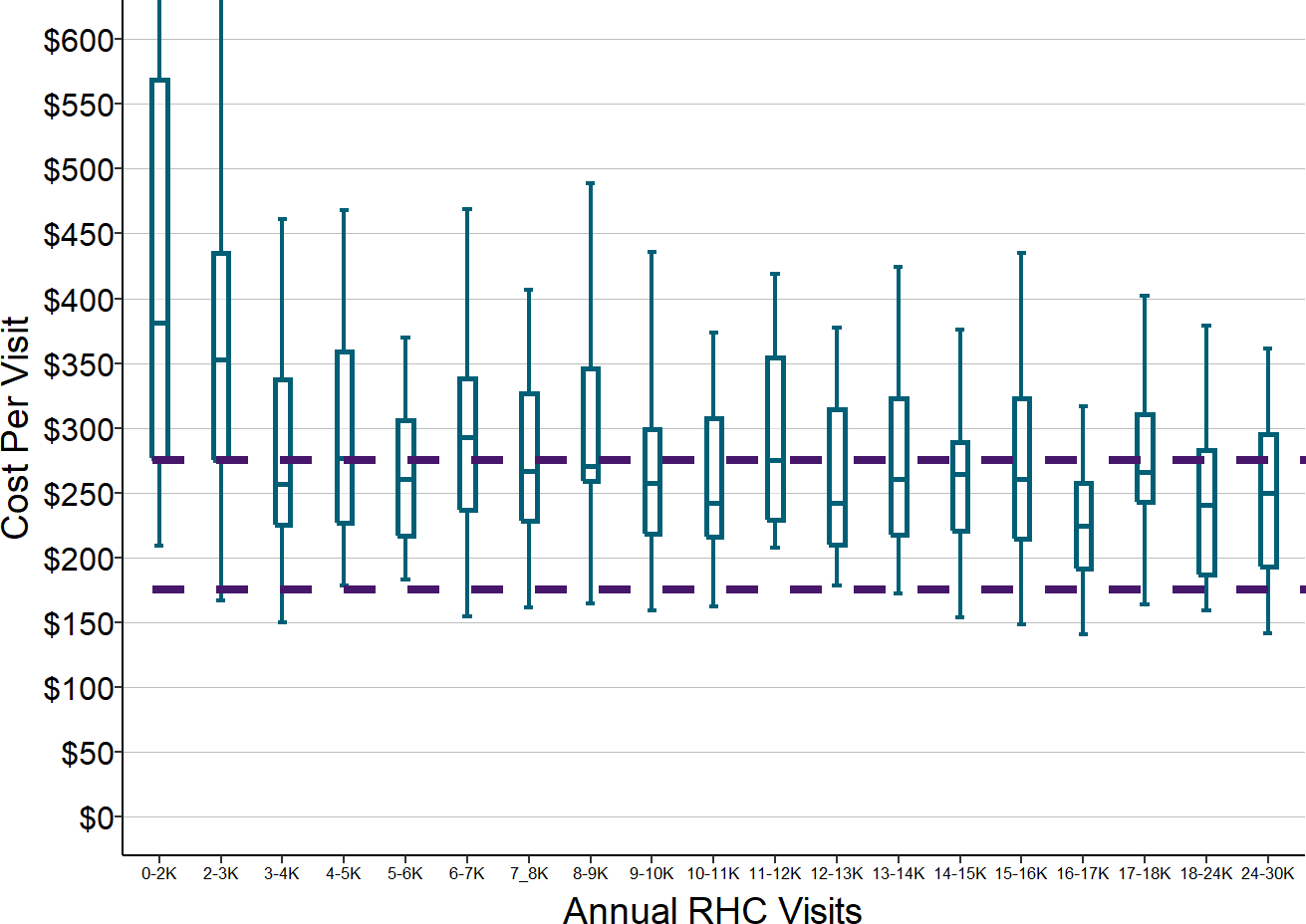

| Cost Per Day | $1,629 | $1,548 | $1,474 |